The 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution succeeded in dismantling the Marcos dictatorship, but its failure to realize the promised change under democracy paved the way for another populist strongman in the person of President Rodrigo Duterte, an American historian said.

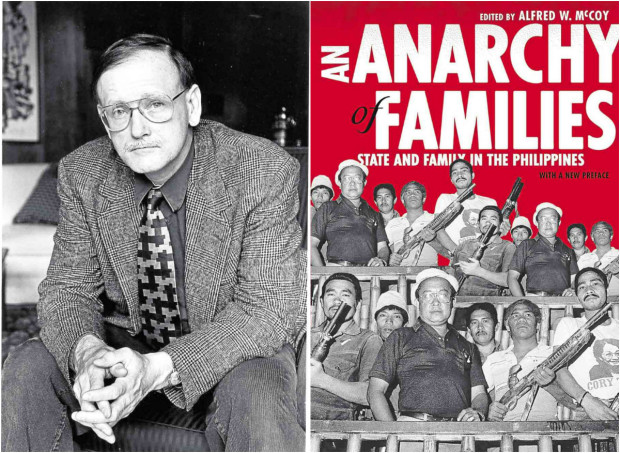

The dreams of Edsa failed because former President Cory Aquino resorted to localized violence to suppress countryside ferment, said Alfred McCoy, an expert in Southeast Asian studies who authored two books—“An Anarchy of Families” and “Closer than Brothers: Manhood at the Philippine Academy”—that investigated Filipino political dynasties and the military institution.

President Duterte, who won last year, has promised “to bring change,” a vow that has captured the imagination of Filipinos aching for reforms since the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution ousted Marcos and installed Aquino.

But like Marcos, Duterte has used “localized bloodletting” even as he promised order and development for Filipinos, McCoy said.

Among his campaign promises was to fatten the fishes in Manila Bay, where he said he would dump thousands of dead drug addicts and criminals. Rights groups say that since he took office, more than 7,000 have died in his war on drugs.

“All of the new populist leaders around the world, they always promise change, they always say they are the sole owner of change, that they can make the change happen. This is a very unrealistic position,” McCoy said.

“In any large complex society, no single individual, not even the head of state, can actually produce meaningful change. It’s got to come from the participation of the citizenry,” he said.

McCoy said like Marcos and Aquino, Mr. Duterte could face a threat from the military, which he said moved “very quietly.”

“You will never know it’s going to happen until it happens,” he said. “One of the things about the military is that it’s complex. From any level, from lieutenant colonel onward, you can get a core group that will oppose you (and) they don’t talk about it before they do it,” McCoy said.

“That’s why he (Duterte) has to be careful in handling the military. Duterte has to manipulate the chain of command.”

Coup virus

“It’s a possibility that if he moves too far to change, like he is giving away territory in the South China Sea, this could produce a very strong nationalist reaction among the military,” McCoy said.

He said there was a “possibility” that President Duterte would declare martial law as a means of consolidating power, since he has openly talked about it.

But the military would likely oppose an authoritarian regime, having learned a valuable lesson 31 years ago.

In February 1986, thousands trooped to Edsa to protect then Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile and Philippine Constabulary chief, Gen. Fidel Ramos, who withdrew support from Marcos, citing massive cheating in the snap election among their reasons.

The near bloodless revolt toppled Marcos from power, ending his brutal two-decade regime.

Disgruntled soldiers with links to Enrile would later launch at least seven coup attempts against Aquino, who was installed after Marcos.

American jets saved her from ouster during a December 1989 coup, the strongest launched by rebel soldiers.

But a retired general, who spoke to the Inquirer on the condition that he would not be named, said that the “coup virus is dead” at present.

He said today’s military has undergone a serious and in-depth transformation. This includes a “transformation roadmap” where each soldier is given a performance “report card” and assessed by civilian stakeholders. The roadmap would be implemented until 2028.

“The soldiers are taught that they cannot be professionals if they are not experts in their work. Being professionals also mean adherence to human rights and the respect for the rule of law,” the general said.

At the core of this roadmap, he said, is the constitutional mandate of the military “as protector of the people and the state, and to ensure the integrity of national sovereignty and territory.”

Thus, McCoy was right in his assessment that Mr. Duterte’s pro-China leanings may push the military against him.

McCoy was in Manila to keynote a two-day international conference to mark the 40th year of the Third World Studies Center at the University of the Philippines in Diliman, Quezon City.

In his keynote speech, McCoy said democratic countries have been known to produce populist leaders “who promise to overturn the past, overturn conventional wisdom” through the use of violence.

This had happened in the past, and it’s happening again today.