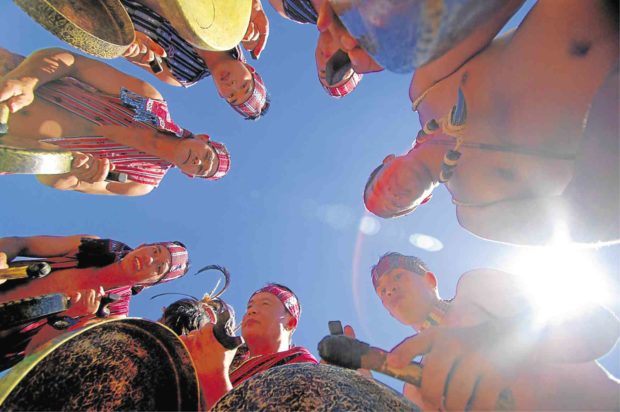

UNITY Playing the gangsa (gong) symbolizes unity among the people of the Cordillera, a region that has struggled to gain autonomy. —RICHARD BALONGLONG

In Barangay Bugnay in Kalinga province stands a new marker that honors leaders who protested the construction of four hydroelectric dams on Chico River during the martial rule of strongman Ferdinand Marcos.

The project would have generated 1,000 megawatts of electricity but would also displace rice terraces and people from 1,400 square kilometers of land where the dams would rise.

On April 24, 1980, soldiers shot and killed one of Bugnay’s most vocal oppositors, Ama Macli-ing Dulag.

Left-leaning groups like the Cordillera Peoples Alliance (CPA) still celebrate Dulag’s martyrdom as Cordillera Day. The marker was put up in this year’s 37th commemoration.

No busts or markers have been put up for the other Cordillera Day, which is celebrated every July 15. On that day in 1987, then President Corazon Aquino issued Executive Order No. 220 forming the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) by drawing together the Region 1 provinces of Benguet, Mountain Province and Abra, and Baguio City, and the Region 2 provinces of Kalinga, Ifugao and Apayao.

Many used to associate CAR with former rebel priest, Conrado Balweg, who broke away from the New People’s Army, formed his own militia, and negotiated a ceasefire with the Aquino administration after the ouster of Marcos in a people’s revolt in 1986.

EO 220 is the outcome of these first talks. It says CAR shall “administer the affairs of government in the region … accelerate the economic and social growth and development of the units of the region; and prepare for the establishment of the autonomous region in the Cordilleras.”

The order also formed the policymaking body, the Cordillera Regional Assembly (CRA), and the implementing agency, the Cordillera Executive Board (CEB).

Balweg had all been forgotten since his assassination in 1999 until early this year when government agencies like the Cordillera Regional Development Council and the National Economic and Development Authority (Neda) cited the slain priest’s role in the campaign for autonomy.

They said Dulag’s martyrdom was as important as the roles of Balweg and Igorot rights groups in establishing CAR because they “all fought to repair what Marcos had tried to destroy.”

Apayao women guide tourists as they explore a river in Luna town. They perform dances, play ethnic instruments and discuss community history with their guests. —EV ESPIRITU

A little history

In 1908, the American colonial government formed the Mountain Province. “With the stroke of a pen, the Igorots were all together in one political unit which, to some, may have looked like a rather formidable ethnic and territorial grouping,” wrote retired anthropology professor Dr. Albert S. Bacdayan in the book, “Towards Understanding Peoples of the Cordillera.”

But in 1966, Congress passed a law dividing Mountain Province into the provinces of Benguet, Mountain Province, Ifugao and Kalinga Apayao.

In 1973, Marcos issued Presidential Decree No. 1 reorganizing the bureaucracy under martial rule, further breaking up the former components of old Mountain Province which were joined to Region 1 (Ilocos Region) and Region 2 (Cagayan Valley).

“The response to this apparently unpopular decision was the repeated call for the creation of a separate region for the mountain provinces,” University of the Philippines professor Athena Lydia Casambre said in her book, “Discourses on Cordillera Autonomy.”

The fight for an Igorot region in the 1980s was spearheaded by the CPA, the Bibak (Benguet-Ifugao-Bontoc-Apayao-Kalinga) professionals, Igorot rights groups and the Church. CPA also advocated the Igorot self-determination and indigenous peoples’ rights.

Igorot Nation

The activism spawned new catchphrases like “Kaigorotan,” the Igorot Nation, and eventually the idea of autonomy for minority groups.

“The lobbying by CPA, taking advantage of the democratic space opened up after the Edsa revolt, was largely responsible for the inclusion of the constitutional provision for autonomous regions in the Cordillera and Muslim Mindanao in the 1987 Constitution,” Casambre said in her book.

But for the last 30 years, EO 220 has been the only law holding CAR together, and, many say, the primary reason for celebrating.

This was because steering CAR toward autonomy had not been an easy ride, said Philip Tinggonong, a retired planning and development officer of Abra and former CEB director.

EV ESPIRITU

Almost immediately after CAR was born, its thrust had been to draw up the law creating the Autonomous Region of the Cordillera (ARC), but the region’s voters rejected two organic laws signed by Aquino and former President Fidel Ramos.

The rejection of the first law, Republic Act (RA) No. 6766, almost led to another breakup of the mountain provinces, when only Ifugao voted in favor of autonomy.

Regional officials were told to dismantle CAR and prepare for an ARC until the Supreme Court ruled that Ifugao alone could not serve as a region, and said no ratification took place.

When a referendum was held in 1998 for the second organic law, RA 8438, only Apayao voted in favor of autonomy.

CEB and CRA officials were also forced to address issues generated by CAR’s creation. The first fire that needed dousing was the “reverse discrimination” raised by residents who were not Igorot and who were concerned about their likely treatment under an indigenous Filipino region. This issue lingered for decades.

Land grabbing in the guise of ancestral lands also generated controversy in Baguio in 1989. Infighting almost always disrupted governance.

On Jan. 25, 1989, lawyer Sergio Kawi was appointed “titular head” of CAR and CRA. His title did not sit well with many Cordillera leaders, and Kawi was often mocked.

CEB and CRA had been inactive since the term of President Joseph Estrada when Congress stopped allocating their operating budget due to these squabbles.

Reforms

But the first years of CAR were also about aggressive, even revolutionary, reforms.

The concept of ancestral domain and the right of Cordillera tribes to decide how to use its resources were discussed by CEB and CRA, and were incorporated in the first draft autonomy law prepared by a Cordillera Regional Consultative Commission (CRCC).

RA 8371 (the 1997 Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act or Ipra), which allowed the issuance of titles to ancestral lands and ancestral domains, was crafted 10 years after CAR was formed.

Ipra owes much to extensive consultations in the Cordillera, where indigenous peoples’ land rights were championed.

In May 1989, the CRCC objected to the Senate version of what would become the first autonomy law for excluding provisions that allow ownership of ancestral lands, control of natural resources and recognition of indigenous systems of governance, among other things.

In August 1989, members of CEB and the Neda reviewed and challenged the national standards used for allocating government resources.

At that time, the standards for building roads and infrastructure were meant for lowland terrain, Tinggonong said. Road projects in upland communities required more funds that were not given to CAR.

This was crucial for the CAR economy. According to a discussion paper for the CAR regional development framework, the interim region had the lowest gross regional domestic product in the country from 1987 to 1992.

The region at that period was reeling from a 7.7-magnitude earthquake on July 16, 1990, that devastated Baguio City and nearby communities, and from a powerful typhoon that pummeled the region the following year.

The economy had improved since, although the region’s growth performance had been erratic.

On hindsight, Tinggonong said, “We [in CAR] could have focused more on preparing the people for regional autonomy and not [simply] implementing projects. More dialogs and discourses at the community level could have been done. But other CEB members did not have that orientation. They were unprepared.”

Scholars say the very advocates for autonomy like CPA and Balweg ended up obstructing their cause. The charismatic Balweg, for one, was treated with suspicion in most parts of the region.

CPA, Casambre said, campaigned against the autonomy bills in spite of the fact that it “had been principally responsible for getting the project of autonomy on the government’s agenda in 1986… not least because what they had won in the form of a constitutional provision had become perverted as soon as the government entered into `sipat’ (ceasefire) with the Cordillera People’s Liberation Army [of Balweg].”