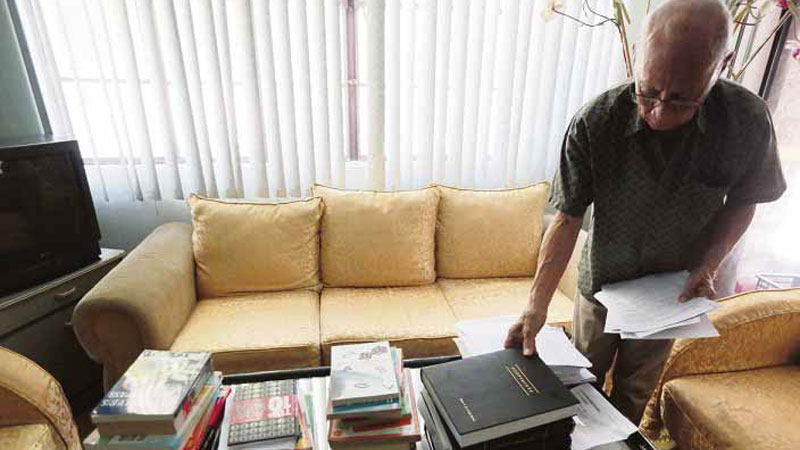

END TOCALVARY Oscar Santos, one of the leaders of Kilus Magniniyog legal team, is hoping a coconut farmers’ trust fund will soon be passed in Congress that will pave the way for the utilization of P71 billion worth of San Miguel Corp. shares recently recovered to rehabilitate the ailing coconut industry and ease crushing poverty among 3.5million coconut farmers. GRIG MONTEGRANDE

(First of two parts)

AS A TEENAGER, Oscar F. Santos learned early on that the income from the family’s small coconut farm on Alabat island in Quezon province wasn’t enough to support his studies or his five siblings.

At the age of 13, he lost his father, who was tortured and killed before his eyes by the Japanese during World War II.

He had to help the family, fishing and farming on the island in Lamon Bay that sweeps out to the Pacific.

Upon liberation, he studied law in Manila while working as a janitor and newsboy, delivering 200 copies of Star Reporter in an area from Legarda to Quiapo in what is now called the University Belt.

He overcame the odds stacked against children, like him, of impoverished coconut farmers, whose families comprise a quarter of the nation’s population, and are courted in this election season. Politicians are promising to end the farmers’ decades-long struggle to recover billions of pesos in assets acquired from a martial law coconut levy scheme—described as the biggest legalized racket in the nation’s history—that are either tied up in a complex web of legal cases or in proposed legislation for their use.

A strapping young man, Santos passed the bar in 1955 with high marks. He joined “The Firm” of the time—a reference to the John Grisham novel and blockbuster movie about a group of brilliant lawyers with a Mafia money launderer as a client. Local media people now use the term to describe a partnership of influential legal eagles.

One associate in the law office was Juan Ponce Enrile, who would later become defense secretary and head of the triumvirate created during the martial law years that would oversee the multibillion-peso coconut levy fund.

The others were Eduardo “Danding” Cojuangco, president of United Coconut Planters’ Bank (UCPB), and the late Clara Lobregat, head of the Philippine Coconut Producers’ Federation (Cocofed), purportedly the largest organization of farmers, charged with “developing” the industry.

Marcos decree

Enrile, as head of the Philippine Coconut Authority (Philcoa), prepared the decree President Ferdinand Marcos issued in 1973, a year after the declaration of martial law, imposing initially a

P15 tax—later expanded to as much as P100—on every 100 kilos of copra produced that was to last until 1982.

Enrile also devised the scheme under which the government, in the name of 1 million coconut farmers, acquired majority of holdings of First United Bank from the grandfather of President Aquino, using the levy fund. It became UCPB, and it retained its private character.

UCPB was supposed to provide a permanent solution to the credit problems of the farmers, but its operation was regarded as unusual: public funds were normally administered in a bank owned and managed by the government.

A state audit later revealed that a total of P9.6 billion was collected during the nine years the copra tax was enforced. Critics put the figure at up to P200 billion, saying that in the rural areas there was no way to check declarations by copra traders and millers.

FOUR DECADES That’s how long Oscar Santos and other leaders of coconut farmers have been trying to recover assets illegally acquired using the coco levy. GRIG MONTEGRANDE

The levy allegedly funded showcase circuses of the “smiling martial law” regime—the Miss Universe Contest, the zany World Chess Championship between Anatoly Karpov and Viktor Korchnoi, and the Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier “Thrilla in Manila.” It became the source of fabulous wealth for the Marcos cronies.

No benefit to farmers

No significant benefit went to the farmers. Because of its oppressive character, the program also fed a simmering communist insurgency.

“I personally knew young people, some of them my philosophy students and Cocofed scholars in Xavier University, who joined the National Democratic Front, the Communist Party of the Philippines, and the New People’s Army to protest the injustice of the levy,” wrote Tony La Viña, dean of the Ateneo school of government.

On July 21, 1982, the late Emmanuel Pelaez, a former senator and Vice President, was ambushed and critically wounded while returning home at night. His driver was instantly killed. Pelaez later said the attempt on his life was prompted by his strong stand against the levy. A month after the incident, which was never solved, Marcos scrapped the tax.

Pro-bono lawyer

A native of the coconut-producing heartland, Santos did not stay very long in The Firm with Enrile.

He was the preferred lawyer of laborers and slippered farmers, who felt embarrassed going to his air-conditioned law office, seeing all those Spanish and American associates. And so he quit. A turning point was when he took up the celebrated “Whitecliff” land-grabbing case, winning it for the 434 farmers who turned 2,200 hectares of a forested sprawl in Bondoc Peninsula into farmlands.

He had earlier in 1967 succeeded in overturning the cancellation of the results of 1,051 medical board examinees accused of cheating. He refused to be compensated for his services, accepting only baskets of fruits from the farmers, and from the new doctors a pledge that they would heed his call that they offer free medical services to the destitute.

It became inevitable that Santos would become embroiled in the “coco levy” controversy—as a pro-bono lawyer, a lawmaker as in the Marcos-created parliament and later in the reborn House of Representative upon the ouster of the dictator. He was always at the forefront of a movement that included former Sen. Wigberto Tañada and the late Jovito Salonga to recover the assets.

For benefit of farmers

“Imagine, for every P250 earned from copra, the farmers gave up P60 as tax. It was big money at a time when the daily wage was P4 per day,” Santos said.

“But it’s not just about money, it is about justice,” he said in an interview in a modest townhouse unit, seated behind book shelves filled with folders of documents of his crusades.

“Can you imagine the lost opportunities for the farmers. How many could have graduated from high school with that money. How many could have bought medicine and saved malnourished babies, the sick and the dying.”

One night in the 1980s, Santos reviewed presidential decrees and letters of instruction issued by Marcos concerning the levy. Before he fell asleep, he had found the phrase “for the benefit of farmers” 82 times in the documents that sought to justify the perpetration of the scam.

The poor farmers, now numbering 3.5 million in 25 million households with an income of P50 per day, never benefited significantly from the levy fund.

The last time Santos read the lofty goal was in the Supreme Court decision on 24 percent of shares of stock of San Miguel Corp. (SMC)—part of 51 percent of the securities in one of the country’s largest diversified conglomerates acquired using the fund in 1983.

The ruling handed down in September 2012 after three decades of litigation said that the SMC shares, worth P71 billion, belonged to the government to be used “for the benefit of the farmers and development of the industry.”

Earlier, in April 2011, the high tribunal ruled that another 20 percent of the SMC shares—worth around P80 billion—belonged to Cojuangco, saying that the government had failed to prove that he had illegally acquired the shares and that he was a Marcos “crony.”

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Conchita Carpio Morales described this decision as the “the biggest joke to hit the century.”

Common decency

Morales, now the Ombudsman, pointed out that Cojuangco, as president of UCPB, was “in such fiduciary position [that he] cannot serve himself first and his cestuis (beneficiaries) second … he cannot manipulate the affairs of his corporation to their detriment and in disregard of the standards of common decency.”

The SMC portfolio represented only a portion of the assets purchased with the coconut levy. The other assets, including UCPB and half a dozen oil mills and trading companies, are worth around P30 billion.

Discovery of the SMC stock certificates in the vault in Marcos’ room in Malacañang after he was ousted in the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution prompted the creation by President Corazon Aquino of the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG). In the first executive order she issued, President Aquino directed the sequestration and recovery of illegally acquired assets of Marcos and his cronies.

Season of atonement

After 30 years, the PCGG has recovered more than P170 billion of the alleged ill-gotten wealth of the Marcoses and their associates—estimated to be between $5 billion and $10 billion. The 24 percent of SMC shares represented the largest single item in the PCGG’s recovery efforts.

Cojuangco, who fled with Marcos to Hawaii after the strongman’s ouster, averred in one paid newspaper ad that he acquired his 20-percent bloc from Enrique Zobel of the Ayala business empire, for $49 million, using borrowings from various sources, including UCPB, that he had repaid. He disavowed being a “close associate” of Marcos in the pejorative term associated with a partner in crime.

Other Cojuangco properties are being pursued by the PCGG, including the sprawling Bugsuk farm in Palawan used for a disastrous P100-million seedling program to propagate a Malaysian-West African (Mawa) coconut variety for replanting in 2 million of the country’s 3.2 million coconut farms.

The 24-percent bloc of SMC shares worth P71 billion had been redeemed by San Miguel. The amount is in the National Treasury in the meantime that the government has not decided what to do with it. Vultures lurk in the shadows, scheming to prey on it once more.

“The calvary continues for the farmers,” said Santos, still spry and sharp at the age of 86. “The fight goes on.”

Role for Enrile

Enrile, 92, could play a role in securing justice for the coconut farmers.

A love child born on Valentine’s Day, Enrile was raised as a fisherman. He came to Manila as a first year high school at the age of 21 to look for his biological father. He told him he wanted to finish his studies. He got his wish, passed the bar with a perfect score of 100 percent in mercantile law, went to Harvard and became the second most powerful man in the country as martial law administrator.

Santos came face to face with Enrile during a Senate hearing in December 2011 on a proposed legislation seeking to implement the Supreme Court decision on the disposition of the P71-billion SMC portfolio in this season of atonement. He had vowed he would not allow the levy fund to be plundered this time around.

Next: New President will decide fate of levy assets