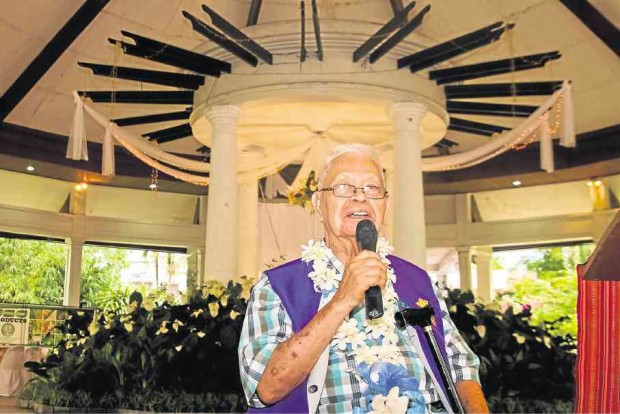

LOS BAÑOS, LAGUNA—At 88, Serapion Metilla is as sharp as his trimming shears.

A large part of his home in Novaliches, Quezon City, is planted with greens of various kinds, perhaps the secret to his long and well-lived life.

“When I was still small, my older sister was very fond of flowers. I grew fond of them too, planting and watering them,” Metilla said.

His fascination with flora would be his ticket to becoming one of the icons of Philippine horticulture. He later founded prestigious horticultural organizations, among them the Philippine Bonsai Society, the Cactus and Succulent Society, and the Ikenobo Ikebana Society of Davao.

THORNY AND BEAUTIFUL Cacti of various colors at the recent Los Baños Flower and Garden Show. —KIMMY BARAOIDAN

For two terms, Metilla served as president of the Ikenobo Ikebana Society of Manila No. 67. He is also an honorary member of the Philippine Orchid Society, the Philippine Horticultural Society Inc., and the Bonsai and Suiseki Alliance of the Philippines Inc.

Teacher

A child of a landless couple from Camotes Island in the Visayas, Metilla’s family migrated to Davao City under a government land program. After high school, Metilla was called in by the government to teach grade school as an “emergency teacher” on Sarangani Island.

He taught for two years and when professional teachers from Luzon and the Visayas came in, Metilla went on to pursue a teaching career. He obtained an Elementary Teacher’s Certificate and moved to Manila in 1956 to teach at Kamuning Elementary School in Quezon City for the next 26 years.

It was around the 1960s when Metilla came across Ikebana.

“There was a [garden] show at the Luneta [park]. I got in because [entrance] was free,” he said.

But to be a member of the Ikebana International, Metilla had to pay an annual P10 fee, which he could not afford out of his monthly teaching salary of P140.

Metilla must really have the talent for it, anyway. He volunteered his services to the group in exchange for attending several workshops and training sessions. Members liked his work so much that his fees were eventually waived.

Ikebana is the traditional Japanese art of flower arrangement, dating back to the 7th century. But Metilla said the art originated from Buddhist monks in China and India who gathered flowers and displayed them on the altar. The idea spread to Japan and was fine-tuned by Japanese artists.

“It’s flower arrangement, but not all flower arrangements can be called Ikebana,” Metilla said.

The art, he said, follows certain principles to achieve a minimalist yet elegant outcome. The classical style, called Shoka, requires that only living plant materials would be used.

Over the years, Ikebana artists began practicing Jiyuka or the free style. Here, dried materials like wires and balloons are used as accessories.

Another style is Rikka, which is a “nine-part” composition that blends in plants of various kinds and sizes to resemble a “community landscape” of water and soil.

“Very few can do [Rikka]. You have to learn how to choose materials that suit [the style] and blend them all in harmony,” he said.

The garden show at the University of the Philippines Los Baños campus in October featured landscape designs and ornamental plants. —CHRIS QUINTANA

Metilla eventually retired from formal education but never stopped learning and teaching. At the time, he started with bonsai gardening, then popular among the country’s elite. He also specialized in terrarium, the art of putting plants inside glass containers.

In 1973, Metilla organized the Philippine Bonsai Society.

Earning his reputation in plant arts, Metilla was invited by former First Lady Imelda Marcos to head the Aurora Garden in the early 1970s. “I conducted workshops on bonsai gardening and flower arrangements for the Blue Ladies,” Metilla recalled. They were the wives of politicians and top businessmen in the country.

Unlike his plants, Metilla’s experience working with Marcos did not blossom into something pretty. After a couple of years, he was fired and replaced by a relative of one of the women whom he had trained.

Without a single centavo as separation pay, Metilla said he considers himself “a victim of the Marcoses.”

“I even thought of joining the NPA (New People’s Army), but I just tried to forget all about it,” he said.

Bonsai

Like Ikebana, bonsai was originally a Chinese concept, although it was perfected by and credited to the Japanese, Metilla said. Bonsai, a Japanese term, means “potted plant.”

“It was started by a Chinese Buddhist monk who planted … on a rock with very little soil. The result was the plant was dwarfed,” Metilla said. Bonsai gardening then spread across the United States through American soldiers who were assigned in Japan after the war.

In the Philippines, Metilla said bonsai gardening was present even before the Spanish period. He cited chapters from the book, “Relacion de las Islas Filipinas,” of Fr. Pedro Chirino that mentioned dwarfed Balete trees of the Chinese in Binondo, Manila.

But bonsai gardening as a hobby bloomed only in the 1980s, Metilla said.

“Maybe it has something to do with our custom. Filipinos don’t really see the benefit [from gardening] unless they grow something edible [or get something in return]. It was only after the liberation [from the Japanese] that we were really educated about the arts,” he said.

Art for everyone

Metilla used to supply ornamental plants to shopping malls and, in 1980, opened his own brand, Mett’s plant art, with at least three stores in Quezon City.

On the side, he continued conducting workshops all over the country on flower arrangement. Metilla holds the rank of Ikebana Professor 14, after earning credits through workshops abroad recognized by the international club.

The popular notion of Ikebana is “sosyal,” something that only the well-off can afford and sustain, Metilla said.

But anybody, as long as they want to learn and hone creativity, can delve into the arts, he said.

Most Filipino bonsai collectors, for instance, love the art but just do not have the time for the meticulous hobby.

He said they usually hire plant artists, for a fee of P1,000 a day, to trim, repot or do the wiring to make sure the stems grow toward the right direction.

Even now that he finds it hard to stand straight, Metilla would still accept invitations to garden shows and share his skills to younger plant artists.

In October, Metilla was speaker at the annual garden show of the Los Baños Horticultural Society Inc. in Laguna. This year’s show, held at the University of the Philippines Los Baños, featured rare plant and flower species for garden weddings.

Metilla never married but he is never alone in the company of his family and plants. But to say until when he intends to practice his craft, he said: “It will go on, till death do us part.”