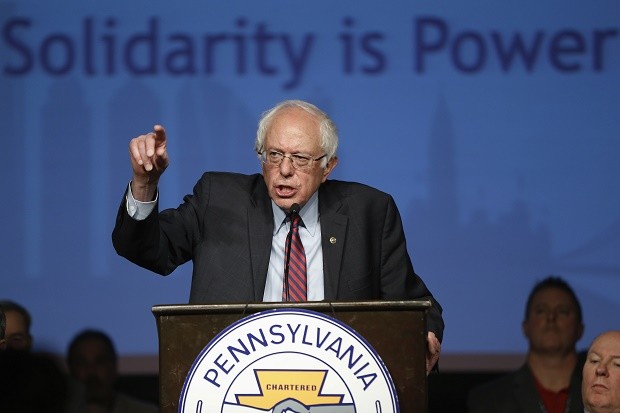

Democratic presidential candidate, Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vt. speaks during a campaign stop, Thursday, April 7, 2016, at the Pennsylvania AFL-CIO Convention in Philadelphia. AP

WASHINGTON — The standard line in Bernie Sanders’ campaign speeches goes like this: “Despite what the corporate media is telling you, there is a path to the nomination.”

If such a track exists, it’s far from clear what it is. Sanders is far behind Hillary Clinton is the race for delegates that will decide the nomination, needing to win 68 percent of those remaining to capture the nomination. Even after his recent run of success, he’s nowhere near that pace.

And it’s not the corporate media he should be blaming, but the rules of a Democratic Party he only recently joined after serving decades in public office as an independent.

The party has tailored its nominating process specifically to prevent an upstart candidate such as Sanders from winning it’s nomination for president. And Sanders’ top adviser, by the way, is a longtime Democratic Party insider helped write those rules.

READ: Clinton, Sanders clash as campaigns shift to New York

How it works

One word: Delegates.

Not states won, not debate triumphs, not cash raised. Certainly, not what the Sanders campaign calls “momentum.”

The nominating contest is about winning 2,383 delegates, and the delegate math says Clinton is decidedly ahead of Sanders.

The basics: All Democratic contests award delegates in proportion to the share of the vote — so even the loser gets some.

That makes it hard for a front-runner to collect delegates and clinch the nomination as quickly as when the winner takes all. But the proportional system also makes it difficult for a trailing candidate to catch up if he or she falls behind by a large number.

Clinton was able to amass a big delegate lead — at one point more than 300 delegates — by winning by large margins in the South, where there are large minority populations that largely back her over Sanders.

In contrast, Sanders has mostly won smaller states that hold caucuses or won narrowly in larger states such as Wisconsin and Michigan, which has limited the number of delegates he’s netted in his effort to catch up to Clinton.

To date, Sanders trails Clinton in total votes cast and by more than 200 delegates. In 2008, when Clinton trailed Barack Obama by more than 100 delegates, she was never able to catch up to him.

The current count: Clinton has 1,280 delegates won in primary and caucuses to Sanders’ 1,030.

What about superdelegates?

Another factor: 15 percent of the delegates who get a vote at the Democratic National Convention are superdelegates, or elected officials and party leaders who can back any candidate they wish.

They are the party establishment. And they overwhelmingly support Clinton.

The Associated Press surveys those superdelegates and adds them to the tally if they say publicly who they plan to vote for at the convention. The AP doesn’t count those who say they’ve decided, but aren’t willing to say so “on the record.”

Clinton’s strong support among superdelegates widens her lead even more — 1,749 to Sanders’ 1,061.

How it got this way

For decades, the leaders and activists of the Democratic Party struggled to control its presidential nominating process. The back-and-forth gave birth in 1984 to the superdelegate.

They are insiders and political pros who are not bound to any candidate, and they act as deciders in prolonged nomination fights.

The original idea was to give party elders a voice in the nominating process to avoid a repeat of what some viewed as a mistake in the 1972 election, in which George McGovern won the nomination but proved to be a weak general election candidate. He lost 49 states in the November vote.

In 1984, under the superdelegate system, former Vice President Walter Mondale was the choice of the Democratic establishment and won the party’s presidential nomination. He, too, lost 49 states in the general election.

Sanders’ superdelegate connection

Tad Devine, Sanders’ top adviser and a Democratic Party veteran of more than three decades, helped craft the superdelegate process.

He’s been quoted defending it — “It’s pretty hard to win a nomination in a contested race and almost impossible to win without the superdelegates,” he observed in a 2008 interview on National Public Radio — and also pointing out that there’s a danger of backlash if superdelegates wield too much power or operate in a less-than-transparent way.

Devine told AP last month that the Sanders campaign expects the superdelegates to choose a candidate “after the voters have spoken — not before.”

READ: Sanders questions if Clinton is ‘qualified’ to be president