(First of three parts)

But to property developer Ayala Land Inc. (ALI) and landowner Sicogon Development Corp. (Sideco), the island had the makings of a world-class tourist destination with one hitch: 334.6 hectares of Sicogon were still classified as agricultural and occupied by 216 agrarian reform beneficiaries.

A settlement with the farmers in 2014 allowed the two companies to get the Department of Agrarian Reform (DAR) to approve the conversion of the property to nonagricultural use on May 29, 2016, the waning days of the Aquino administration.

As a result, the island is now being developed into a commercial and tourism hot spot of hotels, malls and residences, complete with a 1.2-kilometer airstrip.

Sicogon is just one example of converted agricultural lands that have since been turned into bustling hubs of activity, whether they be for residential, commercial, industrial or institutional purposes.

Between 1988, when the Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law (CARL) took effect, and 2016, a total of 97,592.5 hectares of agricultural land—the size of Metro Manila and Cebu City—were approved for conversion to nonagricultural purposes, according to the DAR.

The figure does not include pending applications for conversion, agricultural land reclassified by local government units and illegally converted land.

The rampant conversion of prime agricultural land, partly driven by rapid urbanization, population growth and speculation, has led to conflicting land uses.

Two-year ban

The DAR hopes to address the problem when it proposed a two-year ban on the processing of applications for land conversions last September.

If Malacañang approves the ban, the DAR will review all conversion applications made from June 15, 1988, to June 30, 2016, to account for “rampant and unchecked conversions of prime agricultural lands,” states a copy of the second draft executive order.

The ban would apply to all awarded lands under Republic Act No. 6657, or CARL, and other similar laws, according to Agrarian Reform Secretary Rafael Mariano.

“Essentially, the moratorium seeks to determine the status of agricultural lands, whether they have been developed according to their five-year development plan and its impact on agricultural production,” Mariano said.

Under CARL, land reform beneficiaries or landowners can apply for the conversion of agricultural lands into other uses if after the lapse of five years from its award the land stops being economically viable, or the area has become urbanized, and the land will have a higher economic value for residential, commercial or industrial purposes.

Of the approved conversion applications in DAR regional offices over the past 28 years, 80.6 percent of the land is in Luzon, with the provinces of Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal and Quezon (Calabarzon) that lie on the fringes of Metro Manila, taking up more than a quarter of the total. The Visayas accounted for 7.8 percent and Mindanao, 11.6 percent.

DAR regional offices approved a total of 40,308.8 ha while the national office approved 57,283.7 ha. Regional offices handle conversion applications involving 5 ha and below, while the national office handles applications involving more than 5 ha.

Calabarzon and Central Luzon produce big volumes of palay and other crops, lending credence to fears that conversion of prime agricultural lands could undermine food security.

Urbanization, population growth

The Philippines has roughly 30 million ha of land, of which 9.7 million are considered agricultural.

Rapid urbanization and population growth are major drivers of land conversion, according to Agrarian Undersecretary Luis Pañgulayan.

The need for housing and employment as well as the need to spur economic growth and investments have led the state to tolerate massive conversion of agricultural lands into other uses outside Metro Manila.

Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Rizal and Bulacan provinces all posted higher population growth rates than Metro Manila and the country between 1990 and 2015, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA).

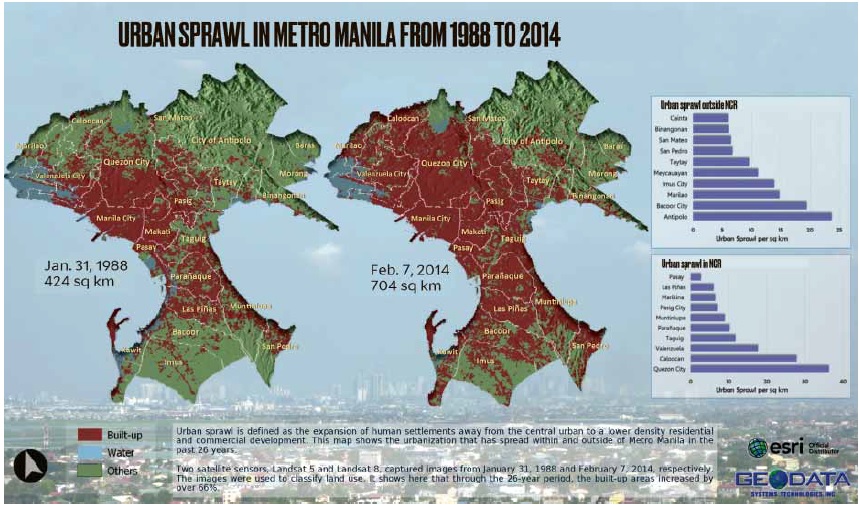

Satellite images of Metro Manila from 1988 to 2014 also showed that the urban sprawl nearly doubled. Built-up areas, or intensive-use lands that are mostly covered by structures, extended from 424 square kilometers to 704 sq km, well into bedroom communities, such as Bacoor City (Cavite); San Pedro City (Laguna); San Mateo, Taytay and Antipolo City (Rizal); and Marilao in Bulacan.

Incidentally, the provinces surrounding or near the capital have the highest land conversion rates since 1988.

Such was the case with Batangas province, where the DAR approved on Feb. 1, 2016, the conversion of 27 ha as additional area for a solar farm in Calatagan town. Solar Philippines Commercial Rooftop Projects now has the largest solar farm in the country with 160 ha, on which rice, corn and other crops used to be planted.

Urban land constraints

An expected surge in conversion applications in the Visayas and Mindanao as they, too, become more urbanized, was also key to his decision to propose the ban, Mariano said.

The DAR noted that Negros Occidental and Misamis Oriental, known for vast sugarcane and coconut plantations, respectively, were among the top 10 provinces with the biggest number of conversions.

If not properly addressed, the rapid urbanization across the country could pose major challenges to land management and economic growth.

This could lead to “congestion diseconomies” in which a lack of coordination between urban growth and land development could drive prices of land and demand for housing higher, according to a study on urban land constraints by Makiko Watanabe, senior social development specialist at the World Bank.

Watanabe presented the study at a conference on sustainable land governance in Manila on Feb. 8.

Agrarian reform beneficiaries

In Sicogon, the farmers, who initially opposed the joint venture project of ALI and Sideco, relented after their homes were destroyed in 2013 by Supertyphoon “Yolanda” (international name: Haiyan).

The agrarian reform beneficiaries entered into a compromise deal with ALI and Sideco in November 2014. The companies agreed to set aside P114 million for resettlement housing on a 30-ha property and livelihood projects, and donated 40 ha for “scientific” farming.

It is cases like this that the DAR would like to reevaluate should a conversion moratorium push through.

Mariano said his office would create a task force to spearhead a program review, monitor the lands of approved conversions and determine whether any of these need to be revoked. It would also seek out each farmer-beneficiary to ask the all-important question: Did their lives improve?

Pañgulayan said that over the course of CARL, 4.7 million ha of land had been awarded to 2.7 million farmers. “The question of Secretary Mariano is where are these beneficiaries now? Are they still tilling the soil?” he said.

“Historically, the farmers have paid for the land that they are supposed to get now. They shed blood, sweat and tears for the land through generations,” Pañgulayan said. “It belongs to them.” —WITH A REPORT FROM INQUIRER RESEARCH