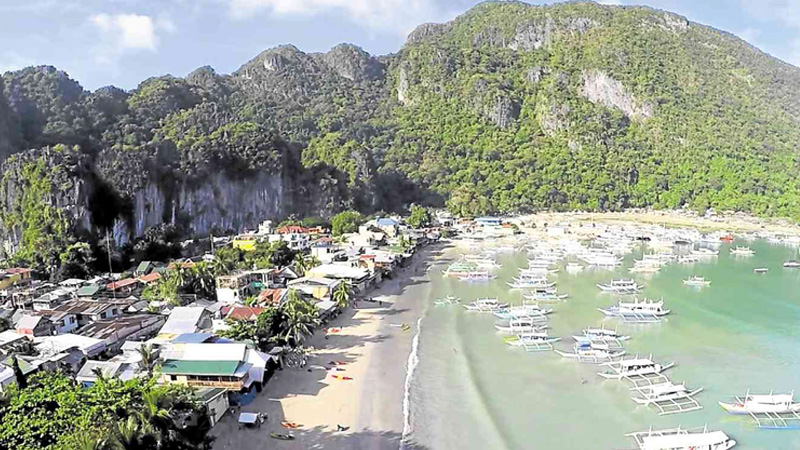

EL NIDO MINUS BIRD NESTS The waves of Bacuit Bay embrace El Nido, a town teeming with tourists but is running low on delectable bird nests built from the saliva of swiftlets and are painstakingly harvested from its karst mountains in northern Palawan province. Collectors lament the decline in their unique trade despite the rise in tourism revenue. REDEMPTO ANDA / INQUIRER SOUTHERN LUZON

EL NIDO, Palawan—Bayron Abos considers himself one of the last of El Nido’s “busyador”—men who climb the resort town’s rugged limestone cliffs to collect bird nests and sell them to mostly Chinese clients.

Faced with a rapidly growing tourism industry, El Nido, a postcard-pretty town in northern Palawan whose name was derived from the nest of the “balinsasayaw” (swiftlet), is slowly discarding a unique practice.

“Most of my fellow busyador have already left the business to become tour guides or boatmen. Some have put up their own businesses to serve the needs of tourists,” Abos told the Inquirer.

He said he was trying to save money to build a boat and cash in on the town’s growing tourism business.

The rare wildlife product that El Nido offers is highly sought as an ingredient in Chinese cuisine.

Bird nests, made from solidified saliva of swiftlets, are believed to contain high levels of natural minerals that cure various ailments and strengthen the body’s immune system.

The edible bird nest is produced by a particular species of swiftlet (Aerodramus fuciphagus) commonly found in Palawan and mainland Asia.

Instead of using twigs to build nests for its young, the male swiftlet manufactures them from its saliva in a monthlong mating ritual inside karst crevices and caves inaccessible to natural predators, except man.

The local bird nest trade is believed to date as far back as the early 1920s. Local accounts said the town, then known as Bacuit, had become popular for the product that in 1954, its civil government asked Congress to rename it to El Nido, which translates into “the nest.”

El Nido and its neighboring town of Taytay are considered the center of the trade. The local governments have no record of the actual volume of bird nests traded here, but a study conducted by the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development (PCSD) estimated that the province produces between 60 and 80 kilograms a year.

The nests are sold for P80,000 to P150,000 per kilogram, depending on their quality.

In the market, nests are graded either “primera” (Class A), “buena” (Class B) or “segunda” (Class C). Poor quality nests, in bits and pieces, are classified as “sinisa” (Class D).

Rapid decline

But traders and officials, as well as a recent scientific study, noted that in the last five years, El Nido’s production of bird nests has been on a rapid decline. The quantity and quality of nests have deteriorated, giving busyador and buyers much lower income.

“The balinsasayaw business is down. I suspect it is also because of climate change and the extreme heat nowadays,” said Pacita Paredes, a buyer and trader.

“Birds actually prefer the warm weather but we’ve been experiencing unusual heat today. The bird population might have declined or they moved elsewhere. I know of cave concessions that no longer produce as much nests as they used to,” Paredes said.

Marvin Acosta, municipal tourism officer, agreed with the observation. “It looks like El Nido’s bird nest is slowly becoming a historical relic. Tourism is eating it up,” he said.

A 2015 PCSD study authored by Glenda Cadigal provided a glimpse into the industry’s predicament: “The impending threat of system collapse is not far in the future if the current harvesting pattern is not addressed. There is a need to prioritize the conservation of the swiftlets and sustainable harvest of their nests.”

No management plan

The local government admits it is unaware of the exact reasons for the decline in the swiftlet population, as there has been no scientific monitoring of its habitat and the possible impact of climate change and tourism activities on bird behavior.

Vice Mayor Leonor Corral said while the town had not been remiss in regulating the trade, more should be done.

“There are regulations concerning the bird nest trade and cave management, but we don’t have a management plan to make it sustainable,” she said.

The local government of El Nido collects fees from cave concessions while the PCSD, a special agency tasked with implementing Republic Act No. 9072 (National Caves and Cave Resources Management and Protection Act), collects fees for trading permits. The PCSD shares this revenue with the local government.

But Corral criticized the PCSD for failing to undertake efforts to properly manage El Nido’s caves.

“With the passage of the [law], the management [of the town’s caves] was taken away from the local government. However, the PCSD just collects fees; they don’t do any management. There should be a management plan. We’re even willing to implement it),” Corral said.

Acosta said some officials had suggested imposing a “closed season” for bird nest gathering, even without the support of any scientific data on what was happening to the caves.

Some traders believe the birds have not completely left El Nido, with many raising the possibility that the primary problem lies on the rampant stealing of nests by nonresidents, Paredes said.

“The birds are still there; I think they have not left. What we are seeing is the increasing cases of theft and cave intrusion and the proliferation of illegal traders,” she said.

A local eatery owned by Paredes, which caters mainly to backpacking tourists, offers the bird’s nest soup for P200 a bowl. Still, the soup has hardly become a mainstream fare among tourists who come to El Nido for its famous beaches and islands.

Unbridled tourism

Early this month, the New York-based Travel and Leisure magazine declared Palawan the “world’s best island,” with the iconic picture of El Nido and its karst mountains accompanying the announcement.

The distinction wasn’t the first. Conde Nast Traveler Magazine last year granted the same title to Palawan.

El Nido never had it so good in tourism income for locals. But local officials have their hands full trying to cope with myriad of management problems arising from the rapid increase of tourists.

Arrivals have picked up steadily over the last five years, from a low of 10,000 visitors in 1994 to last year’s record 160,000. “Nowadays, we receive about 12,000 visitors each month,” Acosta said.

But problems soon became evident for the small seaside community that has caught tourists’ attention.

With the town lacking a proper drainage and sewage system, waste generated by tourism establishments that have sprouted uncontrollably in the last five years started to hurt tourism.

Last year, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) alerted local officials to the rising chloroform levels on the main beach fronting the town proper, a picture-perfect cove that had become the iconic symbol of El Nido.

Business establishments, mostly budget hotels and restaurants, have been built right on the coastline in clear disregard of national zoning policies that provide for easement.

During high tide, sea water reaches the doors of these establishments and submerges whatever is left of the beach. Nobody strolls on the beach of Bacuit Bay during high tide because there simply is no dry sand to walk on anymore.

“It’s the fault of the previous administrations that they allowed construction of these properties way past the easement. Now we have no choice but to undo it,” Corral said.

The local government has engaged establishments in a dialogue to map out a clearing plan that will entail voluntary dismantling of mostly concrete structures after five to seven years.

“It’s a phaseout plan to abide by the 3-meter easement provided in the Water Code (Presidential Decree No. 1067) and an additional 2 meters according to our land use plan. Within three years, we will clear structures made of light materials. In five years, we will do away with the semi-concrete buildings, and in seven years, the permanent structures would be demolished,” Acosta said.

Social injustice

The provincial government has also started to bid out a P245-million sewage and water system project to address one of El Nido’s major problems.

Local officials are also pushing the development of other tourist attractions in El Nido to decongest visitor traffic on the islands in Bacuit Bay, the town’s main destinations.

For one, white sand beaches found on the other side of town have started to become popular destinations for visitors.

With rapid development taking place in otherwise pristine areas, such as Nacpan Beach, some residents also said they were being eased out of access to the beaches by investors working in collusion with some government officials.

“We have a property fronting these beaches and now the DENR wants us to leave because outsiders have come in to take possession of these beaches,” couple Ruperto and Julieta Belinario told the Inquirer.

The Belinarios said the DENR had issued an order evicting them from the foreshore where they built houses, after the agency issued a separate title to a portion of the property owned by their family.

“It’s unfair that they took the property of my grandparents and they want us to leave right away while they continue to allow the illegal occupation by restaurants in Bacuit,” a family member said.

The Belinario couple appealed to President Duterte and Environment Secretary Gina Lopez to help them recover their ancestral property from land grabbers, who they claimed worked in cahoots with DENR personnel and local property dealers whom they did not identify.