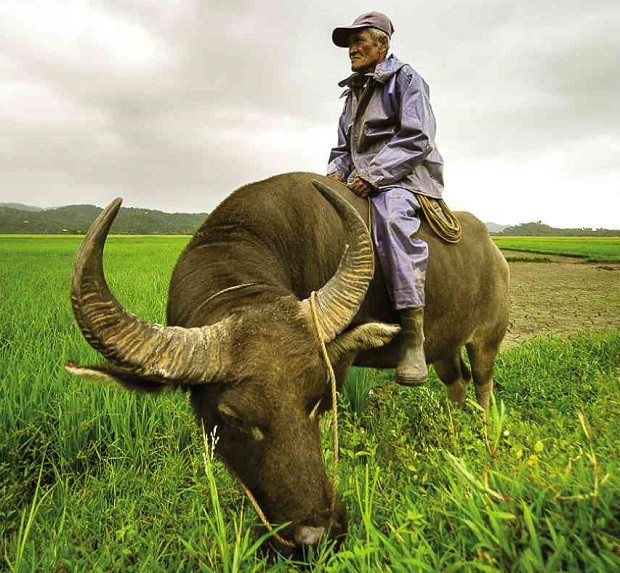

A carabao in Cagayan grazes accompanied by its owner. In the US, farm animals have been found to help farmers beyond the field. ResearcherS have found microbes from farm animals help boost the immune system of farmers’ children preventing allergies such as asthma. INQUIRER FILE

MIAMI, United States — Children who grow up on traditional Amish farms in the United States are largely protected from asthma because their immune systems are bolstered by close contact with farm animals’ microbes, researchers said Wednesday.

The study in the August 4 edition of the New England Journal of Medicine compared two similar communities — the Amish of Indiana and the Hutterites of South Dakota — which have different methods of farming.

The Amish, known for their simple living and dislike of modern technology, live on single-family dairy farms and use horses for fieldwork and transport.

The Hutterites use modern, industrialized farm machinery to work their larger, communal farms, which distances them somewhat from the daily exposure to animals.

Otherwise, many aspects of the two groups are similar. They have similar genetic ancestry, having come from Central European immigrants, and follow a traditional Germanic farming diet.

They also drink raw milk, get their children vaccinated, breastfeed their babies and do not allow indoor pets.

But their asthma rates are vastly different.

About five percent of Amish schoolchildren have asthma — about half the US average.

Meanwhile, Hutterite children have an unusually high prevalence of asthma — 21.3 percent — said the study.

“Over a decade ago, our colleague Erika von Mutius discovered that growing up on a farm can protect against asthma,” said study co-author Carole Ober, professor and chairman of human genetics at the University of Chicago.

“Our new study, building on her work, now shows that it’s not simply farming, and has narrowed in on what the specific protection might be.”

‘Richer’ home dust

Researchers found that the difference came down to the kind of dust inside their homes.

Dust in Amish homes was “much richer in microbial products,” said the study.

“Neither the Amish nor the Hutterites have dirty homes,” explained Ober.

“Both are tidy. The Amish barns, however, are much closer to their homes. Their children run in and out of them, often barefoot, all day long. There’s no obvious dirt in the Amish homes, no lapse of cleanliness. It’s just in the air, and in the dust.”

This dust engages the children’s innate immune system to fight off asthma, the study found.

Blood tests done on 30 Amish children — aged seven to 14 — and 30 Hutterite children of the same age range showed the Amish had more blood cells crucial to fighting infections, known as neutrophils.

The Amish also had fewer blood cells that promote allergic inflammation, known as eosinophils.

When researchers exposed lab mice to the Amish house dust, they found the rodents were protected against asthma-like responses to allergens. Similar experiments with the Hutterite house dust conveyed no protection.

According to Sherry Farzan, a doctor in the department of medicine and pediatrics, allergy and immunology at Northwell Health in New York, the paper offers more evidence to back up what has been called the “hygiene hypothesis,” which suggests that a lack of early microbial exposure increases the risk of allergy.

“Exposure to a rich microbiome early in life is protective of allergy and asthma, and seems to be due to the anti-inflammatory modulatory activity of this exposure,” said Farzan, who was not involved in the study.

For co-author Erika von Mutius, professor at the Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital in Munich, Germany, the next step is to find a way to apply this knowledge to help future generations of children.

“We hope that our findings will allow the identification of relevant substances that will lead to completely novel strategies to prevent asthma and allergy,” she said.

Agence France-Presse