Showing the human side of heroes

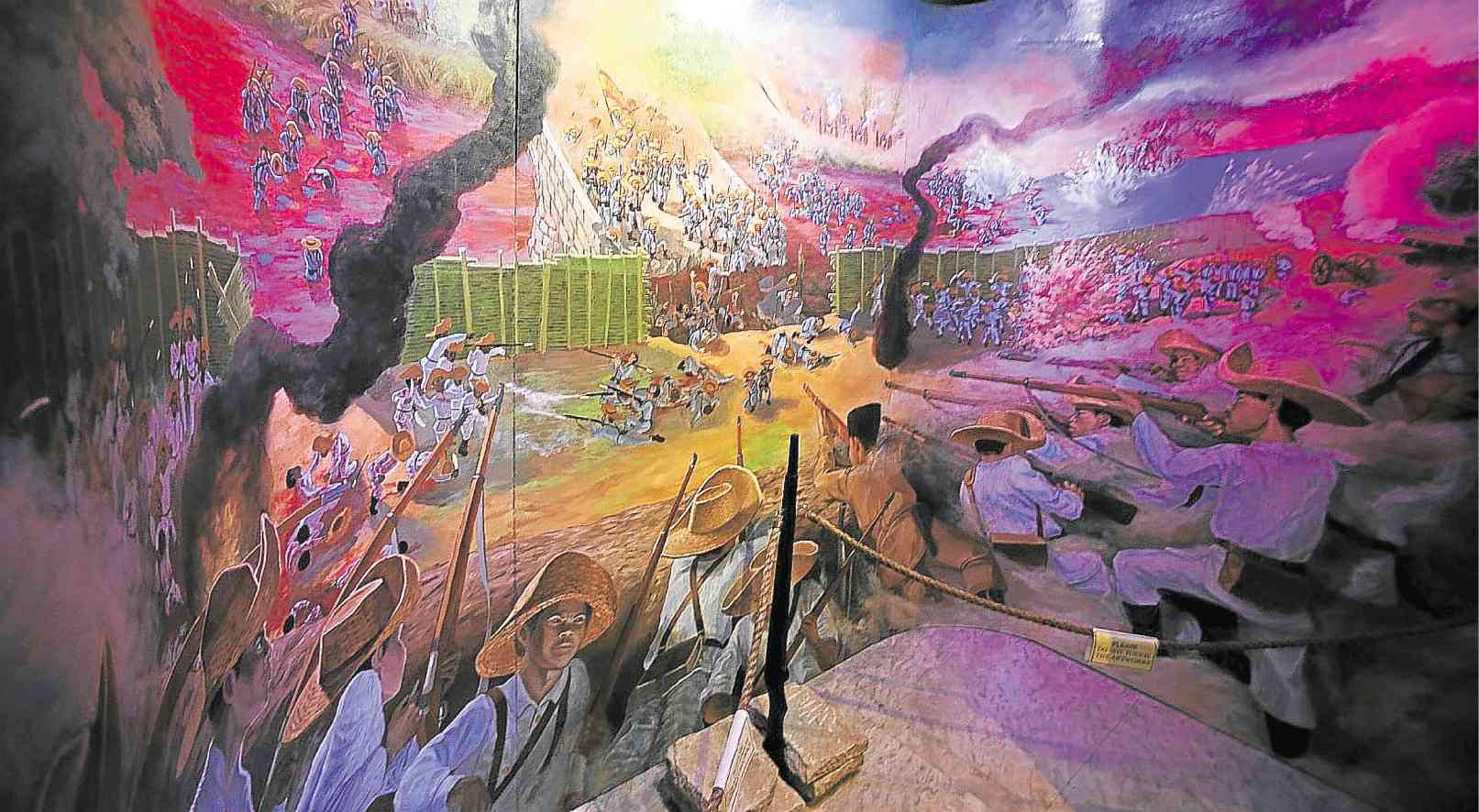

BATTLE The General Emilio Aguinaldo Museum in Baguio City features a mural of the Battle of Zapote Bridge where 10,000 revolutionary soldiers defeated 20,000 Spanish troops on Feb. 17, 1897. EV Espiritu

AT THE FOOT of Mt. Arayat, the rustic town of Arayat had always known that the late Gen. Jose Alejandrino, once a military governor of Pampanga province, was a hero in the revolution against Spain in 1896 and against the United States in 1898.

There is adequate respect here for the man long after his death in 1951. Arayat claimed Alejandrino as its son though he was born in Binondo, Manila, of parents from Arayat.

When a fire struck the old town hall in the 1970s, residents moved his post-World War II monument from the glorietta to the plaza of the current town hall. There is a day dedicated to Alejandrino, held every Dec. 1, his birth date.

But Alejandrino gave more to the nation.

He wrote “La Senda del Sacrificio,” which was published in Spanish in 1933 when he was 63, filling it with details based on his being a participant in the struggle for independence.

Article continues after this advertisementAlejandrino allowed a relative, lawyer Jose M. Alejandrino, to translate the book into English in 1949, titling it “The Price of Freedom” with the subtitle “Episodes and anecdotes of our struggles for freedom.”

Article continues after this advertisementIn both languages, the book is a “primary source [of information] for historians,” historian Ambeth Ocampo said.

Worth reading

“Eight decades since it was first published, [Alejandrino’s book] is still worth reading because we not only get a glimpse at the human side of our heroes but the challenges that the young nation faced a century ago have resonance and relevance to us in the 21st century,” Ocampo said in an interview by e-mail.

Those who want to know more about

Dr. Jose Rizal and Gen. Antonio Luna can read Alejandrino “with much profit,” he said.

Aside from leading the team that bought firearms for the 1896 revolution, Alejandrino worked with Rizal and Luna in the propaganda movement in Europe. He was also Luna’s chief of engineers.

He dedicated his book to his father, Mariano, who was exiled by Spanish friar Juan Tarrero to Kiangan town (in Ifugao province) on an allegation that he was a Freemason. His brothers—Joaquin, Manuel, Anselmo and Pastor—also fought in the revolution.

The general, according to the translator, was hesitant to have his memoirs published, wary of offending people with the truth. In the 1933 prologue, the late Teodoro Kalaw, director of the National Library, admitted that he had “great difficulty” convincing Alejandrino to agree to publish.

National soul

Alejandrino opened the first of 10 chapters by tackling the “national soul … created by legends, traditions and history of every people … enriched by deeds which are glorious and of great benefit to humanity.”

Of Rizal, he said, “It appears strange to me that some of his biographers have presented Rizal as completely opposed to the revolution of 1896 when what really happened was this: The Katipunan, on the eve of the rebellion, wanted to know the opinion of Rizal and they sent to Dapitan one of their members, Pio Valenzuela, under a plausible pretext.”

“Upon being informed in detail of the organization and resources of the Katipunan, he (Rizal) opined that the revolt should be delayed and proposed the cooperation of the educated and rich elements be assured first, pointing to Antonio Luna as one possible liaison between the popular mass and the educated and rich class, Moises Salvador and Mamerto Natividad, who initiated me in the Katipunan, knowing the friendship which I had with Luna, requested me to transmit to him the recommendation of Rizal but Luna refused on that occasion to join the revolutionary movement because he believed it was still premature,” Alejandrino wrote.

He next presented the men he closely worked with, providing details of their characters, most cast in endearing qualities.

In defense of Gen. Emilio Aguinaldo (Magdalo head and later, President of the First Republic), Alejandrino devoted a whole chapter on Andres Bonifacio, Katipunan supremo and Magdiwang head, centering on his tragic death.

He questioned the authenticity of the minutes of a March 23, 1897, meeting where Bonifacio protested the alleged frauds by Aguinaldo. He cited minutes of another secret meeting in Naic, Cavite province, of Bonifacio and his supporters who stated the same allegations.

Alejandrino pointed out that the “grave charges of treason and connivance with the enemy contained in the preamble of these minutes against the principal chiefs of the Magdalo have not been substantiated or confirmed by a subsequent act or event, and consequently, are gratuitous and highly unjust.”

“If there really existed antagonism and rivalry between Magdiwang and Magdalo, this protest and the secret meeting held at Naic became instrumental in further aggravating the situation and in widening the differences to such an extent that it became imperative that one of the two chiefs must be eliminated for the furtherance of the cause and for the sake of unity,” he said.

Period of struggle

In the next chapter, Alejandrino called the pact agreed in Biak na Bato in Bulacan province in December 1897 to have ended the “first period of struggle.”

He gave details as to how Aguinaldo handled the P400,000 indemnity by Spain, adding, “detailed receipts and vouchers regarding the disposal of the funds received by Galicano Apacible are in his possession.”

In the longest chapter, Alejandrino presented Luna in many situations. They were friends since 1889 in Spain, reuniting in July 1898 after Luna served jail terms there.

He put Luna in context, explaining, “In order to appreciate duly the work of Luna and to justify the energetic and violent measures which he adopted during the campaign, it is necessary to recall the men who figured at the head of the government and the state of conditions in which the Philippine Army was found in that critical moment.”

Alejandrino revealed defects in the government, saying the Cabinet consisted of men who had “no initiative, being subservient to the will of the President.” The artillery and cavalry were in “rudimentary stage” while the Army’s regional organizations “impaired greatly their unity and solidarity because most of the generals recognized only Aguinaldo.”

Alejandrino gave possible reasons Luna was killed:

“There exist no doubt whatsoever that the tragic end of Luna was premeditated, and if anything can justify this ignominious act, it is that the members of the Cabinet—educated men, cultured and intelligent, headed by [Pedro] Paterno and [Felipe] Buencamino and generals very loyal to Aguinaldo—considered and made Aguinaldo believe that Luna was a pernicious man who was a hindrance to unity in our government.”

The general called the death of Luna as the “greatest stain that Aguinaldo had consented to be written in the annals of our history. It is the greatest disgrace which he has caused by his weakness to fall over his name and his life history.”