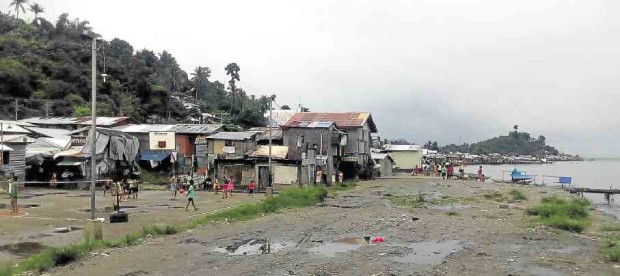

Makeshift houses remain in Barangay 66, Paseo de Legaspi District in Tacloban City, which had been declared a no-build zone after Supertyphoon “Yolanda” (international name: “Haiyan”) struck on Nov. 8, 2013. —JOEY GABIETA

First of two parts

TACLOBAN CITY—While they now live in a structure she calls home, Armen Jane Cabias still longs to settle in a permanent house, away from the dangers that natural calamities, like storms, bring.

Armen Jane, 23, lives in a house made of light materials 400 meters from Cancabato Bay, where a wave that reached 20 feet high rose before sweeping everything in its path and killing 100 villagers at the height of Supertyphoon “Yolanda” (international name: “Haiyan”) on Nov. 8, 2013.

She, her husband Felipe and daughter Argail Jane all survived, but the flood swept away their house in Sitio Mahusay of Barangay 88 in San Jose District.

They, along with 47 other families, now live in a housing project donated by the Urban Poor Associates (UPA), a non-government organization.

“While we are happy that we now have a house through the help of UPA, we still want to be (relocated) at a permanent settlement just like the others,” Cabias said.

The housing project is on a private lot which means the typhoon survivors could be removed any time.

No-build zones

The city government of Tacloban prohibited the construction of houses near or 50 meters from the shore, declaring these areas as no-build zones.

But due to the delay in construction of permanent houses for families whose houses were destroyed or are located in danger zones, houses continued to sprout in no-build areas, where the absence of electricity or water has not deterred the construction of houses.

As of October, only more than 2,000 families have been resettled in permanent houses.

Sonny Ciriaco, a fisherman in the island barangay of Malangabang in Concepcion town in Iloilo, is also waiting for a permanent housing site.

He is among those who are living near the coastline which was also declared a no-build zone.

Villagers like him have rebuilt or repaired their houses swept by 20-foot-high waves during the supertyphoon. But they still worry if a disaster strikes again.

“We have recovered. But the risk is still there because we are still living near the shoreline,” he told the Inquirer.

Island villages

Concepcion Mayor Millard Villanueva said officials have identified relocation sites on major islands and the mainland.

But residents on the islets do not have areas to transfer to except on the mainland.

Eleven of the town’s 25 villages are island-barangays where more than half of the town’s population of about 50,000 live.

“In the small islands, it’s either the coastline or the mountains that are uninhabitable,” Villanueva said.

The municipality, through the National Housing Authority, seeks to build 3,000 housing units on the mainland and 1,300 houses on the islands but none has been completed three years after the typhoon survivors lost their houses.

The first 400 units on the mainland would be turned over in December.

Sources of livelihood

Villanueva said blamed the delay on contractors and the failure of the government to release funds for the project.

Nongovernment organizations and foundations, however, have turned over hundreds of houses in the municipality.

In Roxas City in Capiz province, hundreds of families along the coastline are also still living in no-build zones.

Roxas City Mayor Alan Celino said most of the families in nine coastal barangays worst hit by the supertyphoon have refused to transfer to a relocation site some six kilometers from the city center.

“They want to be near the coastline because of their livelihood,” Celino said.

Better prepared

Local officials said they are now better prepared to address major natural calamities like Yolanda.

Villanueva said officials have instituted contingency plans, enhanced the training of responders and other disaster-preparedness measures.

The municipality is also building a two-story evacuation center costing P10 million which can accommodate 1,500 evacuees.

But the Panay Center for Disaster Response (PCDR), a nongovernment organization providing assistance and service on disaster preparedness, relief operations and rehabilitation programs, said disaster preparedness efforts would be put to waste unless communities in danger zones are relocated near their sources of livelihood.

“Many are still living in danger zones because there is inadequate relocation. Some relocation sites are too far, inaccessible or do not provide alternative means of livelihood,” said Armie Almiro, PCDR executive director.

“Communities there may have early warning systems, hazard maps and disaster preparedness committees but they remain at risk,” Almiro said.

(To be continued)