The fatal shooting of Fr. Fausto Tentorio of the Pontifical Institute for Foreign Missions (PIME) in the early morning of Oct. 17 is one more violent incident marring Arakan Valley, a place of immense beauty and natural wealth.

Traversing fertile land from Cotabato to the boundaries of Bukidnon and Davao City, Arakan and its adjacent areas that include sloping hills and steep mountains have contributed to making Mindanao the fabled Land of Promise for migrant settlers and wealth-seekers.

The Manobo had lived since time immemorial in Arakan and its lush forests. They worshiped Manama, their supreme deity. Their “walian” (shamans) had “abyan” (guardian spirits) and offered rituals to the spirit world. Their “bagani” (warriors) fought battles to defend their communities, which is why the Manobo honor their “pangayaw” (war-waging) tradition.

Across this landscape were signposts to remind them of important events in the lives of their heroes. These events are incorporated in their epic “Ulahingan,” which continues to be chanted today, and which depicts a brave people resisting any attempt to dominate them.

But while the Manobo were fierce, harmony and mutuality were maintained in the tribe through customs and laws. The precolonial period allowed them to establish their sense of identity vis-à-vis the neighboring tribes.

It was in the 1950s when the colonization of the Manobo life-world drastically changed the life of the Lumad. Fr. Fausto Tentorio, Italian, was not the first foreigner to penetrate the interior of Central Mindanao.

Cattle ranching

In the 1920s—half a century before Father Fausto arrived, at the very height of the US occupation—Americans encroached on the adjacent province of Bukidnon. They saw its tremendous economic potential, specifically in cattle ranching.

The ranches expanded, so that there were more than 60,000 head of cattle in Bukidnon by the end of the 1930s. More ranchers came and pushed into vast tracts of land, gradually displacing the Bukidnon, Talaandig, Higaonon and Matigsalug from their ancestral domain.

Eventually, the ranchers crossed the boundary to Cotabato. One of them was Augusto Gana, a Tagalog settler who at one time was the mayor of the small town of Kidapawan. Armed with a pastoral lease agreement, he took over more than 1,000 hectares of land in Arakan for his ranch.

Gana sought the approval of the Manobo chieftains through agreements, which he did not fulfill. Eventually, chieftain after chieftain (mostly of the Ansabu clan) waged various pangayaw against him.

In retaliation, Gana expelled the Manobo from their land, burned their houses, destroyed their crops, and killed their leaders.

The pangayaw persisted throughout martial law until Manda Elizalde of Panamin found a way to get the chieftains to lay down their arms.

But not for long. More resistance flared, although it was more in terms of legal battles than armed uprisings.

More settlers

In the 1950s, peasants began arriving in Arakan hoping to own a piece of land they could till. They sought ways to get the Manobo to allow them to take over small plots in exchange for sardines, cigarettes and other goods from the lowlands.

An increasing number of the Manobo started retreating to the hinterlands. But they soon found that there were no more forests, and many were forced to live in peaceful coexistence with the settlers.

As more Christian Ilonggo reached Arakan, religious congregations sent missionaries to minister to them. The first to reach Arakan were members of the Oblates of Mary Immaculate, but by the 1980s they had all moved out of Arakan.

There were PIME missionaries who came to the Philippines before Father Fausto. He himself arrived in 1978 and went straight to learn Cebuano-Bisaya at Maryknoll Language School in Davao City. (Later he would learn Ilonggo.)

I taught Philippine culture in this school, and that’s where I met the PIME missionaries including Father Fausto. I was then the executive secretary of the Mindanao-Sulu Pastoral Conference Secretariat, which was the bishops’ arm to promote the Basic Christian Communities (BCCs) as well as projects for the farmers, fisherfolk, workers, urban poor and Lumad in the area.

Hippie priest

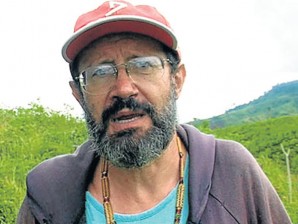

One was struck by Father Fausto, fondly called Father Pops. With his sharp eyes, shoulder-length hair, and simple wardrobe (T-shirt, faded jeans, rubber slippers), he was a hippie Jesus look-alike.

One was easily drawn to him. He was gentle, soft-spoken, unobtrusive, and insisted on staying in the background. He worked hard on the language and was very interested to know about the Philippines, particularly Mindanao, the people’s culture, the evils of martial rule, and the people’s resistance.

At first meeting, one knew he was a progressive churchman with militant views on justice and the burning social issues of the day. But he was no rabble-rouser; he did not make radical speeches and fiery sermons. He listened intently to what people had to say and was very supportive of lay people.

He was a good team player.

His first assignment was in the PIME parish in Ayala just outside Zamboanga City. Later he was assigned to the Diocese of Kidapawan, first in the parish of Columbio in Sultan Kudarat.

In the early 1980s he was sent to Arakan.

At that time the valley was seething with the Manobo’s frustration as the arable land in their control quickly dwindled. Life was not rosy either for most of the migrant settlers, although they were a little better off than the Lumad.

But businessmen from the lowlands and local government bureaucrats aligned with the Marcos dictatorship—all well-protected by the military—continued to find ways to grab more fertile land.

The national democratic movement became attractive to both the Lumad and the peasants as it promised liberation from their oppression. Cadres of the Communist Party of the Philippines and its armed wing, the New People’s Army, found their way into Arakan and found sanctuary there.

Empowerment

Father Fausto initially assisted his confreres in building and strengthening BCCs, but soon decided to work full-time for the Manobo as part of the Tribal Filipino Apostolate.

He stayed in this apostolate for the rest of his life along with another confrere, Fr. Peter Geremia of the PIME. The Ilonggo Christians were not too pleased with this; they could not see why he favored the interests of the Manobo over theirs.

Father Fausto decided to address the plight of the Manobo who, like many of the Lumad in Mindanao, are the most neglected among our people in terms of government services and even the ministrations of the churches.

He trained Ilonggo staff set up literacy classes, health centers, and farm and other livelihood projects in order to provide the Manobo the skills they needed to improve their lives.

Hundreds of Manobo families benefited from these projects.

But the most pressing task was to stop the encroachment of outsiders on the remaining Manobo ancestral domain.

With the Manobo having little political power, Father Fausto and his staff realized that empowerment was imperative. Thus the massive organizing work in all the Manobo settlements, which led to the birth of the Manobo Lumadnong Panaghiusa (Malupa).

The powers-that-be soon took notice of the fast strengthening Malupa. Through the sheer force of unity and backed by the social capital of the Church, the Manobo struggled for self-determination. There were skirmishes with the military and its militia, but they were somehow able to advance their interests.

Father Fausto never took center stage in all these. With the Manobo empowered to take leadership, he took on the role of inspiring, supporting and affirming them.

At risk

But the PIME missionaries experienced harassment, and eventually two of them were shot dead for their commitment to the poor of Mindanao—Fr. Tullio Favali in Cotabato on April 11, 1985, and Fr. Salvador Carzedda in Zamboanga on March 20, 1992.

Father Fausto knew that he, too, was at risk. The danger became quite clear in 2003, when members of an anticommunist paramilitary group attempted to kill him while he was visiting a remote barangay in Kitaotao, Bukidnon.

Clear choice

Father Fausto made a clear choice. Like the Man from Nazareth whom he followed all the way to Arakan, he chose to be on the side of the most abandoned.

I knew him for almost four decades. I have the audacity to claim that he was my friend. He was always delighted whenever I visited him and spent time in Arakan.

In the chilly nights, he bared his soul as we talked about our hopes and dreams, struggles and frustrations.

He was fearless. Not once, not even in the worst of times, did I ever note fear in his heart. He lived simply in the company of the Manobo, at peace in the land that he loved.

With his death, Father Fausto has become a martyr. In the old days, a martyr was immediately declared a saint. But to label him a saint would surely make him laugh!

(Editor’s Note: The author, a Redemptorist brother, grew up in the 1950s in Digos, Davao del Sur, where settlers like his family coexisted with Lumad and Moros. He holds a Ph.D. in Philippine studies from the University of the Philippines in Diliman, Quezon City, and is the author of the book “Manobo Dreams in Arakan: A People’s Struggle to Keep their Homeland” (2011). The book is a comprehensive account of the struggle of the Manobo in Arakan Valley to keep their ancestral lands and, in the process, assert their cultural identity.)