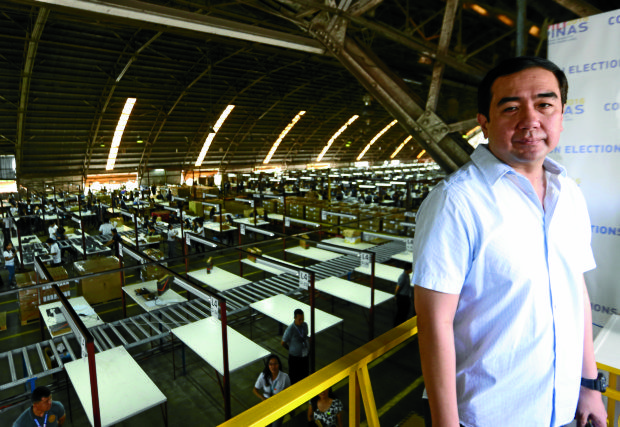

UNDER FIRE Andres Bautista disputes the National Privacy Commission’s finding he was grossly negligent and criminally liable for the leak of millions of voters’ data. —INQUIRER PHOTO

What a difference one month makes.

In December, Commission on Elections (Comelec) Chair Andres Bautista basked in the glow of an agency that was hailed globally as the Electoral Commission of the Year for the successful May 9, 2016, polls.

A month later, he was facing potential criminal prosecution over the March 2016 hacking of the Comelec website that has since been described as one of the worst breaches of a government-controlled database.

The National Privacy Commission said on Thursday that Bautista had committed “gross negligence” under the Data Privacy Act of 2012, or Republic Act No. 10173.

This came to light following an investigation of a “data breach” from March 20 to 27 last year. The breach exposed almost 77 million voter registration records. Sensitive information, such as voters’ full names, addresses, passport details and birthdays were posted on online platforms and a website that has since been taken down.

So notorious was the event that it even has its own name: Comeleak.

Criminal prosecution

At a press briefing on Thursday, privacy commission officials, led by Commissioner Raymond Liboro and Deputy Commissioner Dondi Mapa, announced that evidence to aid in the criminal prosecution of Bautista had been turned over to the Department of Justice (DOJ), which was expected to pursue the case.

The officials were quick to note that the breach did not compromise, in any way, the May 9 elections.

“The Comelec, in fact, protected the vote. The question is, in its zeal to protect the vote, did it fail to protect the voter?” Mapa said.

No data protection officer

The privacy commission probe found that the Comelec indeed failed in this regard and its decision dated Dec. 28, 2016, detailed how the Comelec and Bautista violated several provisions of the Data Privacy Act.

The privacy commission was organized last year, and its implementing rules took effect in August 2016.

According to the findings, the Comelec did not even have basic data privacy principles, as it had no existing policy covering data privacy and even lacked a data protection officer.

“What is clear is the lack of appreciation on the part of the Comelec chair that data protection is more than just implementing security measures, but must begin from the time of collection of personal data, to its subsequent use and processing up to its storage and destruction,” the privacy commission said in its decision.

“Absent within the Comelec was any policy on how to hold, collect, classify and store information in a safe manner and according to the law,” Liboro said. “We did not recommend the prosecution of Chair Bautista just because Comelec’s data was breached.”

Mitigate risks

Liboro added that while no system was impregnable in case of an online attack, the measures outlined under the law could mitigate those risks.

The privacy commission said “with dismay” that “there was no officer who took responsibility for maintaining data privacy and protection, and for compliance with data privacy and protection laws.

“In the absence of such a data protection officer, it falls upon the head of the agency to ensure compliance,” the decision said.

The breach hit several databases, according to the privacy commission.

There was the voter database in the Precinct Finder web application with 75.3 million records, the database in the Post Finder with 1.38 million records, the iRehistro database with 139,301 records, the firearms ban database with 896,992 records (20,485 firearms’ serial numbers) and the Comelec personnel database, with 1,267 records.

The privacy commission said the database in the Precinct Finder contained complete names, birthdays, gender, civil status, address, birthplace, disabilities, voter ID, voter registration record numbers, among other information.

Passport, tax ID info

The Post Finder application had even more details, such as passport information, biometrics description, taxpayers’ identification numbers, mailing addresses, citizenship, names of spouses, voting history, profession, height, weight and physical identifying marks.

The privacy commission said “unknown actors” using different networks and IP addresses extracted contents from the Comelec website, including information from voters’ databases, from March 20 to 27 last year.

On March 27, a group called Anonymous PH claimed to have defaced the homepage of the Comelec’s website. That same evening, a group called LulzSec Pilipinas said it downloaded the entire Comelec website and extracted files totaling 320 gigabytes.

The files were then uploaded to file-sharing platforms. The Comelec got wind of the act when the information went viral online.

“These data are most likely in the hands of criminal elements, and may be used at any time in the near or far future for malicious ends,” the privacy commission said.

Corrective measures

The commission also ordered several “corrective measures” for the Comelec.

It ordered the Comelec to appoint a data protection officer within one month, conduct an agency-wide privacy impact assessment within two months, and create a privacy management program and breach management procedure in three months.

The commission also recommended that the DOJ open an investigation, under the Cybercrime Prevention Act, of its finding that one of the computers used in the Comelec data breach had an IP address registered with the National Bureau of Investigation.

In the same decision, the privacy commission said there was not enough evidence to recommend a criminal complaint against Comelec officials Christian Lim (commissioner), Al Parreño (commissioner), Jose Tolentino Jr. (executive director) and James Jimenez (director).

The commission said Section 26 of the Data Privacy Act detailed a prison term of three to six years and a fine of P500,000 to P4 million.

Section 36 added penalties for an offender who is also a public officer—disqualification from public office for a period equivalent to double the term of the criminal penalty.

Sought for comment, former Comelec Commissioner Gus Lagman, an IT expert, said the poll body should follow the privacy commission’s recommendations to protect the data of millions of voters.

“This is information we are talking about. This is just as important as money. They should really implement features so that those databases are not hacked and leaked,” Lagman said. —WITH A REPORT FROM JULIE M. AURELIO