Why Duterte administration should focus on teacher quality

The quality of a country’s education system cannot exceed the quality of its teachers, according to a 2007 study on the world’s top performing school systems.

The “boringly normal” underperformance of Filipino students in national and international tests can only mean one thing: Many teachers have not mastered the content of instruction.

Results of numerous assessments administered to Filipino teachers over the past 30 years have unequivocally shown this to be the case.

In its evaluation of bilingual education from 1974 to 1985, the Linguistic Society of the Philippines identified teacher quality as a major factor in the cross-sectional deterioration of achievement among pupils.

Noted educators Andrew B. Gonzales and Bonifacio Sibayan reported: “The relation between the low achievement of pupils and the lack of knowledge of the subject matter among teachers as revealed in the pupils’ and teachers’ tests is very clear; it is obvious that teachers cannot teach what they themselves do not know.”

If the passing grade in the teachers’ tests were to be set at 75 percent, Gonzales and Sibayan said, the average teacher in both elementary and secondary school would fail all of the examinations (even in Pilipino as a subject, the average was 68 percent).

Bottom half

The two educators said it was not difficult to explain the poor quality of teachers.

“Those who go into the teaching profession are those who are at the bottom half of high school graduates. If even the upper half are not good enough to do college/university work, how much more with those who are at the bottom,” they added.

Where have all the good teachers gone?

This deplorable situation has continued up to the present. Benchmarking studies during the past few years paint the same gloomy picture of the ill-prepared Filipino teacher.

Grades 1, 2 teachers

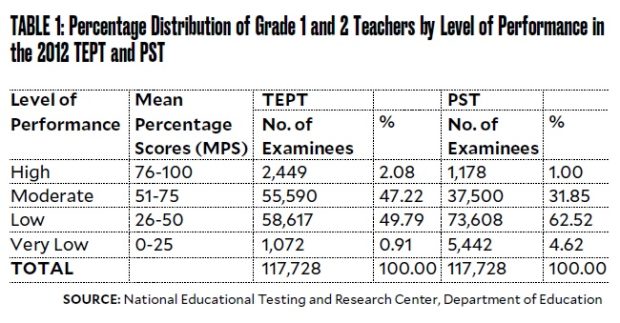

In 2012, close to 120,000 Grade 1 and 2 teachers all over the country took the Test of English Proficiency for Teachers (TEPT) and the Process Skills Test (PST) in science and mathematics. (The outcomes are shown in Table 1 on this page.)

In sum, results reveal that:

Only 2 percent of teachers were able to attain the high level (76-100 mean percentage scores, or MPS) in the English tests while a lower 1 percent were able to reach this level in science and math.

Most of the teachers—62 percent in science and math and 50 percent in English—got scores ranging from 26 to 50 percent.

In the PST, teachers scored highest in observing (72.25 percent), measuring and quantifying (55.48 percent) and making models (53.92 percent). They scored lowest in higher-order thinking abilities like inferring (21.40 percent), analyzing data (33.50 percent) and evaluating (33.50 percent), resulting in an overall low MPS of 46.03.

Little improvement

In 2013, it was the Grade 3 and 4 teachers’ turn to take the tests. The performance of this batch (totaling 99,963) showed little qualitative improvement from that of Grade 1 and 2 teachers the previous year.

Overall scores of Grade 3 and 4 teachers averaged a moderate 54.69 for TEPT while those for PST stood at a low 49.87.

In 2015, some 120,000 Grade 5 and 6 teachers took the tests and scored 58.23 percent in English and 54.05 percent in science and math.

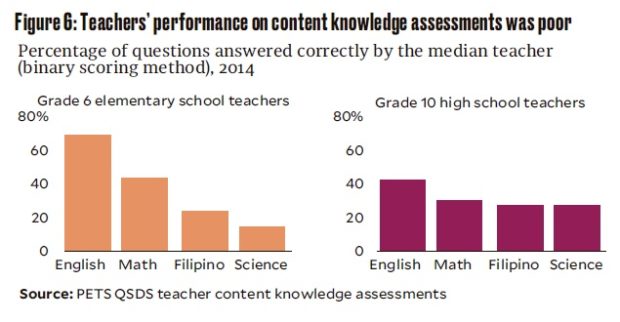

In 2016, the results of the Philippines Public Education Expenditure Tracking and Quantitative Service Delivery Study (PETS-QSDS), funded by the World Bank and Australian Aid, found teachers’ content knowledge to be “poor.” (See Figure 6 copied from the report.)

New teachers did not perform significantly better than “experienced” ones. And what was truly alarming was that most teachers were not aware of their own deficiencies and tended to rate their subject matter competencies highly.

Proposed action

What needs to be done?

The lack of cognitive language abilities and academic proficiency among Filipino teachers painfully illustrates the utter failure of teacher education institutions, the Commission on Higher Education and the Department of Education in addressing the critical issues related to teacher quality.

The Research Center for Teacher Quality (RCTQ), based at the Philippine Normal University and supported by SiMERR National Research Center-University of New England in Australia, has articulated in detail what needs to be done to improve the quality of teachers and of instruction.

RCTQ’s proposed action entails a “system” approach to education reform which includes:

Implementing evidence-based and nationally validated Philippine Professional Standards for Teachers. This set of standards contains a small number of indicators in seven domains across four career stages (beginning, proficient, highly proficient and distinguished teachers) that link pre-service and in-service growth. These standards, when approved by government, can become the framework of practice expected of all teachers across career stages and the basis for hiring, promotion and rewards.

Using results-based performance assessment tools for pre-service and in-service teachers at each career stage.

Developing a new preservice curriculum that is “outcome-based, compliant with the K-12 curriculum and linked to teacher standards.” Most teacher-education institutions are not preparing pre-service teachers to meet the minimum quality standard for a beginning teacher, according to RCTQ.

Designing professional development plans based on content test findings that offer a balanced approach to content and pedagogy. New practice-based masters and professional doctorate programs have to be reconfigured according to the K-12 curriculum, career stages and teacher standards.

Medium of instruction

In earlier articles, I have argued how the current “subtractive” system (where English as a second language (L2) replaces the first language (L1) as medium of instruction) has been extremely harmful to learning outcomes for both students and teachers.

It is this system that has hindered the intellectualization of our languages, thus preventing them from being our primary vehicles for gaining and creating new and higher knowledge.

Additive L1-based multilingual education (where the L2 adds to the L1 and where L1 is never exited as medium of learning) seeks to address this particular weakness and has fortunately been incorporated into the Philippine professional standards for teachers.

I urge all patriotic educators to dare to struggle so that teacher quality becomes the linchpin of President Duterte’s revolutionary agenda for Philippine education.