QC keeps database of druggies, eyes more rehab centers

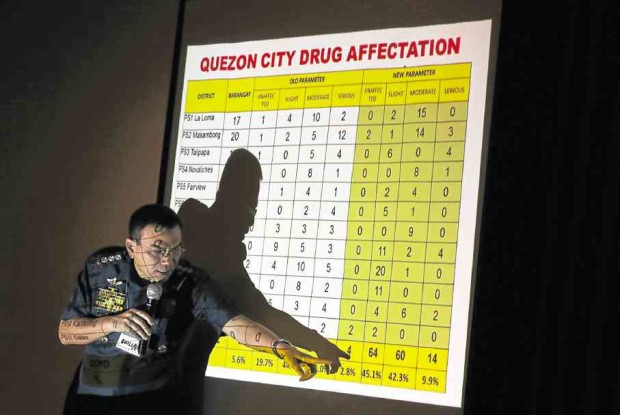

NARCO-NUMBERS QCPD director, Senior Supt. Guillermo Eleazar, makes a presentation during the Quezon City drug summit on Thursday. NIÑO JESUS ORBETA

As the death toll in the government’s war on narcotics rises to over 3,000 nationwide, the Quezon City government is making its own count—not of slain suspects but of drug dependents who need saving.

Speaking on Thursday at the city’s first Stakeholders Summit on Drug Abuse Prevention and Education, Vice Mayor Joy Belmonte said City Hall is boosting its drug rehabilitation program with the setup of a database for the thousands of drug users who had surrendered to the police under the “Oplan Tokhang” campaign.

‘Know them first’

“Before we can address the users’ needs, we should first know who these people are,” Belmonte told the multisectoral gathering that included the police, medical practitioners, religious groups, teachers and students.

Formally called the Integrated Drug Abuse Profiling System (IDAPS), the database was launched in July as the first of its kind in the country, said Belmonte, who also chairs the Anti-Drug Abuse Advisory Council.

Article continues after this advertisementMaintained by the Barangay Anti-Drug Abuse Council, it contains the profiles of Tokhang surrenderers grouped according to village, stating their names, addresses, sex, employment status and drug of choice.

Article continues after this advertisement“This is a way to monitor them. This database is shared with the police, the local government and even the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency,” the vice mayor explained.

The Quezon City Police District put the number of surrenderers in the city at 8,421 as of Thursday. Only 18 percent of the total have so far been entered into IDAPS.

In an interview, Belmonte said 142 computers were donated to the city’s barangays, complete with biometric systems and cameras, for a more efficient data gathering and processing. The equipment were procured using excess funds from the mayoral term of her father and former Speaker Feliciano Belmonte.

Two persons are assigned per barangay to handle the concerns of drug surrenderers.

“In these addiction cases, we’ve seen that only around 20 percent need to be institutionalized,” Belmonte noted.

Yet local drug treatment centers are now bursting at the seams, hence there is a need to strengthen community-based rehabilitation programs, she said. “It begins with the family but also needs to involve health, educational and spiritual workers.”

The city-run center known as Tahanan, for example, was designed for only 150 people but now houses around 300.

City Hall hopes to construct six drug education centers catering to out-of-school youths and other vulnerable sectors. The first of such centers is now rising in the Batasan area and is expected to be operational by November.