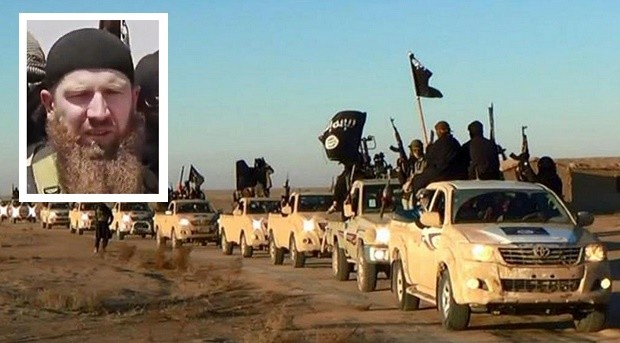

In this undated file photo ISIS militants hold up their weapons and wave its flags on their vehicles in a convoy on a road leading to Iraq, while riding in Raqqa city in Syria. The U.S. -led coalition has been targeting top ISIS officials. Over the past months, American officials have said that the U.S. has killed a string of top commanders from the group, including its “minister of war” Omar al-Shishani (inset), feared Iraqi militant Shaker Wuhayeb, also known as Abu Wahib. AP FILE

BAGHDAD, Iraq — In March, a senior commander with the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) group was driving through northern Syria on orders to lead militants in the fighting there when a drone blasted his vehicle to oblivion.

The killing of Abu Hayjaa al-Tunsi, a Tunisian jihadi, sparked a panicked hunt within the group’s ranks for spies who could have tipped off the U.S-led coalition about his closely guarded movements. By the time it was over, the group would kill 38 of its own members on suspicion of acting as informants.

READ: ISIS executes 8 Dutch jihadists for wanting to leave — activists | ISIS ‘may set up caliphate in Southeast Asia’

They were among dozens of ISIS members killed by their own leadership in recent months in a vicious purge after a string of airstrikes killed prominent figures. Others have disappeared into prisons and still more have fled, fearing they could be next as the jihadi group turns on itself in the hunt for moles, according to Syrian opposition activists, Kurdish militia commanders, several Iraqi intelligence officials and an informant for the Iraqi government who worked within ISIS ranks.

The fear of informants has fueled paranoia among the militants’ ranks. A mobile phone or internet connection can raise suspicions. As a warning to others, ISIS has displayed the bodies of some suspected spies in public — or used particularly gruesome methods, including reportedly dropping some into a vat of acid.

ISIS “commanders don’t dare come from Iraq to Syria because they are being liquidated” by airstrikes, said Bebars al-Talawy, an opposition activist in Syria who monitors the jihadi group.

Over the past months, American officials have said that the U.S. has killed a string of top commanders from the group, including its “minister of war” Omar al-Shishani, feared Iraqi militant Shaker Wuhayeb, also known as Abu Wahib, as well as a top finance official known by several names, including Haji Iman, Abu Alaa al-Afari or Abu Ali Al-Anbari.

In the northern Iraqi city of Mosul, the biggest city held by ISIS across its “caliphate” stretching across Syria and Iraq, a succession of militants who held the post of “wali,” or governor, in the province have died in airstrikes. As a result, those appointed to governor posts have asked not to be identified and they limit their movements, the Iraqi informant told The Associated Press. Iraqi intelligence officials allowed the AP to speak by phone with the informant, who spoke on condition of anonymity, fearing for his life.

The purge comes at a time when ISIS has lost ground in both Syria and Iraq. An Iraqi government offensive recaptured the western city of Ramadi from ISIS earlier this year, and another mission is underway to retake the nearby city of Fallujah.

Rami Abdurrahman, who heads the Britain-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, said some ISIS fighters began feeding information to the coalition about targets and movements of the group’s officials because they needed money after the extremist group sharply reduced salaries in the wake of coalition and Russian airstrikes on ISIS-held oil facilities earlier this year. The damage and the loss of important ISIS-held supply routes into Turkey have reportedly hurt the group’s financing.

“They have executed dozens of fighters on charges of giving information to the coalition or putting (GPS) chips in order for the aircraft to strike at a specific area,” said Abdurrahman, referring to ISIS in Syria.

The militants have responded with methods of their own for rooting out spies, said the informant. For example, they have fed false information to a suspect member about the movements of ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, and if an airstrike follows on the alleged location, they know the suspect is a spy, he said. They stop fighters in the street and inspect their mobile phones, sometimes making the fighter call any unusual numbers in front of them to see who they are.

After the killing of al-Anbari, seven or eight ISIS officials in Mosul were taken into custody and have since disappeared, their fates unknown, said the informant.

“Daesh is now concentrating on how to find informers because they have lost commanders that are hard to replace,” said a senior Iraqi intelligence official in Baghdad, using the Arabic acronym for the Islamic State group. “Now any ISIS commander has the right to kill a person whom they suspect is an informer for the coalition.”

Another Iraqi intelligence official said at least 10 ISIS fighters and security officials in Mosul were killed by the group in April on suspicion of giving information to the coalition because of various strikes in the city.

Mosul also saw one of the most brutal killings of suspected informants last month, when about a dozen fighters and civilians were drowned in a vat filled with acid, one senior Iraqi intelligence official said.

In the western province of Anbar, the Iraqi militant Wuhayeb was killed in a May 6 airstrike in the town of Rutba. Wuhayeb was a militant veteran, serving first in al-Qaida in Iraq before it became the Islamic State group. He first came to prominence in 2013, when a video showed him and his fighters stopping a group of Syrian truck drivers crossing Anbar. Wuhayeb asks each if he is Sunni or Shiite, and when they say Sunni, he quizzes them on how many times one bows during prayer. When they get it wrong, three of them admit to being Alawites, a Shiite offshoot sect, and Wuhayeb and his men lay the three drivers in the dirt and shoot them to death.

After Wuhayeb’s killing, ISIS killed several dozen of its own members in Anbar, including some mid-level officials, on suspicion of informing on his location, and other members fled to Turkey, the two intelligence officials said. They spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to talk to the press.

Some of the suspects were shot dead in front of other ISIS fighters as a lesson, the Iraqi officials said.

After the Tunisian militant Abu Hayjaa was killed on the road outside Raqqa on March 30, ISIS leadership in Iraq sent Iraqi and Chechen security officials to investigate, according to Abdurrahman and al-Talawy, the Syria-based activist. Suspects were rounded up, taken to military bases around Raqqa, and the purge ensued. Within days, 21 ISIS fighters were killed, including a senior commander from North Africa, Abdurrahman said.

Dozens more were taken back to Iraq for further questioning. Of those, 17 were killed and 32 were expelled from the group but allowed to live, Abdurrahman and al-Talawy said, both citing their contacts in the militant group. Among those brought to Iraq was the group’s top security official for its Badiya “province,” covering a part of central and eastern Syria. His fate remains unknown.

Non-ISIS members are also often caught up in the hunt for spies. In the Tabqa, near Raqqa, ISIS fighters brought a civilian, Abdul-Hadi Issa, into the main square before dozens of onlookers and announced he was accused of spying. A masked militant then stabbed him in the heart and, with the knife still stuck in the man’s chest, the fighter shot him in the head with a pistol.

Issa’s body was hanged in the square with a large piece of paper on his chest proclaiming the crime and the punishment. ISIS circulated photos of the killing on social media.

According to al-Talawy, several other ISIS members were killed in the town of Sukhna near the central Syrian city of Palmyra on charges of giving information to the coalition about ISIS bases in the area as well as trying to locate places where al-Baghdadi might be.

Sherfan Darwish, of the U.S.-backed Syria Democratic Forces, which has been spearheading the fight against ISIS in Syria, said there is panic in ISIS-held areas where the extremists have killed people simply for having telecommunications devices in their homes.

“There is chaos. Some members and commanders are trying to flee,” Darwish said.

The U.S. -led coalition has sought to use its successes in targeting ISIS leaders to intimidate others. In late May, warplanes dropped leaflets over ISIS-held parts of Syria with the pictures of two senior militants killed previously in airstrikes. “What do these Daesh commanders have in common?” the leaflet read. “They were killed at the hands of the coalition.”

The jihadis have responded with their own propaganda.

“America, do you think that victory comes by killing a commander or more?” ISIS spokesman Abu Mohammed al-Adnani said in a May 21 audio message. “We will not be deterred by your campaigns and you will not be victorious.”