Finns to bury nuclear waste in world’s costliest tomb

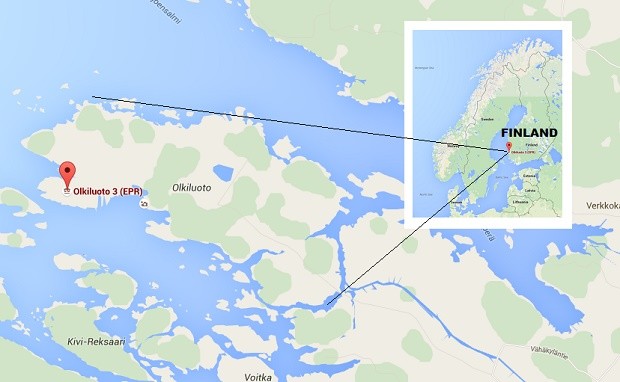

This tiny island on the western part of Finland will be the final resting place of nuclear waste from the country’s nuclear power plants. GOOGLE MAP

EURAJOKI, Finland — Deep underground on a lush green island, Finland is preparing to bury its highly-radioactive nuclear waste for 100,000 years — sealing it up and maybe even throwing away the key.

Tiny Olkiluoto, off Finland’s west coast, will become home to the world’s costliest and longest-lasting burial ground, a network of tunnels called Onkalo — Finnish for “The Hollow”.

Countries have been wrestling with what to do with nuclear power’s dangerous by-products since the first plants were built in the 1950s.

Most nations keep the waste above ground in temporary storage facilities but Onkalo is the first attempt to bury it for good.

Starting in 2020, Finland plans to stow around 5,500 tons of nuclear waste in the tunnels, more than 420 meters (1,380 feet) below the Earth’s surface.

Already home to one of Finland’s two nuclear power plants, Olkiluoto is now the site of a tunneling project set to cost up to 3.5 billion euros ($4 billion) until the 2120s, when the vaults will be sealed for good.

“This has required all sorts of new know-how,” said Ismo Aaltonen, chief geologist at nuclear waste manager Posiva, which got the green light to develop the site last year.

The project began in 2004 with the establishment of a research facility to study the suitability of the bedrock.

At the end of last year, the government issued a construction license for the encapsulation plant, effectively giving its final approval for the burial project to go ahead.

At present, Onkalo consists of a twisting five-kilometer (three-mile) tunnel with three shafts for staff and ventilation. Eventually the nuclear warren will stretch 42 kilometers (26 miles).

The temperature is cool and the bedrock is extremely dry — crucial if the spent nuclear rods are to be protected from the corrosive effects of water.

Safety questions

The waste is expected to have lost most of its radioactivity after a few hundred years, but engineers are planning for 100,000, just to be on the safe side.

Spent nuclear rods will be placed in iron casts, then sealed into thick copper canisters and lowered into the tunnels.

Each capsule will be surrounded with a buffer made of bentonite, a type of clay that will protect them from any shuddering in the surrounding rock and help stop water from seeping in.

Clay blocks and more bentonite will fill the tunnels before they are sealed up.

The method was developed in Sweden where a similar project is under way, and Posiva insists it is safe.

But opponents of nuclear power, such as Greenpeace, have raised concern about potential radioactive leaks.

“Nuclear waste has already been created and therefore something has to be done about it,” said the environmental group’s Finnish spokesman Juha Aromaa. “But certain unsolved risk factors need to be investigated further.”

In 100,000 years’ time

Planning the nuclear graveyard involves asking the impossible — how can we know what this little island will be like in 100,000 years? And who will be living there?

To put the timeframe into perspective: 100,000 years ago Finland was partly covered by ice, Neanderthals were roaming Europe and Homo Sapiens were starting to move from Africa to the Middle East.

Geologists cannot rule out another ice age. Finland is not particularly prone to seismic activity, but engineers must ensure Onkalo can withstand any tectonic motion caused by another deep chill in the millennia to come.

A 2015 study by the University of Turku warned that in the event of a new ice age, the permafrost could reach some 200 meters deeper than where the rods would be buried.

Posiva’s own research in western Greenland says that when land is repeatedly covered by glaciers or ice sheets, the rock does fracture — but not as far down as the waste.

Nevertheless, Finnish nuclear safety authority STUK has demanded more modelling from the company on the possible long-term effects of a freeze.

Along with the land itself, there is the question of the people living on it, and Aaltonen admits it’s impossible to predict what kind of civilization might be settled there 100,000 years from now.

An unmarked grave?

In terms of protecting the site, the main issue is ensuring the tunnels are backfilled then sealed with huge ferro-concrete plugs, making them completely inaccessible to curious onlookers or anyone seeking to make off with the waste.

For this reason, Posiva is mulling whether to landscape the site as if there was nothing there.

“It is still being discussed if the place should be marked with warning signs,” he said.

But history shows that such warnings often have the opposite effect, such as in ancient Egypt where measures put in place to protect the Pharaohs’ tombs inside the Pyramids were ignored.

“There are examples like in Egypt, where a curse was to fall upon the person who passed a certain door and of course, people just entered there,” he said.

For now, Olkiluoto’s current residents have grown used to living nextdoor to two nuclear reactors, with a third under construction.

Local vegetable farmer Timo Rauvola was sanguine about the plans for a nuclear burial ground.

“Personally, I believe that when (the waste) is placed deep down there with care and expertise, it is better than how it is now around the world — placed wherever.”