Concert by local artists to raise funds for the medical needs of the folk minstrel beloved by Kapampangans —TONETTE T. OREJAS

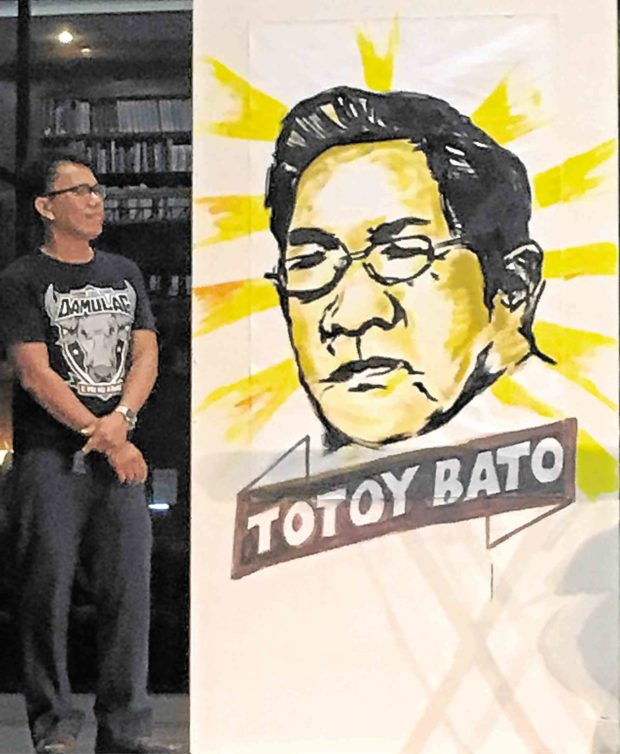

ANGELES CITY — Minus his guitar, 73-year-old Totoy Bato limped into Plaza San Juan of Holy Angel University (HAU) here. His wife, Nena, was by his side.

When the crowd of mostly college students read his name stitched to his old yellow jersey vest, many stood up and gave Totoy (Rodolfo Laxamana in real life) an enthusiastic applause. It was a tribute and fund-raising concert for the “polosador” (folk minstrel) who suffered a stroke months ago.

Back in the 1980s, Totoy’s songs or “polosas” were heard locally or through Betamax recordings in Saudi Arabia. A polosa is composed extemporaneously in metered verses and repetitive chords.

“His brand of Kapampangan poetry and music was the first to be exported,” archivist Francis Musni told the people who gathered for the tribute on July 20.

“When he belts out a song that harks back to the polosas of yore, Totoy doesn’t just sing the lyrics but also speaks the truth, often sugarcoating it with his seeming flippancy and frivolity,” said Alex Castro, a museum curator and writer. “That’s what makes his music so appealing, a spoonful of humor does make the medicine go down.”

Totoy said composing a song required a “quick mind to observe what is happening, to capture the human emotions, and to compose the song in lyrics and tunes.”

No copyrights

He failed to secure copyrights for his works, however. Because his songs reflected the situations and aspirations of his province mates across the globe, these were copied thousands of times without his consent or knowledge.

That was not bad for the Angeles City-born artist whose formal education stopped at Grade 6 due to poverty. He made a living as a gasoline boy and by driving jeepneys and trucks.

Totoy learned to rhyme by listening to poet Jose Gallardo over radio station dzAB. Soon, he was jousting with the late poet Mariang Samat and singing the “bulaklakan” during wakes.

He took the name Totoy Bato after watching film icon Fernando Poe Jr.’s 1979 movie, “Durugin si Totoy Bato.”

“He did not get a platinum record, but he won the hearts of the Kapampangan,” said Robby Tantingco, executive director of HAU Center for Kapampangan Studies. The university conferred a symbolic platinum record to Totoy for promoting Kapampangan language, arts and culture.

YouTube postings

Younger generations, like the Lacap brothers of Masantol town, learned his kind of music through YouTube.

Totoy’s fans posted 24 of his best songs, among them “Ing Bie Sugarul” (The Life of a Gambler), “Lugud ning Indu” (A Mother’s Love), “Sinobra ing Yabang” (So Boastful), “Apat-apulong Aldo” (40 days of flooding in Central Luzon), and “Pinatubo” (Mt. Pinatubo’s 1991 eruptions).

The extent of his creative influence was apparent during the tribute. Local performers Tongits Duo, Dos Palikeros, Bong Manalo and Miss D., John Bendido and Renie “Diwata” Salor all credited their jobs as singers in family reunions, feasts, political rallies, information campaigns, musical concerts or just about any event to Totoy Bato.

Henry Simbulan, the other half of Dos Palikeros, first heard Totoy’s hit, “40 Days,” when he was 10, from a neighbor who played the artist’s cassette tape every morning. “You inspired me,” he told Totoy.

Amid the lavish praises, Simbulan raised his right hand and waved at the crowd as a sign of gratitude. Totoy tried to hold back tears, when young talents from the apl.de.ap Music Studio performed English and Filipino songs translated into Kapampangan.