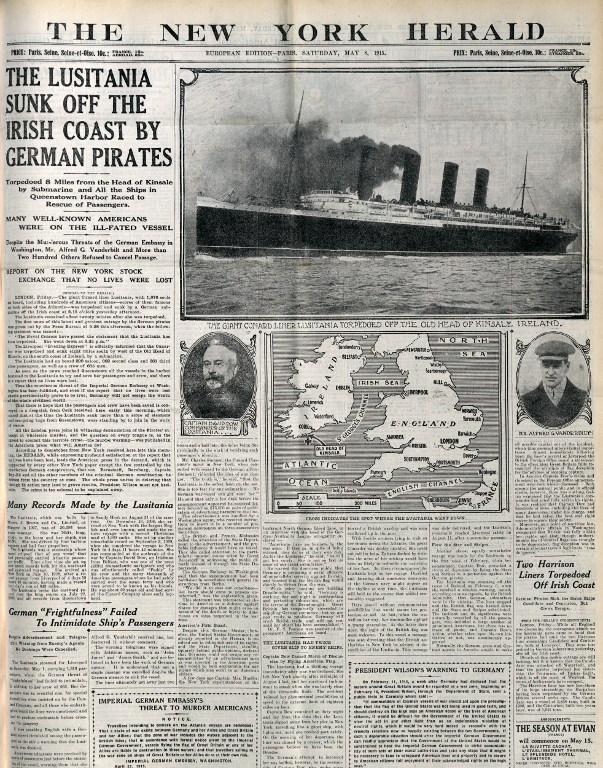

A picture released by the International Contemporary Documentation Library (BDIC) shows the front page of the newspaper “The New York Herald” dated May 8, 1915, announcing that the British ocean liner RMS (Royal Mail Ship) Lusitania was torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat, off Ireland, causing the deaths of 1,198 passengers and crew. It influenced the decision by the US to declare war in 1917. AFP

WASHINGTON — When America entered World War I, a century ago this week, the European powers were bogged down in a grinding trench war that had killed millions and ravaged the European continent.

Swinging its industrial might and vast manpower behind France and Britain against Germany and its allies on April 6, 1917, the United States tipped the balance of the conflict and marked its own emergence as a global power.

“World War I was clearly the turning point for developing a new global role for the United States, ushering in a century of international engagement to promote democracy,” said Jennifer Keene, a World War I expert at Chapman University in California.

Americans had been keenly following the war ever since it broke out in August 1914, showing broad support for neutrality.

But public opinion changed with the May 1915 sinking of the Lusitania.

The British ocean liner was en route from New York to Liverpool when a German submarine torpedoed it off the coast of Ireland, killing 1,201 passengers, including 128 Americans.

“It seems inconceivable that we should refrain from taking action on this manner, for we owe it not only to humanity but to our own national self-respect,” former president Teddy Roosevelt, an influential pro-allied hawk, told the New York Tribune at the time.

Pro-allied, but neutral

Although public sentiment swung toward the Allies, most Americans nevertheless insisted on neutrality.

Secretary of state Williams Jennings Bryan went so far as to resign in June 1915 over what he considered president Woodrow Wilson’s excessively belligerent tone toward Germany — especially after a US probe found that the Lusitania had been carrying contraband guns and ammunition.

Still, thousands of Americans volunteered to fight for the Allied cause, joining the French, British and Canadian forces. US aviators even joined the French Air Service, forming what became known as the Lafayette Escadrille.

People like Roosevelt worried that an Allied defeat would result in Germany’s occupation of parts of Canada, as well as British and French Caribbean possessions. Neutrality made German entry into the Americas more likely, Roosevelt argued in his influential newspaper columns.

“Americans had plenty of time to think about what they wanted to do, they just couldn’t agree,” said Michael Neiberg of the US Army War College.

Wilson, who struggled to maintain neutrality, won re-election in November 1916 under the campaign slogan “He kept us out of the war.”

A telegram, submarines and a revolution

Three events in early 1917 changed the equation.

On January 16, German foreign secretary Arthur Zimmermann sent a telegram to his ambassador in Mexico asking him to propose a military alliance. Mexico would recover land lost to the United States in an earlier war, including Texas, in exchange for German gold and weapons.

British intelligence agents intercepted the message, decoded it and passed on to Washington. Its publication outraged Americans.

Next, on February 1, Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare, sinking merchant ships without warning in international waters. The Germans calculated that if they could sink enough ships, they would starve Britain of food and supplies and tilt the war in their favor. They sank three US merchant ships in the subsequent days, adding to the anti-German outrage.

Even still, the Americans “will not even come,” German Admiral Eduard von Capelle confidently told a German parliamentary committee on January 31, “because our submarines will sink them. Thus America from a military point of view means nothing, and again nothing, and for a third time nothing.”

Finally, as Russia imploded in chaos and revolution, Czar Nicholas II abdicated on March 15, surrendering power to what became known as the Provisional Government.

Nicholas was “a figure that almost all Americans hated,” Neiberg said. “It thus seemed — at least until the Bolsheviks took over in November 1917 — that the war might usher in democracy.”

‘Safe for democracy’

Germany’s submarine war “is a warfare against mankind,” Wilson said in his April 2 speech to Congress asking for war.

“The world must be made safe for democracy,” he proclaimed. “We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion.”

But the US military was ill-prepared for war, its small, underequipped army having seen no major combat for decades. French and British trainers rushed over to train a force that grew at a breakneck pace, and by the war’s end in November 1918, more than four million Americans had been mobilized for the conflict.

In a show of bravado, the US military commander, General John Pershing, landed in France in June 1917 with 14,000 soldiers. The next months saw the arrival of a steady stream of inexperienced but enthusiastic US troops.

“The impression made upon the hard-pressed French by this seemingly inexhaustible flood of gleaming youth… was prodigious,” Winston Churchill later wrote.

Germany’s submarine campaign failed miserably as the Allies grouped ships in convoys protected by warships. No US soldiers were lost to German U-boats.

“There is no doubt that the US made a key contribution to victory,” Keene said, “but the Allied victory in WWI was a coalition effort — the US wouldn’t have won without the French or British, and the reverse is also true.”

Across the Atlantic, the American economy boomed with war spending. By the war’s end, it was many times stronger than any of the ravaged pre-war powers. US banks were also keen on collecting the $10 billion in loans made to the Allies during the conflict.

Peace prompted a new debate: are US interests best served by working through international organizations -– such as the League of Nations, proposed by Wilson in his January 1918 Fourteen Points peace proposals but rejected by the US Congress — or should the United States go it alone?

“That,” Neiberg said, “is a debate we’re still having.” CBB/rga