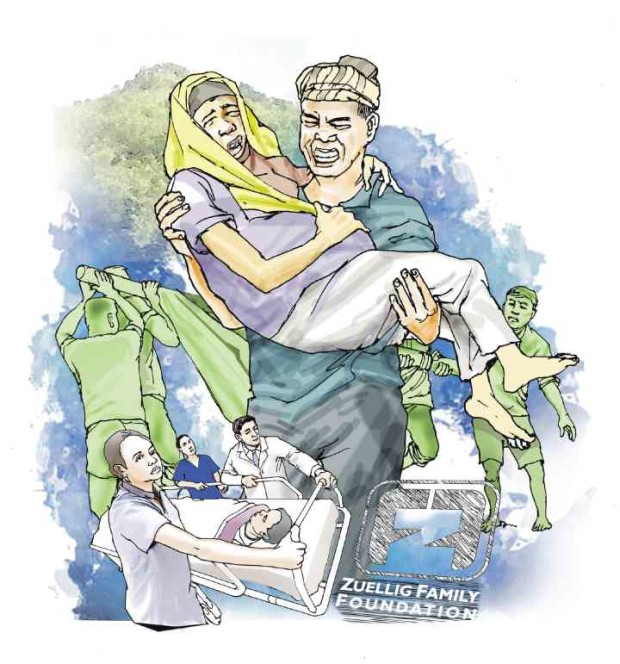

As a young boy, Alih Sali would hear stories of mothers and their babies dying during childbirth “because of poverty, the lack of knowledge on health issues and the need to endure long travel on rough roads to get to the nearest hospital in town,” the former police inspector and now vice mayor of Akbar, Basilan, recalled.

But going around the province as a police officer made Sali realize how other towns had grappled with the same problem and made their health systems work.

“I asked myself, ‘If they can do it, why can’t I?’” Sali said at recent rites that honored a growing number of local chiefs who have become health champions in the conflict-stricken Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM).

Sali was among the local leaders from 19 municipalities in the ARMM recognized for completing the two-year health leaders for the poor program under the Zuellig Family Foundation (ZFF). The health leadership and governance program was a partnership among the ZFF, the Department of Health and the United States Agency for International Development.

Under the program, mayors and municipal health officers were trained on leadership and service delivery and were expected to improve health indicators in their areas using as roadmap the World Health Organization’s six building blocks of health. These are: leadership and governance; health-care financing; health workforce; medical products and technologies; information and research, and service delivery.

Also recognized for wielding their power to save the lives of pregnant mothers and newborn babies were Mayor Rahiema Salih of Tandubas, a third-class municipality in Tawi-Tawi, and Rauf Talib Mastura of Sultan Mastura in Maguindanao.

The Philippines has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in Southeast Asia. In 2015, there were roughly 114 mothers dying in childbirth per 100,000 live births in the country, way beyond the Millennium Development Goal target of 52 women per 100,000 live births.

A new target has been set under the Sustainable Development Goal, which has countries committing to reduce global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births by 2030.

Folk healers

Sali recalled how, in the early years following the creation of Akbar, the nearest public and private hospitals in Lamitan were almost two hours away, which often discouraged residents from seeking proper medical treatment. Their only option, he added, were folk healers for the sick, and the “panday” and “hilot” for women who prefer to give birth at home.

In 2013, an incident that had a mother and her newborn dying 24 hours apart jolted Sali enough to ask religious leaders to use their Friday sermons to convince mothers to go to health facilities for childbirth.

Traditional healers and panday and hilot were also recruited as barangay health workers who were given a P1,000-incentive for every pregnant mother they bring to the birthing clinic. Mothers who seek professional medical help were compensated as well with a free birth certificate. At the same time, Sali enacted an ordinance to mete out stiff penalties to traditional healers who stubbornly practice their trade.

The first to be chastised by the ordinance was his own grandmother who was summoned to the police precinct to pay a P1,000-fine for initial offense. Sali said his poor grandmother had to ask money from him for the penalty.

“I gave her the money in exchange for her promise not to assist pregnant women at home anymore,” recounted Sali, who was appointed mayor in 2006 of the then newly created and impoverished municipality of Akbar.

At first, it was hard to convince traditional healers to stop the practice that put many mothers and babies in danger. But a monthly gathering with the municipal health officer slowly reshaped their beliefs and habits and made them well-informed barangay health workers, said Sali.

No IRA

Since 2014, Akbar has managed to achieve zero maternal and newborn deaths and improve facility-based deliveries from a dismal five percent in 2013, to 94 percent this year.

This, without having a share in the Internal Revenue Allotment (IRA) for nearly a decade now, the mayor pointed out.

Salih has a similar story of reversing the chronic health problems of Tandubas, but only after she overcame the rift between her and the municipal health officer, and realized that collaboration between them was important.

“It was not because we were fighting,” Salih said in a speech. “We just didn’t have enough reason to collaborate except on occasions when the rural health unit needed extra money or I needed to address an event as mayor,” she added.

“I also heard things about the municipal health officer that I didn’t like,” Salih said. But the frosty relations thawed when the leadership program brought them together.

In 2014, the two officials sat down for the first time to map out an action plan to address maternal and infant deaths and other health issues in this town located northeast of Tawi-Tawi.

The renewed alliance resulted in zero maternal deaths in Tandubas since last year and a surge in facility-based deliveries from 85 percent in 2015 to 90 percent this year.

Mastura meanwhile worked to sustain the gains made by his predecessor, his father Armando, in eliminating maternal deaths and fixing poor health-seeking behavior among pregnant mothers in Sultan Mastura.

Despite the absence of a municipal health officer and public health nurses, the small town of less than 5,000 households has been recognized as one of the first two ARMM municipalities to have reached the national target of 90 percent in facility-based deliveries and skilled birth attendance.

To stem the persistent problem of women’s preference for home births, Mastura worked with his health team on a program that gave pregnant women priority coverage under the Philippine Health Insurance Corp. (PhilHealth), on condition that they complete four prenatal checkups.

“Among Muslims, mothers weigh three times more than fathers. It only goes to show how important mothers are in our society,” said Mastura.

The strategy raised the rate of facility-based deliveries and skilled birth attendance to 91 percent middle of last year.

“We achieved these results through dedication, teamwork, proper programs, tight coordination and right incentives,” Mastura said, referring to the midwives’ share in incentives under PhilHealth’s maternal care package.

Good governance

“We celebrate because we have more Moro health champions whose good governance practices will reduce health inequities in their region, which is the poorest in the country,” said ZFF chair Roberto Romulo at the culmination of the health leadership and governance program.

Romulo said the ratio of births assisted by skilled birth attendants in the 19 ARMM towns rose from 54 percent in 2013 to 75 percent on the first half of 2016.

The rate of facility-based deliveries also surged from a dismal 23 percent in 2013 to 60 percent in the first half of 2016, he added.

The municipalities that reached the 90-percent target were Taraka and Masiu in Lanao del Sur; Sultan Mastura in Maguindanao; Sibutu in South Ubian; Tandubas in Tawi-Tawi; Kalingalan Caluang in Sulu, and Akbar in Basilan.