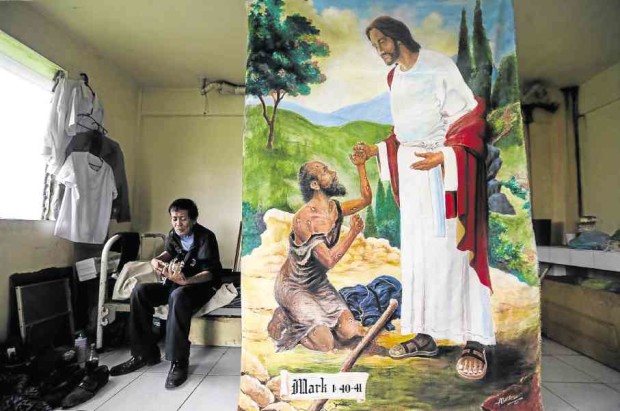

Since 2014, the artist-musician has been producing masterful works from his small living quarters at Tala Leprosarium. —PHOTOS BY LYN RILLON

We call someone like Albert Lacson Lopez a multihyphenate, a man of many talents and passions. He’s a veteran comics illustrator, painter-sculptor, writer-musician, and, in his younger years, a bodybuilder buff enough for action movies.

But a diagnosis in November 1996 once crushed his spirit and snuffed out his inner fire. It sent Lopez packing and stuffing his whole life into his car for a long drive from his Parañaque City residence to Dr. Jose N. Rodriguez Memorial Hospital in Tala, Caloocan.

He would spend bitter months in the government-run facility as a PAWL—or a person afflicted with leprosy.

Lopez eventually won his battle against the affliction also known as Hansen’s disease. But while his body survived the fight that had forced him into seclusion, his personal relationships suffered along the way and still needed healing.

He found himself returning to the hospital in 2014, not with new sores but with a new life purpose. The once-prolific artist behind classic Pinoy comic series like “Gorgonya” and Mars Ravelo’s “Captain Barbell” is now known at the Tala Leprosarium simply as “Tatay Bert.”

Chief chronicler

Now aged 71, he serves as a chief chronicler of the lives of PAWLs, immortalizing their stories through art and song. He has been producing works from his living quarters below one of the hospital wards, in a small room practically bereft of personal effects save for a few shirts hanging by a window.

A six-foot-tall painting of Jesus blessing a leper, as told in the Gospel of Mark, dominates this creative sanctuary. Beside it is another artwork in progress—a relief sculpture of a doctor surrounded by leprosy patients, their faces modelled after actual patients at Tala. On the wall are smaller paintings depicting the same woman, another leprosy patient, retracing the time she was free of the disease.

These are all commissioned works for a “leprosy heritage museum” that the hospital plans to set up to preserve its history and the stories of PAWLs. Lopez started working on them in 2014, after Dr. Rowena Oropesa, head of the hospital’s heritage restoration committee, asked him to come back and be the primary artist for the museum.

Established in 1930, Dr. Jose N. Rodriguez Memorial Hospital serves as a sanitarium and hospital for patients with leprosy, a chronic disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae that primarily affects the skin and peripheral nerves and defined by disfiguring pale-colored skin sores and lumps.

In less compassionate times, lepers were segregated from society and left alone to die in far-flung colonies. While the disease is curable and declared eliminated as a public health concern in 1998, patients and even those who have long recovered continue to be regarded as “unclean” and even “sinful”—a stigma that harked back to Biblical times.

Currently, the leprosarium in Caloocan is home to 65 PAWLs. The latest to be admitted, on Jan. 13, was Oropesa’s own 85-year-old mother.

But some former patients have chosen to stay, having faced discrimination outside—as well as the difficulties of reconnecting with their families.

“If it were up to me, I would have left this place already,” Lopez told the Inquirer in an interview. “But my heart is here with them (PAWLs). I want to give them hope, and show them that there is life outside this disease. It’s a sacrifice… I’m all alone now.”

Troubled home

And he had been so for most of his life, he said. Born in Capas, Tarlac province, in June 1945, Lopez lived with his parents and four siblings in Project 7, Quezon City, before domestic problems made him run away from home at age 12.

He turned to friends, and sometimes strangers, for shelter and was already in his teens when he returned home. He then discovered the wonders of comics in Liwayway magazine and related publications and told himself: “Kaya ko ito, ah! (I can do this!)”

Lopez first finished his architecture course in Mapua. He didn’t take the licensure exam, however, and instead flew to Japan to form a band named Combo, where he was lead singer and guitarist.

When he returned to the Philippines after six months, Lopez also re-entered the world of “komiks,” doing freelance work for various publications like Liwayway, Tagalog Classics and Hiwaga. He also did illustrations for The Manila Times, after no less than National Artist for Literature Alejandro Roces asked him to join the newspaper.

He takes pride in works like “Amasonya,” a Pinay version of Tarzan; “Atomax,” a comic strip he did for The Times; as well as “Gorgonya,” “Captain Barbell” and “Darna,” which he drew in collaboration with leading graphic novelist Mars Ravelo.

As a bodybuilder and stuntman, Lopez appeared in several action movies; he made special mention of the 1986 flick “Kamagong” starring Lito Lapid.

In 1994, he was a master of his craft and a proud father of a young girl when the “scars” started appearing—first on his forehead and chin, later on the body. Then there was the loss of sensation.

“I was into weightlifting during those days. I was ignorant. I thought I developed scars because I dove straight into the pool right after doing barbells,” he recalled.

Friends and family started to avoid him. But it took him two years to finally see a physician at United Doctors Medical Center, where he was told he had leprosy. Later that same day, he was admitted at Tala, one of the only eight leprosariums in the country.

He arrived there in November. Living in a cramped ward and with the holidays approaching, surrounded by other PAWLs whose lives were thrown off course by the disease, he went into depression and lost the will to live.

“I threw away everything: my visa, passport, my comics and sketches. They became useless to me. Nobody visited me; I felt so alone. I even blamed God: ‘Why me? Wasn’t I a good enough person?’”

“But sometimes I would draw and compose songs, and my fellow PAWLs would admire them. I started fighting back. I wanted to show them that not all PAWLs simply wait to die,” he said.

By January 1997, he was completely cured. He left Tala and found a job as a woodcarver in Paete, Laguna province. He later moved to Boracay Island and offered his sculptures and paintings to tourists. He would still do comics now and then, though getting rusty because of his age.

Called into service

“Life was normal again. But the people who knew me before … I couldn’t blame them for staying away. It’s the stigma, the lack of awareness [about leprosy],” he said.

So when Dr. Oropesa asked that he lend his skills to the planned leprosy heritage museum, Lopez returned to live among the last of the Tala leprosy patients, this time as an artist.

Plans for “Museo Tala” are already on the drawing board, Oropesa said. Its mission is to remind the public about the patients and “how they suffered” before advances in medicine and therapy offered them hope.

With the help of architect Rajelyn Busmente, the hospital hopes to convert the leprosarium’s old Narra Room and have the museum completed by 2019.

With the project expected to cost P20 million, the hospital is counting on the Department of Health and private donors for funding.

So there is no stopping Tatay Bert from wielding magic through his brush and chisel. Lopez had already finished several works for the museum, including the Gospel painting, the busts of Dr. Jose Rodriguez, and portraits of PAWLs and survivors. For now, these pieces are on display around the hospital.

“I hope that, through my example, people would realize that [PAWLs] are not useless. Just because you got sick does not mean you lose all interest in living. Others may fall into a rut—sleep, eat, sleep, eat—and stop dreaming. Me, I still want to do many things.”

Lopez expressed such hopes in a song he had composed at Tala, titled “Tanging Dalangin” (Special Prayer):

“Gumuho man ang aming mga pangarap / Mga pagsubok ay pinaglalabanan / Ang aming dalangin sa Diyos nating mahal/ Ay tanggapin kami ng lipunan!”

(Our dreams may crumble, / Test our will to fight. / What we ask our beloved God / Is for society to accept and treat us right!)/rga