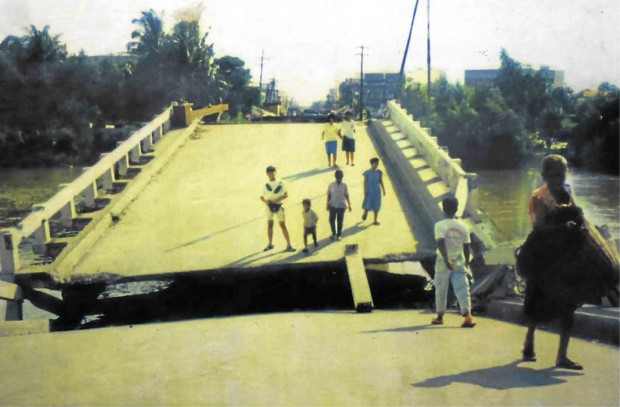

QUINTOS Bridge in Dagupan City was cut in half when the July 16, 1990 quake struck but 26 years later, a new generation of city folk traverse a new Quintos Bridge along Perez Boulevard. WILLIE LOMIBAO/INQUIRER NORTHERN LUZON

DAGUPAN CITY—This coastal city looked like it was bombed out right after a magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck Luzon on July 16, 1990.

It was 4:30 p.m. (daylight saving time) when the ground moved and roared—liquefying the soil, twisting electric poles, sinking or tilting buildings, collapsing a bridge, crushing concrete roads and trapping many vehicles in cracks the size of houses.

People, anguish written all over their faces and mostly unshod, walked or ran like zombies. They were running back home or looking around for their young ones as the quake struck just as classes had been dismissed.

At first glance, the city was a scene of devastation and appeared doomed to extinction.

But when the dust settled, while the city sank by an average of a meter, most buildings were left standing, although 74 sank and 34 tilted. These were mostly in the “liquefied” area—from Perez Boulevard and three blocks going to A.B. Fernandez Street.

Liquefaction is a phenomenon that causes soil to behave like liquid during quakes.

“No buildings in the city actually collapsed or crumbled, although some of those that swayed and tilted suffered damage,” said Nicanor Melecio, chair of Pangasinan Institute for Land and Aquatic Research, and consultant of the city government.

Two concrete buildings of the University of Luzon (UL, then Luzon Colleges) at the heart of the high-damage zone were left standing and did not tilt. The UL campus, however, sank by half a meter, said Nelson Rosario, the university’s building superintendent.

Only wooden structures near Perez Boulevard collapsed. Many buildings survived because they had “combined footing foundation” which is two or more columns on a straight line that carry the weight of floors, said Aurora Samson-Reyna, UL vice president for academic affairs.

Reyna said the concrete buildings stood on a marshland, which could be the reason the architect-engineer who designed them used the combined footing foundation.

Two other universities also did not lose buildings to the earthquake—University of Pangasinan and Lyceum Northwestern University. Both, however, were outside of the liquefaction area.

Along A.B. Fernandez Street, two hotels stood their ground. One is Vicar Hotel which was built in 1950 when the city was recovering from World War II.

Vicar survived without any damage, said Rebecca Lapore, 65, who recalled being in her small store beside the hotel when the quake struck.

“It was pandemonium,” Lapore said, recalling scenes during the quake.

Another landmark that survived is Hotel Victoria, which was much younger than Vicar, with two buildings (one built in 1970 and the other in 1975).

Melecio said the 1990 quake tested the strength of the buildings which are likely to survive another quake with the same force.

The 1990 quake produced a 125 kilometer-long rupture that stretched from Dingalan, Aurora province, to Kapaya, Nueva Vizcaya province, that was attributed to movements of the Philippine Fault Zone and Digdig Fault, according to the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology.