(Last of two parts)

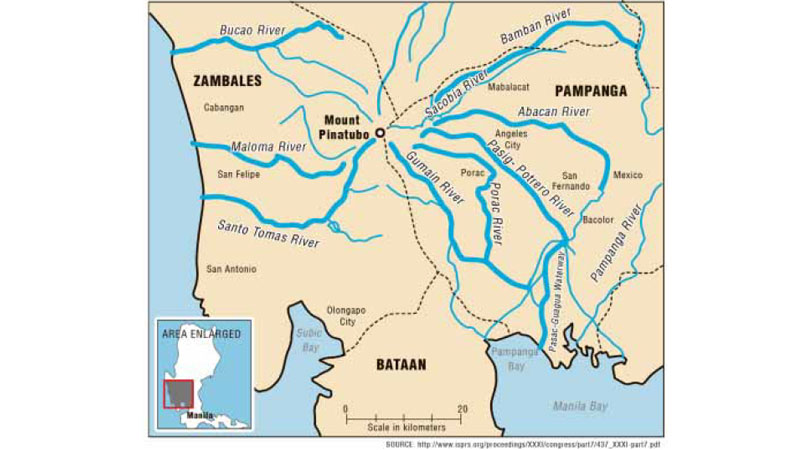

CITY OF SAN FERNANDO—Not only were lives and properties lost to the 1991 Mt. Pinatubo eruption and succeeding lahar flow (volcanic debris washed down by rains from the slopes). Rivers were also among those erased by nature’s destructive forces.

And while people have already rebuilt from the disaster, rivers are taking more time to come back to life.

The Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) has opened the original channel of Pasig-Potrero River and built a transverse dike to drain the water out and direct it toward Manila Bay via Pasac River through the towns of Minalin and Sasmuan in Pampanga province.

With high river beds and a small volume of water during dry months, the eight major rivers linked to Mt. Pinatubo are not navigable by boats.

Portions of Pasac River in Sasmuan dry up, making Orani town in neighboring Bataan province just a walking distance.

In rainy months, however, Pasac River does not drain out efficiently, causing water to flow back inland. This takes place because tide levels are higher at the mouth of Manila Bay.

The discrepancy reaches a meter or two, according to a study done in 2002 by the Japanese consulting firm Nippon Koie for the Mt. Pinatubo Hazard Urgent Mitigation Project Phases 3 and 4 that would cover Pasac delta, Porac-Gumain River and a new third river carved out from Mexico, San Fernando and Minalin towns.

According to the study, lands also sink in the Pasac area at around 20 millimeters per year and long-term sea level changes are assumed at 5 mm yearly.

Silt and trash

The 260-kilometer-long Pampanga River, which drains more than 30 rivers in Central Luzon, also leads to Manila Bay, bringing silt and trash.

“Sediment yields on Porac-Gumain and Pasig-Potrero rivers are still several times higher than under pre-eruption conditions, and are expected to remain high for the next few decades,” the study said.

With high sand loads, it said, “it will be extremely difficult to permanently restore channels to conditions that existed prior to the eruption.”

“All rivers in the project area have been subject to significant modification by both natural processes (lahar and sediment movements resulting from the Mt. Pinatubo eruption) and man-made interventions,” the study said.

These include building channels to divert water flow, dredging river beds, building levees and embankments for fish farming.

“These factors have contributed to significant changes in the habitat value and overall biological productivity of the riverine ecosystem,” it said.

Mangroves and nipa trees, estimated to have occupied 20 to 30 percent of the area at the mouth of Pasac River in 1977, have been destroyed by the eruption or cleared for fishponds.

As rivers were choked with lahar, the area used for freshwater fishponds have been reduced from 9,105 hectares in 1989 to 8,140 ha to the present, according to the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources.

Brackish water areas in Pampanga near Manila Bay have expanded about six times to 29,084 ha from 5,342 ha in 1989.

Gray highway

In Tarlac province, O’Donnell River looks like a gray highway on dry months and a pathway of lahar that rains scour from tall canyons.

Sacobia and Bamban rivers are choked with lahar. Sections near MacArthur Highway are 1-2 meters below the spilling levels of dikes.

In Zambales province, the riverbed in the midstream and downstream of Bucao, Maloma and Sto. Tomas rivers have “remarkably” risen, according to the Nippon Koie study.

By 2015, several sections of those rivers were higher than the levels of dikes, indicating slow water discharge toward the sea.

The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) estimated the amount of volcanic debris at 2.8 billion cubic meters in Bucao, 0.6 billion cubic meters in Sto. Tomas, and 0.1 billion cubic meters in Maloma.

“As a result of the massive lahar deposit accumulated along the concerned riverbeds, most of the aquatic flora and fauna have been destroyed since the eruption of Mt. Pinatubo. The priority structural measures should be able to stabilize the river water flow and contribute to recovery of the aquatic flora and fauna,” the study said.

Never forget

Pampanga Gov. Lilia Pineda urged the people not to forget the Pinatubo disaster because it “developed courage, unity and resiliency in our people and deepened our faith in God.”

“Our challenge now is let the next generations know this kind of natural hazard and what we Kapampangans did to overcome it,” she said.

Pineda thanked former Presidents Fidel Ramos, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and Benigno Aquino III for helping Pampanga and the rest of Central Luzon through infrastructure, livelihood and housing projects that fast-tracked the rehabilitation process.

“We must thank also the business sector because despite the odds and risks, they did not leave Pampanga and instead invest more in it,” the governor said.

Businessman Levy Laus, former president of the Save San Fernando Movement, said Pampanga survived because national leaders heeded appeals to save the province from plans to let nature take its course and to relocate the people to Mindanao or Palawan.

The economy of Central Luzon showed signs of fast recovery in the last 24 years, according to Greg Pineda, assistant regional director of the National Economic and Development Authority.

He cited the gross regional domestic product that reached 7.61 percent in 1988 slumped to a negative 2.4 percent in 1991, but recovered at 9 percent in 2014.

“The pre-eruption level was not restored until 2009. Incidentally, in 1998 growth rate registered -6.77 percent attributed to the Asian financial crisis of 1997,” he said.

The mushrooming of shopping malls and car retail in the region’s key cities since 2000 was another indication that the economy had weathered the disaster, he said.