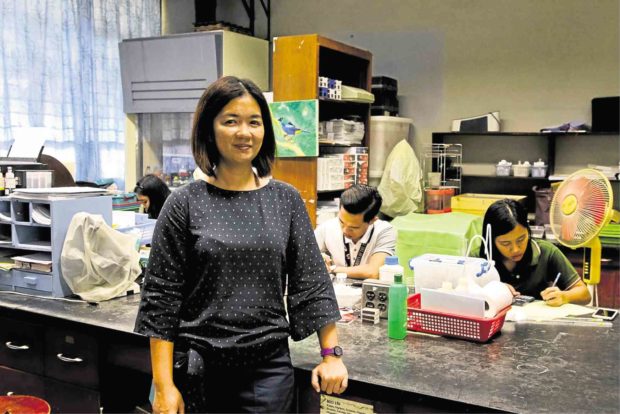

AWARDEE Dr. Aimee Dupo’s “Faces of the Teacher” award recognized her as a “force that shaped a nation.”—CHRIS QUINTANA/ CONTRIBUTOR

LOS BAÑOS, Laguna — Along with their ABCs and nursery rhymes, Dr. Aimee Lynn Barrion Dupo drilled into her two boys, aged 8 and 4, what she considers a basic fact of life — spiders are not insects. As far as the Barrion family is concerned, the arachnids might well be family members.

That her parents are renowned Filipino scientists Dr. Alberto and Dr. Adelina Barrion, whose studies center on spiders, explains why Dupo herself got bitten by the same bug. Alberto, 63, is a retired taxonomist of the International Rice Research Institute (Irri) whose studies focused on spiders in ricelands. Wife Adelina, a former faculty member of the University of the Philippines Los Baños (UPLB), specialized in spider genetics. Because there is no specific course on arachnology, the Barrions resorted to “self study” on spider taxonomy using their training in entomology.

“Spiders have really become a family affair,” Dupo said.

But aside from an interest in spiders, Dupo’s parents bequeathed her something else that came with their being achievers: a lot of pressure.

“It’s either people expected (me) to be as good as (my) parents, or they’d say (I) only achieved this much because of (my) parents. It’s like ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t,’” she said.

Still, the 39-year-old entomologist proved once again that she is more than her parents’ daughter.

Prestigious award

On Sept. 1, Dupo, a UPLB professor and curator of the UPLB Museum of Natural History, was among the awardees of “Faces of the Teacher,” a prestigious award given by Bato Balani Foundation Inc. and Diwa Learning Systems Inc. to Filipino teachers for “becoming a force that shapes the nation.”

The second of five children, and the only one who followed their parents’ career path, Dupo recalled tagging along with her father to the Irri and “playing with forceps and microscopes in the lab.”

In college at UPLB, Dupo took up agriculture and majored in entomology. Her thesis was about derby spiders or spiders used in spider fights or spider wrestling, a pastime and form of gambling in the Philippines. She studied the fighting behavior of these “eensy weensy” creatures, trying to decipher if they are fiercer when famished or when they had just hatched their eggs.

“After classes, I’d go home to watch spiders fight each other,” she recounted, adding that unlike in Japan where “spiders do not fight to the death,” here, “once the fighter is maimed, it is fed to the other spiders.”

Her parents apparently took an inordinate interest in her undergraduate thesis as well. It was like having two more thesis advisers at home, Dupo said. “There was no avoiding it. From breakfast to dinner, (my parents) talked about (my) research,” she recalled.

“WE ARE FAMILY.” Dr. Aimee Dupo shows a preserved spider specimen inside a vial. —KIMMY BARAOIDAN

‘Underdogs’

After graduation, Dupo decided to set aside her spider research to focus on moths and other arthropods. Like spiders, moths are considered the “underdogs” in entomology, with only a handful of studies done on them. Most people think of moths as pests, she said.

Her plans changed when her mother passed away in 2010, and so did the elder woman’s idea of a pictorial guide on Philippine spiders, a reference material that can be used by younger scientists interested in studying spiders.

It set her father thinking that “he might not live long enough and that we should start working on the pictorial guide,” she said, adding that she plans to release the pictorial guide in time for her birthday in March.

The father-daughter tandem is currently the only Filipino scientists studying spiders. So far, they have named and provided information in the scientific database of 45 spider species from China and 27 species of rice black bugs.

Dupo herself has so far described five species of derby spiders that she named after her father and siblings.

“In the Philippines, we have so far documented about 532 to 534 spider species, most of them from the rice-agro system. Those from the forest system we have only come to know recently. There are too many of them (to be discovered) and that number can double in a few years’ time,” she said.

Hopefully, her recent award would encourage more people to study spiders and other insects, Dupo said.

“Before we can protect any place, we have to know what’s inside it. For instance, we know that spiders are predators, but are they active hunters? Are they day hunters? Who feeds on them?” she asked.

‘Jigsaw puzzle’

For Dupo, studying biodiversity is like working on a “jigsaw puzzle.”

“There might be irreplaceable relationships (in the ecosystem) that could be gone before we document them. That has always been the battle,” she said.

As a teacher and a scientist, Dupo juggles her time between teaching and studying spiders and moths. She would spend the day collecting spiders and at nightfall, would be catching moths for her research. One of her recent fieldwork was on Mt. Guiting Guiting on Sibuyan Island in Romblon.

“My eldest once told me that he wanted to burn down the forest. That was the time when we had to go on fieldwork almost weekly,” she said.

Eventually, her children got used to her bringing home vials that contained spiders and tarantulas. Even her room at home is filled with cobwebs, she added.

She doesn’t mind, Dupo said. “Those cobwebs, courtesy of the comb-footed spiders — those little creatures we often see at home — trap dirt and dust, making household cleaning easier.”

This eight-legged creature that people often regard with disgust actually have practical uses, she added. For one, those palm-sized spiders hanging around the shower feed on cockroaches.

“So it now becomes a dilemma — are you keeping the spider or the cockroaches?” she asked.