‘Lost Boy’ gets second chance

The small playground in Barangay Culiat in Quezon City where Rene Inso stood with some kids one Sunday morning is far from being Peter Pan’s Neverland, where a young tyke leads The Lost Boys—ill-behaved wanderers living dangerously but secretly longing for parental love.

In this very real world, the 17-year-old Inso was among the lost—a runaway at 13, a school dropout, a former drug user and a petty criminal who was jailed briefly when a youth rehab center failed to straighten him out.

Inso could easily be the subject that several lawmakers had in mind when they proposed to revert the minimum age of criminal liability from 15 to 9 years old.

Primary authors House Speaker Pantaleon Alvarez and Capiz Rep. Fredenil Castro said because minors could not be held criminally liable under the current law, they are being used as accomplices in crimes.

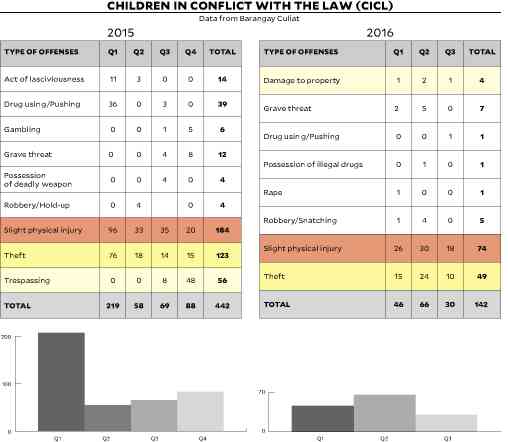

HOME FOR THE LOST The barangay Council for the Protection of Children in Brgy. Culiat, Quezon City, offers diversion program to children in conflict with law.

But Inso’s case is instructive and probably the best argument for second chances. Thanks to a barangay-based program in Quezon City, he has become a productive member of the community again. These days, he channels his energy as a volunteer for a local HIV awareness and prevention group, does theater work and offers free dance classes to high school students.

Article continues after this advertisementInso’s life story mirrors that of other children in conflict with the law

Article continues after this advertisement(CICL). According to the 2016 data from Regional Rehabilitation Centers for the youth under the Department of Social Welfare and Development, CICL usually come from poor families and households characterized by domestic violence, and have parents who are in conflict or are separated.

“The key is to provide (young offenders) appropriate community services, monitor their effectivity, establish a connection with their families and keep their parents accountable.” (Barangay chairman Vic Bernardo, Culiat, Quezon City)

Family dynamics

Inso grew up in a poor household where getting proper meals is an everyday struggle and a source of family disagreements. His parents don’t have regular jobs. His mother, 61, is an on-call laundry woman, while his father, 58, works as part-time carpenter.

“We always have to borrow money for food from our neighbors but because my parents have no permanent jobs, we can hardly pay them back. Our house doesn’t even have electricity,” Inso said.

His older siblings did not do any better. An older sister, Leore, is also jobless and a single parent to a 2-year-old boy. His brother, 26, was recently arrested on a drug-related case and is now in jail.

Such strained family dynamics stirred up feelings of deep anxiety in Inso, prompting him to run away from home and seek help from friends who turned out to be bad company.

They introduced him to “shabu” (methamphetamine hydrochloride), and soon had him turning to theft and other property crimes to support his drug habit.

Sent twice to Quezon City’s Molave Youth Home, a center for CICL, Inso said he was too wayward to be disciplined.

“I resisted the guards and fought with them. I was hostile even to the other Molave residents,” he recalled. The youth home staff decided to bring him to a Quezon city jail where he spent a week behind bars.

Fortunately for Inso, he became a beneficiary of the Barangay Council for the Protection of Children (BCPC) in Culiat, Quezon City.

Restorative justice

Guided by the principles of restorative justice, Culiat’s BCPC has created community-based programs that aim to bring back hope and dignity among children who got involved in crimes.

When the BCPC in Culiat, headed by Cristina “Nanay Bebang” Bernardino, village councilor and Vic Bernardo, village chief, heard Inso’s story, they realized he was one of many vulnerable children suffering from a sense of exclusion in a community supposed to provide them appropriate interventions.

“In 2013, Nanay Bebang visited me and said she wanted me to change for the better. It has been a partnership since then. They offered help and I fully, though gradually, accepted it,” Inso said.

As part of the barangay youth group under the Task Force on Youth Development, Inso was introduced to the Positive Discipline program that provides an alternative to corporal punishment through a partnership among parents, teachers, the BCPC, private organizations and the beneficiaries. Its core purpose is to uphold the rights of children, which include survival, protection, development and participation.

These rights are enshrined in Republic Act No. 9344, or the Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act of 2006.

“The key here is to provide CICL appropriate community services, monitor their effectivity, establish a connection with their families and keep their parents accountable,” said Bernardo. “We should not get tired of listening to and speaking with these children.”

Elitist

Bernardo said the Alvarez- and Castro-authored proposal to lower the age of criminal liability among minors is a product of an elitist world view.

“(These lawmakers) failed to understand that the root cause of this problem is extreme poverty. (Young offenders) need help from the community. They need understanding, not imprisonment,” he said.

Within a year after the barangay program was put in place, Bernardo said they observed a drop in the numbers of CICL and children at risk in their community.

Inso’s turnaround is illustrative. He is now a member of the Bata-Batuta Teatro, an impromptu, therapeutic theater led by community case managers from women’s and children’s desks.

“I then thought of returning to school to start anew, so I asked my former teacher at Project 6 Elementary School if I could enroll again, and she said yes,” he said.

Inso is also an active volunteer of the HIV YKAP program of the Quezon City Health Department and uses his monthly honorarium to help with his family’s expenses. “So we won’t fight over food anymore,” he said with a smile.

Inso’s current productive life contrasts sharply with those days when dangerous encounters with the police were a given. He recalled how he once planned to rob a house at Krus na Ligas, Quezon City, only to find himself facing a gun. The house owner turned out to be a cop. He managed to escape.

At 14, Inso had a child with his girlfriend, both of whom he never saw again—on orders of her father, also a policeman.

Dreaming of police work

“But I’ve always wanted to be a policeman,” he said. “I want to help minimize criminality in our country. I also feel that if I were one of them, I’d be able to do something about the extrajudicial killings. Those are lives. That could have been me, or any of us,” he said, referring to the spate of killings of alleged drug users in the government’s total war on illegal drugs.

Asked about his brief time in prison, Inso said he knows he could never have turned his life around if he had spent more time behind bars.

“There’s nothing there for children like me. We could even get killed,” he said.

Thanks to the second chance given him by Nanay Bebang and the barangay council, Inso believes he can now correct his mistakes and start dreaming again.

Could he be a chef? he mused. That could mean his family would never go hungry again, he added.

“Now that I’ve changed for the better, I’ll keep sharing my story with others in similar situations. They deserve our help,” said Inso who, like Peter Pan, now dreams of flying.