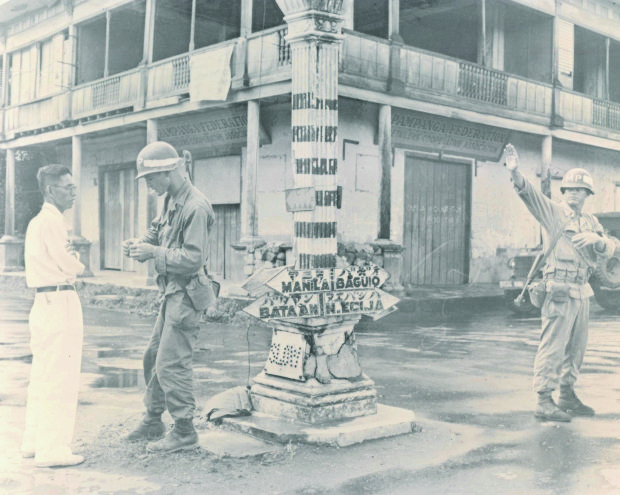

OLD TOWN CENTER The town center of San Fernando in Pampanga province used to be the gateway to other Central Luzon provinces. The Santos house in the background is still standing but is two buildings away from SMSan Fernando Downtown. —PHOTO COURTESY OF CITY OF SAN FERNANDO TOURISM OFFICE

(Third of four parts)

Shopping malls outside Metro Manila are creating jobs and livening up laid-back towns as the spearhead of the consumerist culture redraws the provincial landscape and changes the way Filipinos in urbanizing areas do business and trade.

When retired banker Angelo David, 84, was much younger, his hometown of San Fernando, Pampanga province, had a central “poblacion” and a large square where he and the other children played “sipa” and where the public market was one of the busiest parts of town.

The square is now a parking lot used mostly by customers of a nearby shopping mall. And gone are some of the other landmarks and shops of his boyhood days—Yap Tim Yan hardware, Letty’s Carinderia, Guan Yek Clothing and the well-loved 1980s snack house Kit’s. Where they once stood had risen gift and knickknacks shops, a fruit stand and a bakery supply store.

Department stores

In Davao del Norte province, maid Flordeliza Aquino said the “malls” of her youth in Tagum, her hometown, were just department stores and large grocery shops owned by Chinese-Filipinos.

“We had Grande and Buenas (supermarkets) but these did not have that moving staircase,” said 60-year-old Aquino, referring to the escalator.

Tagum had a central plaza, called Freedom Park, in front of the old municipal building in Barangay Poblacion, which attracted ordinary folk who spent idle time there.

In Cebu, Helen Relova Mantuhac, 68, said vast grasslands and wetlands largely ignored by the people of the sleepy town of Liloan and neighboring Consolacion in the northern part of the province had been transformed into commercial centers with two large shopping malls.

When her family needed anything in bulk, they traveled 22 kilometers to Cebu City, passing by these large vacant lands. Today, SM Consolacion, the biggest structure in town, stands there.

While commerce, spearheaded by property developers, grew in once barren lands in the provinces and expanded the local economy and infrastructure, it also altered the face of provincial town centers and consumer behavior.

In the City of San Fernando, the Gapan-San Fernando-Olongapo (GSO) Road was opened before Mt. Pinatubo erupted in June 1991, linking Pampanga’s provincial capital directly to the North Luzon Expressway and turning large tracts of sugarcane fields adjacent to the highway into busy commercial and transport hubs.

Nearby, to the east, SM Pampanga opened on Nov. 11, 2000, despite protests from small traders who feared losing their business in the old town center.

A year later, Robinsons Starmills opened as well.

SM juggernaut

In 2012, the SM juggernaut headed straight into the heart of the capital, forever changing the quaint and quiet old town center as SM San Fernando Downtown rose in the “poblacion.”

SHOPPING DISTRICT One of Tagum City’s “Big 3” shopping malls along a 4 kilometer stretch of the Butuan-Davao Highway —PHOTO COURTESY OF LEO TIMOGAN/TAGUM CITY INFORMATION OFFICE

Walter Mart, Vista Mall and Jumbo Jenra were built along MacArthur Highway midway between San Fernando and Angeles City.

In October this year, groundwork began on the third SM mall in the northern district of the city, Central Luzon’s capital with more than 50 regional agencies and at least 100 banks.

For retiree David, these malls symbolize “boom time” for his city of 306,000.

Theresa Mallari, president of Golden Group Gabay Puhunan Brotherhood Multi-Purpose Cooperative, said vendors and stall owners in the new public market had been competing with the shopping malls by lowering prices, concentrating on quality goods or personalizing their services, like making free deliveries.

Ivan Henares, president of the Heritage Conservation Society, said the mall culture had “driven Filipinos away from parks and public open spaces.”

“Parks raise the quality of life in our cities, providing healthy areas for rest and recreation. Our communities need lungs, not more malls,” said Henares, a native of San Fernando.

For artist Amiel Guanlao, shopping malls are like the “pavilions of the ancient world.”

“They serve to keep people happy,” he said. “What was lost in our modern times were the patios or plazas that cater to community narrative … . At the malls, you need to spend to stay inside.”

Guanlao observes an “alienation of the neighborhood, where an insertion of a mall in a city becomes a dislocation of the indigenous trading and business models.”

In the Visayas

From the 1970s up to early 2000s, Mantuhac, a recently widowed housewife, said people in her hometown of Consolacion relied on wet markets and sari-sari stores for basic necessities. They went to the big city only to watch movies or buy things they could not find in their public markets.

As shopping malls started to sprout in the cities of Mandaue and Cebu, Mantuhac said their air conditioning became a treat for families, especially the children.

She said several sari-sari stores were forced to close when SM opened its doors in Consolacion in 2012. The mall stole their customers, who preferred the all-in-one convenience these shopping centers offered.

Urban planner and architect Neil Andrew Menjares, coordinator of the architecture graduate program faculty of University of San Carlos in Cebu, said people would naturally prefer the shopping malls because they offered more choices.

“Unless the mom-and-pop stores have something unique to offer, they will eventually die once a mall comes to their town,” he said.

SOON TO RISE An aerial shot of Robinsons Place, now under construction in Naga City, Camarines Sur province —CONTRIBUTED PHOTO

Menjares, who has a master’s degree in urban and regional planning from the University of Iowa and has worked as design officer for a big shopping mall operator, said shopping malls had also evolved into transport hubs that provide “a constant stream of people” who shop, eat or just cool off.

“From a business point of view, it is attractive to store owners but it contributes to traffic congestion in surrounding areas,” he said.

In Mindanao

For Tagum’s local officials and urban planners, shopping malls are a gauge of economic development, and among the biggest employers, providing hundreds of jobs.

The city of 270,000 at the doorstep of Mindanao’s gold rush region has eight shopping malls. A ninth is expected to start operating next year, urban planner Lucia Damolo said.

In the next five to 10 years, as more business opportunities emerge, more investors in the shopping mall and retail businesses are expected to put up shop in Davao del Norte’s capital, said Damolo, a former planning chief of neighboring Compostela Valley province who now provides technical assistance to the Tagum government.

Profiting from Compostela Valley’s gold boom since the mid-1980s, the laid-back and insurgency-plagued city has risen to become a vibrant regional economic center.

“We are at a crossroads, so consumers, even from other areas, often drop by to buy or sell something in Tagum. Businesses, like shopping malls, find this place attractive,” Damolo said.

Along the Butuan City-Davao City segment of Asian Highway 26, three of Tagum’s biggest shopping malls, including the city’s first multilevel shopping center that gave it its first escalator, compete for Tagum’s shoppers.

One of the shopping malls gave the city its first 3D cinema.

In southern Luzon

In Naga City, the emergence of shopping malls encouraged homegrown businesses to branch out and flourish in friendly competition, said Alec Francis Altea Santos, chief of the city’s Arts, Culture and Tourism Office.

Naga has four shopping malls, with another one, expected to be the largest in the Bicol region, scheduled to open in 2018.

“Surprisingly, instead of feeling threatened by the arrival of malls in Naga, most homegrown businesses became more competitive and opened new branches inside the malls,” Santos said.

Shopping malls also spurred support businesses, such as food and beverage shops and transport terminals.

This clustering of businesses created commercial hubs around the city.

In Legazpi City, tourism officer Cristina Agapita Segui Pacres said the city’s 10 shopping malls had not diminished the attraction of the breezy seaside Legazpi Boulevard and its plazas.

The malls are mainly for shopping or business meetings, she said.

“Locals still love and appreciate the beauty of nature that they would go to Legazpi Boulevard for their morning walk and their spare time in the afternoon. The plazas are also perfect to watch local events,” Pacres said.

One good thing that resulted from the shopping mall invasion is the improvement of the facilities and management of the city’s public market, the Naga City People’s Mall, which houses around 2,000 stalls and shops.

Also, local plazas and parks in downtown Naga have been renovated to attract more foot traffic to the traditional commercial center.

“All of these initiatives were done not to compete directly with the malls but for local businesses offering tried and tested, and trusted products and services to complement the convenience offered by malls,” Santos said. —REPORTS FROM TONETTE OREJAS, FRINSTOM LIM, CRIS EVERT LATO, SHIENA BARRAMEDA, REY ANTHONY OSTRIA, MA. APRIL MIER AND MAR ARGUELLES