He saves seashells by the seashore

MINALABAC, Camarines Sur—Leovigildo Basmayor Sr.’s fascination with seashells started during World War II. Then 6 years old, he fiercely protected his first collection as his family was leaving their home to escape Japanese troops advancing to Camarines Sur province.

“I put them (seashells) in a jar, then buried it in our yard before we left,” Basmayor, now 84, says. “When we returned years later, I dug them up and they were all safe.”

From an array of seashells laid out before him for inspection, he picks a favorite, a peach shell called Golden Cowrie (Lyncina aurantium), which he and his son Gil, a former Minalabac town mayor, found in Sorsogon province.

The items represent just a fraction of his collection kept at Bicol Shell Museum in the coastal village of Bagolatao in Minalabac. Each one is properly labeled with common and scientific names that Basmayor himself had written.

Lettered conch shell

Article continues after this advertisementFrom a jar, his trove has grown to over 4,000 species picked from all around the Philippines, a testament to his life as a marine biologist, educator, science researcher, taxonomist and nature lover.

Article continues after this advertisementAmong these are specimens of conch shells, including 10 of the most venomous types in the country, and the famous lettered conch shell (Conus litteratus) that bears Roman numerals, Hindu-Arabic letters, and even English and Filipino words.

Basmayor also keeps a single specimen of the smallest cypraea seashell, which measures about 2 centimeters.

At the museum, capiz shells shine beside a chambered nautilus shell (Nautilus pompilius), paper nautilus shells (Argonauta argo) and assorted abalone kept in glass cases. There are giant clam shells (Tridacna gigas) from Palawan province and amber pen shells (Pinna carnea) from Sorsogon.

As a boy, Basmayor spent his idle time on the beach of Bagolatao, where his fascination for marine life and seashells started.

Collector

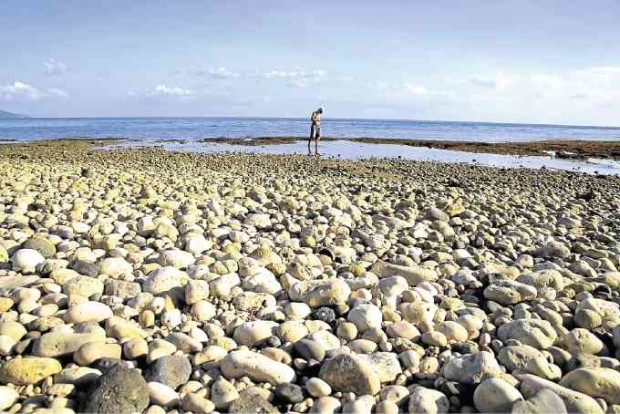

Basmayor started gathering seashells from the pebbled shores of Minalabac while growing up in Barangay Salingogon. His family was among the first settlers there.

“Back then, I was the only child here. My hobby was digging and holding earth,” he says.

With no other children

to play with, Basmayor took

interest in everything about

the sea in the town’s unspoiled

and almost uninhabited surroundings.

“I collected seashells because they are unlike most things people collect. Unlike collectibles, such as stamps, seashells never fade or grow old. Every day, you learn new things from collecting seashells,” he says.

He also keeps sand in vials, scooped from every beach he visits. A section of the museum features preserved starfish, seahorse and other marine creatures.

Basmayor pursued a marine biology course at University of Nueva Caceres (UNC) in Naga City. In exchange for a scholarship grant, he worked as the university science department’s collector and taxonomist. He found and preserved hundreds of insects, butterflies, animals and seashells displayed in UNC’s museum of natural sciences, the first in the Bicol region.

He studied for his masteral degree at the University of the Philippines in Diliman, Quezon City, and took on his first projects as a marine biologist there.

“There was one time that Papa ‘lived’ under the sea,” his son says. “He was underwater manning a sort of checkpoint in different locations in the Philippines where he observed, recorded and counted every fish that crossed his line at specific times.”

Educational tour

Citing his father’s fascination with marine creatures, Gil thought of building a museum to preserve what remains of his life’s work. On a hilltop overlooking the shores of the family-owned White Pebbles beach, Bicol Shell Museum opened in March 2014.

Basmayor retired 17 years ago as a science teacher to generations of students in Bicol University in Legazpi City, Albay province.

In 1970, when Typhoon “Sening” (international name: Joan) ravaged Bicol, Basmayor lost half of his collection. The family house in Salingogon crumbled, sending debris crashing on boxes of seashells.

Basmayor believes that his collection is the best instrument in teaching visitors, regardless of age, the wonders of science and marine life.

The family resort has been transformed into an educational tourism spot, where people enjoy the beach and learn new things at the museum.

“It’s time that they learn to appreciate the sea more than as a place to swim in,” Basmayor says. “I want them to know that we have the richest sea; the best in the world.”

Just 17.7 kilometers away from Naga City, the village of Bagolatao is accessible from the city via the Cararayan-San Isidro Road after a one-hour jeepney ride. Fare is P40 per person. This road is rough and becomes muddy during rainy days.

The only passenger jeepney plying Bagolatao leaves the Northbound Terminal in Naga at 10 a.m. daily and returns to the city at 6 a.m. the next day.

Tourists going to Bagolatao beach may also rent jeepneys. A one-way trip costs P1,500.