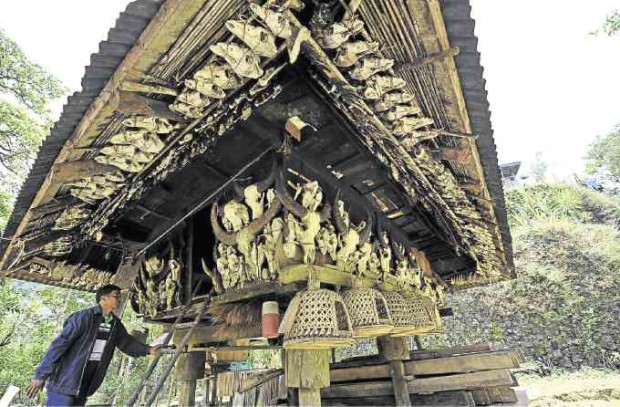

HUT AND BONESA unique feature of this “ba-le” is a collection of animal skulls. Below, tourists can spend a day in this hut for P1,500. Photos by EV Espiritu

BANAUE, IFUGAO—Tourists who want to “live as the natives do” may find themselves pounding rice or hauling stones to repair the walls of this town’s famous terraces.

Then they are invited to sleep in authentic Ifugao huts lined with the bones of animals and—surprise—what appear to be human skulls.

It’s part of the allure of the community’s homestay program, and local and foreign guests are immediately comforted by families that those relics are indeed authentic skulls which they inherited from their ancestors.

The program gathers families who provide living arrangements for visitors for a fee. The hosts show guests how they live, think, work and appreciate their environment.

Virtual museums

Ba-le (native huts) are also virtual museums, which often contain collections of “trophies,” such as animal bones and human skulls that often intrigue outsiders.

The animal bones are at times a testament to the number of animals sacrificed by a kadangyan

(a rich man in the community who owns vast landholdings

or terraced farms). There are bones representing the family’s hablag (animals contributed for community rituals).

Many human skulls, referred to as changit or hangit, are artifacts from ancient headhunting expeditions, which were undertaken by communities against enemy tribes.

“Bul-ul” of various sizes and shapes are kept in a rice granary. Below is the postcard-perfect view of the rice terraces of Banaue.

Good storytellers

The Ifugao hosts are good storytellers, providing tales about their family histories. Some are great adventures, but occasionally, the accounts paint a picture of life-changing horrors.

“My father used to tell me some of the skulls on display in our house belonged to invading Japanese soldiers, who were decapitated by villagers for raping their women and for burning many ba-le during World War II,” said Noel Balinga, who owns Hiwang Native House Inn and Viewdeck at Sitio Hiwang in Barangay Viewpoint.

“This was a granary and ritual house,” he said, showing a bul-ul (statuette depicting a mythical rice granary guardian) and skulls of sacrificial animals like carabaos, pigs and chickens that adorn the walls.

War’s brutality

The human skulls were meant to show the brutality of the war in Ifugao, where Japanese Imperial Army commander, Gen. Tomoyuki Yamashita, made his last stand before surrendering in 1945 to effectively end World War II in the Pacific.

“Hundreds of orphaned children in Ifugao were cared for by the Belgian Missionary of St. Joseph in Kiangan, after World War II. My father was a spy for the guerrillas so he was killed,” said Agapita Tindaan, 73, a retired grade school teacher.

“As a child, we used to live in Barangay Nagacadan. I don’t know what happened to my mother. All I remember was that an uncle, who was a mumbaki (native shaman), took care of me before leaving me with the Belgian missionaries,” Tindaan said.

Alex Ordillo, of Barangay Gohang, said the tomb of his parents lies next to their ba-le, but it had not disturbed any of his guests.

But some admit that sleeping near the skulls makes them shake from fear, he said. —WITH A REPORT FROM EV ESPIRITU