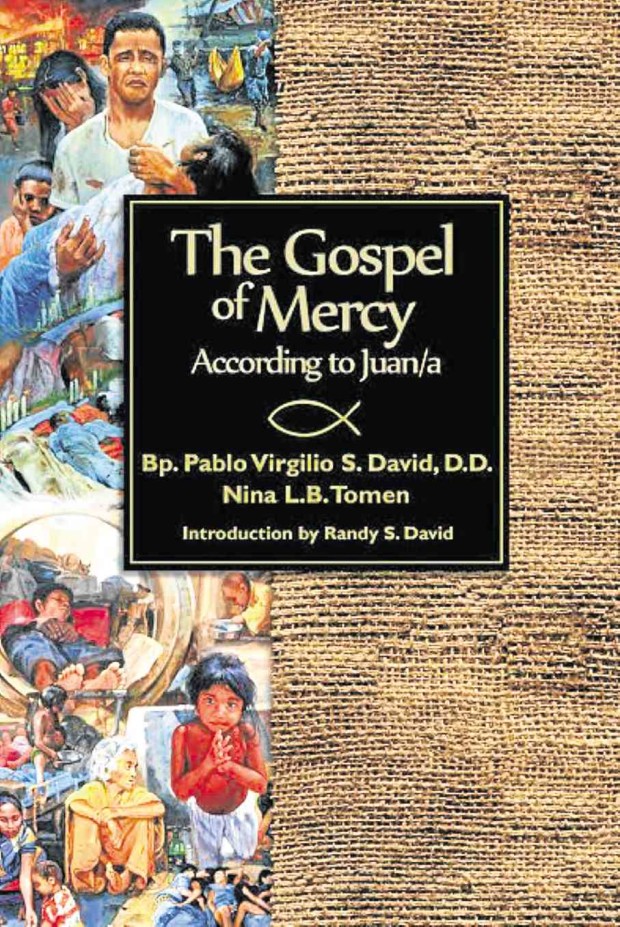

Stories about mercy, the kind that Filipinos share and express, are being read by Pope Francis and others for sure. These are in the book, “The Gospel of Mercy According to Juan and Juana,” which Bishop Pablo Virgilio David, one of the writers, handed to Pope Francis at St. Peter’s Square in the Vatican City on Sept. 7.

Sharing the joy of giving the book, David said on Facebook: “[Pope Francis’] eyes lit up with delight when I gave him what I called “nuestra contribucion humilde al Jubileo de la Misericordia, de una perspectiva Filipina” (our humble contribution to the Jubilee of Mercy, from the Filipino perspective).”

Learning that the book had been translated from English into Spanish so “he could really read and enjoy it,” the Pope exclaimed, “No kidding!”

The Spanish translation was done by Fr. Salvador M.T. Curutchet, an Argentinian missionary stationed in the Diocese of Caloocan, and Rene Angelo Prado of the Ateneo de Manila University.

The idea for the book project cropped up in July 2015 when Nina L.B. Tomen, David’s co-writer, sat in the bishop’s Hermeneutics class when the topic shifted to the Misericordiae Vultus (Bull of Indiction on the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy). Pope Francis tied mercy to poverty.

Gentle voice

Prodded by what she called a “gentle voice,” Tomen texted David and Fr. Albert Alejo, S.J., urging them to write a book on mercy.

Eight months later, Tomen and David wrote 27 stories and five essays. Alejo was busy with the “lumad,” farmers, workers and students so he was not able to contribute stories to the

collection.

“This book contains real stories of real people. More than mere characters, we are co-sojourners in the pilgrimage back to Eden,” Tomen wrote.

David said there is no one word for mercy in the Filipino psyche. There are “awa” and “habag,” with David translating these to be pity and the experience itself of being moved from within, respectively.

Mercy also takes the form of action, which starts in “malasakit” (compassion) to “magmalasakit” or “pagmamalasakit”(response meant to ease the misery of a person).

Then there are “patawad” (to forgive) and “pagpupuno” (accepting shortcoming). “Mercy as the abounding graciousness of God’s response to human sinfulness is what the Filipino ‘kagandahang-loob (pagmamagandang-loob)’ represents,” David said.

The nuances of these forms of mercy are in the stories. Published by St. Paul Philippines, the book got good reviews.

Fr. Catalino Arevalo, S.J., emeritus professor of theology, called the book “perhaps the best Philippine ‘byproduct/blessing’ of the Year

of Mercy. ”

“This is a book which without doubt will do much good and be of much service; of much use for classroom and study-groups also. (Teachers, alerted!),” Arevalo added.

Manila Archbishop Luis Antonio Cardinal Tagle considered the book “God’s gift of mercy to us on this Jubilee.”

“These two scholars, who are both most capable of presenting theories about mercy, opted to tell stories—and gripping stories at that. By this choice they remind us that generations of people have seen the merciful face of God in God’s involvement in their stories. Reading the stories recounted by Bishop Ambo and Nina I felt they were sharing their friends with me,” Tagle said.