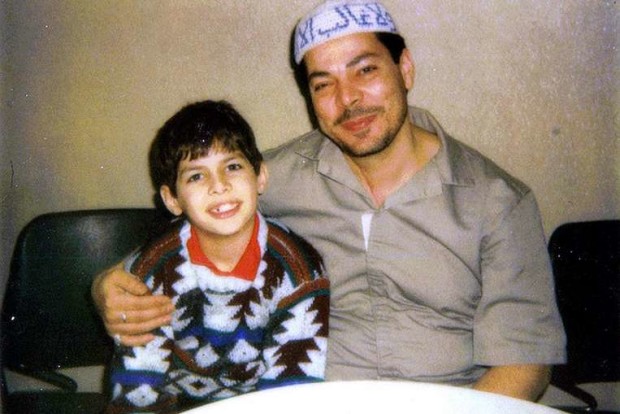

A young Mr Zak with his father, El Sayyid Nosair, who was convicted of helping to plan, from his prison cell, the 1993 bombing of World Trade Center in New York. PHOTO: COURTESY OF ZAK IBRAHIM

On Nov 5, 1990, Zak Ibrahim’s life changed inexorably.

His mother was at home in New Jersey watching television when news broke that Rabbi Meir Kahane – a right-wing politician and the founder of the Jewish Defense League – had been shot.

The assailant was Zak’s father, El Sayyid Nosair.

“There was footage of him lying in a pool of blood and being put into an ambulance,” says Zak, who was just seven years old at that time. “It was my mother’s introduction to his radical ideology.”

If the family clung to any belief he was innocent, it vanished when El Sayyid was convicted of helping to plan, from his prison cell, the 1993 bombing of World Trade Center (WTC) in New York, which left six people dead and more than 1,000 injured.

Being the son of the first Islamic extremist to commit murder in the United States was an albatross Zak, now 33, carried around his neck for a long time.

He changed his name and moved at least 30 times, paralyzed by the fear that people would think his father’s blood ran in his veins. His peripatetic existence made him an easy target for bullying which, ironically, drove him to make a stand against bigotry and hatred and everything his father represented.

About nine years ago, he started sharing his story publicly. He even wrote a book, The Terrorist’s Son: A Story Of Choice, which was published by Ted Books in 2014.

Violence, he asserts, has no place in this world. “I believe there is value in having people understand that I was exposed to this violent ideology but I chose to promote peace. And if I could do that, what about the large majority of Muslims who are not exposed to this level of extremism?” says Zak, who was in Singapore recently to speak at the Credit Suisse Global Me- gatrends Conference at Swissotel.

Stocky and robustly hirsute, the peace activist has a velvety voice, made even more pleasant by his calm and measured tone.

His mother was Karen Mills, a white American who grew up as a Catholic.

“She met my father on the night she converted to Islam. My father was born and raised in Port Said in Egypt and came to the US in 1981 for better opportunities,” he says.

The couple got married a few weeks after meeting. “I came along a year later. I have a younger brother as well as a stepsister from my mother’s previous marriage.”

Life was normal for the first few years. But when Zak was five, the family had to move from Pennsylvania to New Jersey after his father was accused of sexual assault by a woman who had a history of mental illness.

“No charges were filed. In fact, the judge dismissed the case because there was no evidence that it took place. But the accusation ruined his reputation in the community.”

Things worsened when his electrician father fell off a ladder while at work and suffered third-degree burns on his arms. “He became withdrawn and depressed and spent a lot of time in a corner of the living room by the heater reading the Quran,” he recalls.

Not long after, El Sayyid started consorting with Mohammad Salameh, Ramzi Yousef and the other men responsible for the 1993 WTC bombing.

Even though he was just six, Zak would be dragged along to the mosque to listen to sermons by radicals. His father would even take him to shooting ranges and let him have a go at the gun.

“You assume they have your best interests at heart so I never asked why I was shooting even though it was a strange experience for a kid.”

El Sayyid was acquitted of murdering Kahane but convicted of assault and possession of an illegal firearm. It was not until the WTC bombing that the authorities found out El Sayyid was part of a terrorist network and sentenced him to life imprisonment. It emerged years later that Osama bin Laden had funded his defence trial.

“That was when my mum realized he was not as innocent as he claimed. She filed for a divorce. I was 11 the last time I saw my father face to face,” says Zak, whose father is still behind bars.

Over the next 10 years, the family moved multiple times.

Mr Zak changed his name and moved at least 30 times, paralysed by the fear that people would think his father’s blood ran in his veins. His book, The Terrorist’s Son: A Story Of Choice, is on the reading list of many colleges in the US. PHOTO: MATTHIAS HO FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

“We lived in bad neighborhoods and went to bad schools. I was bullied very badly. I got picked on because I was always the new kid in school, chubby, quiet and have a strange-sounding name. They don’t need reasons. It did great damage to my self-esteem and self-worth.”

It did not help when his mother remarried, and his stepfather was an extremely violent man. “He kept us up at night and made me do push- ups while he hit us with a belt. I was only 15 and he was beating me up like a grown man. Thankfully, they were married for only four years.”

A job at the Busch Gardens theme park in Tampa, Florida, proved to be a big turning point in his life.

Then 18 years old, he came into contact with tourists and colleagues of every creed, color and persuasion. They gave him lessons in love and acceptance.

“I started building relationships with people and started to feel normal. You can’t judge people based on the color of their skin, their religion, their sexuality; it has nothing to do with the quality of a person’s character.”

There was another role model: Jon Stewart, then the host of The Daily Show, a program which blends humor with ascerbic analysis of politics and news events.

“Every male role model I had had been a horrible person but Jon Stewart was talking about things I was interested in. He helped me to break down the arguments against hatred and bigotry and guided me through a lot of the ideas I had in my head. He was a great source of inspiration.”

Zak dropped out after a year in community college in Pittsburgh and started working as a welder in a construction company.

“I wasn’t responsible enough for college. I was listless and had no idea what to do with my life but I knew I did not want to spend 30 years in an office. I wanted to push the world in another direction but I was not sure how,” he says.

By then, he had started confiding his past to some of his close friends.

“Some laughed, some were shocked, some felt bad for me.”

But one friend, whom he told while they were drinking one night, actually pulled a knife on him.

“He told me that if he killed me, he would be doing the US a service. I cut my hand while trying to wrest it from him. He was so drunk that he put the knife on the table, went to the bathroom and when he came back, had forgotten what had happened. The next day, he couldn’t remember a thing,” he recalls with a chuckle.

Not long after, he met artist and spa manager Sharon Mattson at a poker tournament. They started dating. She encouraged him to share his story. “She was the one who had the confidence in me and my story. She put in a lot of work to convince people it was worth getting me to speak on stage and share my story.”

The first gig they secured was the Student Peace Alliance, a student organization advocating peace across the US. “One of the board members came to visit us and actually spent the night with us to make sure I wasn’t some crazy person.”

He ended up being a keynote speaker, in front of 1,500 people, at a convention in Southwestern University in Texas. “I just went up there, half read and half spoke it. At the end of it all, people were on their feet and clapping.”

The speech made headlines and even prompted an e-mail from his father’s lawyer saying that El Sayyid would like to meet him. The meeting did not take place although father and son corresponded for a while.

“Ultimately it was not a healthy conversation. I naively thought I would ask him these questions I had been thinking about for a very long time and that he would answer them honestly and openly. It didn’t go that way at all.”

By then, Zak had become an atheist. “I didn’t leave the religion because of what my father had done. It was just simply my own loss of faith. The idea that a god would create us the way we are and then judge us for eternity for being what we are had all the weaknesses of a human idea to me.”

He and Mattson – they were once engaged but are now good friends and business partners – continued plugging the speaking circuit. “We drove all over the US; we went to Quaker meeting houses, churches, synagogues – anywhere where people would let me share my story. I did it for gas money and cookies; I even did it for free. For the first four or five years, we did not make money, we even lost money.”

Things changed dramatically when he sent in a one-minute video to TED and was invited, along with more than 20 others, to take part in its talent search in New York City in 2013. He was rated the top speaker that night and invited to speak at the main TED conference in Vancouver the following year.

The offer for writing his book came the day after his speech. “They wanted it to be the first TED book in print,” he says, adding that TED had published only online books before that.

Not only did The Terrorist’s Son win the American Library Association Alex Award – given to the 10 best adult books of the year that also appeal to young adult readers – last year, it also made the reading list of many colleges in the US.

The accolades gave his speaking career the fillip it needed; he quit his job, set up a company with Mattson and started speaking full- time. “Before TED, I’d never given a talk outside of the US. Now 50 percent of my talks are delivered outside the US,” says Zak, who has spoken all over Europe and Asia.

He shared the stage and talked about faith with Bishop Desmond Tutu in Oxford University, and even gave a talk on the private island of Virgin head honcho Richard Branson in the Virgin Islands.

Except for a couple of e-mail denigrating what he does, he has never received any death threats.

His family supports what he does and he is now in the process of starting a non-profit with others who, like him, have grown up with hateful ideology and violence. “We want a foundation where people who have those experiences can share them with those susceptible to following in the path of hate and violence,” says Zak. He hopes to keep spreading the message of peace and non-violence.

“Every day, I get to work with people who don’t necessarily have a story like mine and who didn’t grow up with a father like I did but who nevertheless are out there trying to make the world a better place. It’s so motivating.”

RELATED STORIES

Apec leaders unite vs terrorism

Biodiesel ‘fueling’ Boko Haram terrorism