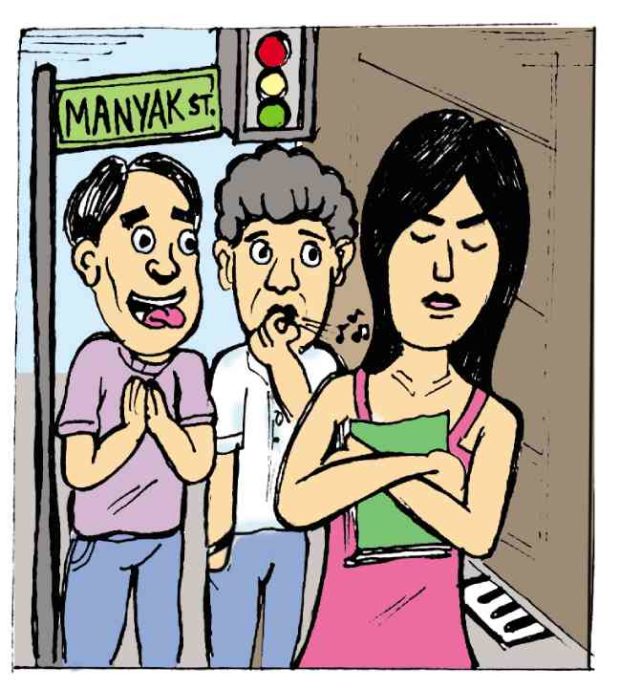

—illustration by jerito de la cruz

When she was 17 years old, Jamie (not her real name) had a harrowing experience inside a jeepney.

On her way to school, a much older man groped her breast from under her bag—not once but twice. She froze in her seat, scared and confused as to what to do.

“I tried to shield my chest, but he kept on doing it,” she said in an interview. “I was scared to make a scene … No one saw what he was doing to me.”

Seven years have since passed, but sexual harassment remains a common experience in the streets for Jamie, who now works as a production assistant for a media company. For many Filipino women like her, catcalls and wolf-whistles in public spaces have become shared ordeals.

With victims like them in mind, a protective initiative of a global scale is gaining traction in the country.

The United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN Women), in partnership with the Quezon City government, recently held a two-day conference for Metro Manila mayors to promote urban safety for women and girls.

Local interventions

Under the Safe Cities Metro Manila Programme, interventions would be done at the local level to prevent sexual harassment and violence in public spaces, like the streets and public transport systems.

Katherine Belen of the UN Women Safe Cities Global Initiative said there is a gap in addressing issues of sexual abuse in the national and local levels.

“We already have a national legislative framework, such as the Anti-Sexual Harassment Law, the Anti-Violence Against Women and Children Law, and the Anti-Rape Law,” she said.

But local governments could still pass legislation to prevent and respond to harassment in public areas.

“(They) actually have the autonomy to develop, implement and fund programs against public space harassment,” she added.

Landmark ordinance

In 2015, Quezon City became the first in the country to join the UN Women’s global flagship program, which then covered 26 other cities including New York, Mexico City and Cairo.

In March 2016, the city passed a landmark ordinance penalizing catcalling, stalking and lascivious acts directed at women, imposing jail terms and fines of up to P5,000 on violators.

This year, the Safe Cities program is expected to extend its implementation to 16 other local governments in Metro Manila, scaling up strategies to improve women’s safety through legislation and other programs.

“It’s hard if only one city has the law,” Belen said. “As you know in Metro Manila, a woman can live in Quezon City, but work in Makati. Every day, she travels across three cities along the way. If those other cities don’t have the same ordinance, it’s difficult to ensure the safety of the woman.”

The conference gathered representatives of the mayors, city planning officers, and staff of the gender and development councils of various LGUs.

Quezon City Mayor Herbert Bautista hailed the progress being made, but noted that the biggest challenge was still about changing the prevailing culture.

“What you’re trying to change here is the mindset and culture of boys, and even girls who are scared to speak up and complain,” he told reporters. “[With this program,] let’s start to cultivate a new perspective.”

12 complaints, 2 trials

A year after the Quezon City antisexual harassment ordinance took effect, only 12 complaints invoking it had been recorded in the city and only two were pursued and led to a court trial, Bautista said.

Still, Bautista considered this a “success” as he remained “optimistic that other cities would join the cause.”

“It won’t change overnight, but it has to start with ourselves, too,” he stressed.

Belen said the UN-backed Safe Cities initiative would not only benefit women and girls. “If you make your city safer for women, it makes the city safer for all,” she noted.

Jamie expressed hope that the fight against sexual abuse in the streets won’t be a lonely crusade.

“[The initiative] will give more encouragement for women to fight back,” she said. “If I see other women pursue cases, I feel empowered that I can fight back, too.”