She deserves a room of her own, this woman who resisted the coming of darkness during the martial law years and became an inspiration in that time of untruth, lawlessness and injustice.

Justice Cecilia Muñoz Palma already has a government building and a public school named after her, but the eponymous museum opened last week at the mezzanine floor of the Quezon City Hall complex may yet be the best tribute to this magistrate who dared defy former strongman President Ferdinand Marcos.

Occupying a whole wall in the museum is a black-and-white mural depicting the excesses wrought by martial law and captioned “Darkness descending (Pagsapit ng Karimlan),” around which are memorable quotes from Palma and other brave souls from that period.

Palma’s dissenting opinion—prominently displayed in a bound copy of similar decisions—on the habeas corpus case of Sen. Jose W. Diokno prompted the release of the human rights lawyer who had been detained for years without charges.

Palma also ordered the case of jailed Sen. Benigno Aquino Jr. transferred from a military to a civilian court to ensure a fair trial.

For such defiant moves, this Marcos appointee was called ingrata (ingrate) by a colleague, a description she wore like a badge of courage.

Her retort: “When I took my oath of office, I said to myself that my loyalty is not to the appointing power but to the Constitution, to justice and to the Filipino people.”

Indeed, the museum holds historic documents, photographs, video documentaries, artifacts and other memorabilia that bear witness to this woman’s contribution not only to law and justice, which was her field of expertise but more importantly, to the country’s awakening in its darkest hour.

Tribute to excellence

The museum occupies some 140 square meters, a compact easy to navigate space with items curated by Philippine culture expert Marian Pastor Roces.

The museum too might well be a tribute to excellence, as Palma was a woman of many firsts: the Philippines’ first woman prosecutor, first woman district judge, first woman in the Supreme Court, and “the first woman in the world assigned to lead the creation of a constitution,” in reference to the 1987 Constitution.

Just as prominent in the museum’s timeline about her life was how Palma stepped prominently into the scene in 1973 when martial rule heralded a difficult chapter in Philippine history.

The timeline near the museum’s entrance is delicately embossed on glass and shows the life and times of this Batangueña and her family, her early schooling at St. Bridget’s College in Batangas and at St. Scholastica’s College in Manila where she graduated high school valedictorian.

She was also college valedictorian at the University of the Philippines College of Law, where she met fellow law student Rodolfo Palma who became her husband. They raised three children.

Palma topped the bar exams in 1937 with a grade of 92.6 percent.

The photographs in her timeline highlight the seasons in her life: the child Celing in an angel costume and in gowns as she approached maidenhood. They also celebrate her many roles as wife, mother, judge, Supreme Court Associate Justice, assemblywoman, constitutionalist, God’s faithful servant.

1987 Constitution

At the center of the museum is a copy of the 1987 Constitution crafted by a constitutional commission presided by Palma as its president, which museum guests can peruse freely.

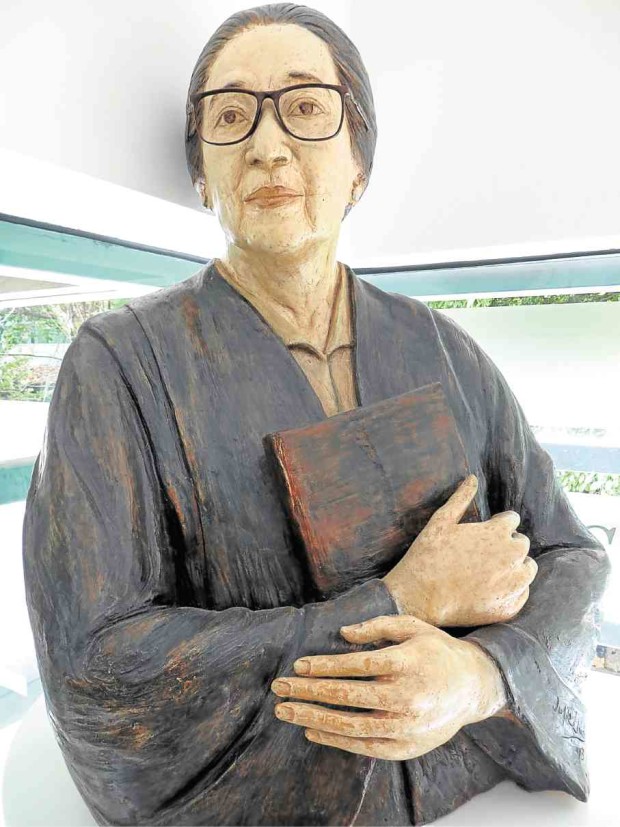

A life-size plaster bust of Justice Palma by sculptor Julie Lluch stands in a corner beside the words, “Idealism, Spiritualism, Patriotism.” The words are described as panindigang buhay, (principles that) Palma lived by. A weighing scale representing justice rounds up the display.

Standing silently in its own corner is Palma’s electric organ, on which she had played many musical pieces when she was not busy in court. Her mother had hoped she would be a pianist, but the mischievous girl in blue convent school uniform proceeded to law school instead. The music never left her.

Also displayed are Palma’s written works, among them “Mirror of My Soul,” a collection of speeches and decisions she had penned; personal items such as the toga she wore when she was Supreme Court justice, as well as paintings, letters and articles about her. Distinct among these items is an illustrated children’s storybook on her titled “A Life Well Lived.”

Museum visitors may also choose to watch several video documentaries—on Palma’s personal life, the martial law years, and the constitutional assembly.

Before the museum was set up, the building that houses the prosecutor’s and the Public Attorney’s Offices and the space that the museum now occupies was already called the Justice Cecilia Muñoz Palma Hall. By its entrance is her image mounted on a pedestal, around which people happily snap selfies.

Such public admiration and the museum itself affirm Justice Palma’s prescient reminder: “We shall be judged by history, not by what we want to do and can’t, but by what we ought to do and don’t.”