In war-torn Marawi, tales of daring escape amid violence

MARAWI, Lanao del Sur — It was during a lull in the fighting that Rohaina Salic first heard it, the bellow of a distant voice telling civilians trapped in the war-stricken city of Marawi they could finally emerge from their homes.

She didn’t know whether the plea, projected from a megaphone blocks away, had come from the Philippine Army, or from black-clad militants linked to the Islamic State group who seized this mosque-studded town last month.

She had not set foot outside since the clashes—the worst to hit the country in years—began. But on this day, at least for this one precious moment, the guns had fallen silent.

And it was time to go.

“We didn’t really know whether it was safe to come out,” said the 38-year-old Salic, who walked out of the rubble of Marawi on Thursday with six members of her family. “We put all our faith in God.”

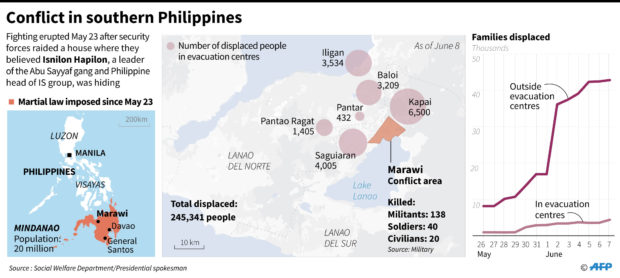

More than two weeks after Islamic militants plunged the lakeside town into chaos with an unprecedented attack that has killed close to 200 people and triggered fears that extremists are trying to gain a foothold in the country’s restive south, hundreds of militants remain stubbornly lodged in Marawi’s city center.

And every day, civilians like Salic trickle out with harrowing tales of survival, and escape. On Thursday, the lucky ones numbered 45.

But the violence is far from over. On Friday, a 15-year-old boy died from a stray bullet fired by a suspected enemy sniper as he prayed at a mosque in the village of Datu Saber. The victim was identified as Abdillah Dimangampong Masid, and reports reaching the military here said the bullet came from the direction of Mapandi village, where the gunmen are still believed holed out.

At least 16 soldiers were also wounded in clashes on Friday and were rushed to a hospital in nearby Iligan City.

Those who were lucky, like Salic, said her family was able to survive for two weeks because part of their residence is also a grocery, stocked with biscuits, instant noodles and soft drinks. They also had a large stock of drinking water, but used rainwater to wash their hands and the dishes.

The family had not had electricity since May 24. They lit candles each night as the crackle of gunfire echoed outside.

But on Thursday, it was the absence of gunfire that drove them out the door, only to find massive destruction in every direction.

Salic said her family—three children and four adults—crawled over rubble and under downed electricity polls. Rubble from the fighting blocked many streets.

Trust in Allah

Some civilians had managed to walk out, or run, on their own. Others were plucked by the Army or civilian rescue teams that were launching risky missions near the front lines with white flags wrapped around their vehicles’ antennae.

The evacuees who end up at the provincial government’s headquarters are met by doctors and nurses who check their vital signs and offer first aid and emergency care before sending them on to safer areas further inland.

Salic’s daughter, Aljannah, 7, carried a makeshift white flag, fashioned from a T-shirt and a pole they broke off of a household cleaning tool. As they neared an Army checkpoint, a single gunshot rang out. Aljannah made a move to run.

But Salic quickly grabbed her daughter’s hand and yanked her close.

“Don’t run,” she whispered. “Trust in Allah.”

Sittie Johaynee D. Sampaco, a Department of Health volunteer, said the new arrivals appear deeply traumatized, having spent days on end without food and water.

“Some of the patients can’t even speak. Some just cry and won’t interact with other people,” Sampaco said. “This isn’t over. We’re expecting to get much more.”

It’s unclear how many people remain trapped in Marawi. Authorities have put the figure this week at anywhere from 100 to 2,000. They include at least a dozen hostages, among them a Catholic priest and parishioners who were seized when gunmen stormed their Church shortly after clashes began on May 23. Their fate is unknown.

Children

At Badelles Multi-Purpose Hall at the Iligan City National School of Fisheries in Barangay Buruun here, 5-year-old Hamsa was unmindful of the people around him.

He did not even look when the Inquirer took shots of him as he held a blue crayon and scribbled lines in an attempt to lay color on an illustration of the Sarimanok, a colorful legendary bird that is part of the Maranao culture and literature. It adorns many buildings in Lanao.

“He’s always like that, he colors, he scribbles. He would play for some time, but then he’ll go back to coloring again,” Tarhata Mustari,19, Hamsa’s mother said. She was nursing a baby—her third child who was born while they were fleeing the violence.

Nearby, Karim, 7, was holding a pencil on one hand and a box of crayons on the other—while several children either played Scrabble, hula hoops, alphabetical tiles and other toys. Karim started drawing two parallel lines on paper with such pressure that his pencil snapped.

Asked what the lines were, he just made an empty gaze and said nothing. Social workers have yet to find out if his anger was caused by the fighting that forced his family to flee Marawi.

The children—which make up the majority of the 2,000 evacuees—were undergoing pyschosocial interventions, either in groups or by themselves.

“We’re still on our third day (Friday) and what we are doing now is to allow them more time to play,” Patricia Amante, a volunteer for Omega Team Philippines, said.

Omega is a Bukidnon-based group which also conducted psychosocial intervention sessions among children in the aftermath of the Tropical Depression “Sendong” tragedy.

Amante said they have not yet really interacted with the children to find out how the Marawi siege had affected them, but said there were clear signs of trauma. Many children here just wake up and cry, or would cower in fear when large objects fall on the ground or even just a sound of a plane passing by. —WITH JIGGER JERUSALEM AND AP