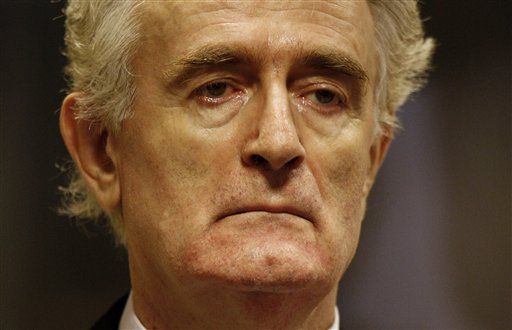

FILE – In this Thursday July 31, 2008 file photo, former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic stands in the courtroom during his initial appearance at the U.N.’s Yugoslav war crimes tribunal in The Hague, Netherlands. More than 20 years after Bosnia’s war, Radovan Karadzic will learn his fate on Thursday when U.N. judges deliver verdicts in his genocide and war crimes trial. (Jerry Lampen/Pool via AP, File)

SARAJEVO, Bosnia-Herzegovina — Mirsada Malagic won’t be celebrating if former Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadzic is convicted and sentenced to life Thursday in his genocide and war crimes trial at a U.N. tribunal.

Whatever the outcome of the case, Malagic says Karadzic has already sentenced her to a life of mourning. Bosnian Serbs forces killed her husband and two sons during the brutal 1992-1995 war. And now, more than two decades later, she says Karadzic’s legacy makes it virtually impossible for Muslim Bosniaks like herself to return permanently to their homes in the part of the country now under Serb control.

Karadzic is still treated as a hero there despite being charged with orchestrating atrocities by his forces throughout the Bosnian war. He is blamed for a deadly campaign of sniping and shelling in the capital, Sarajevo, and the 1995 murders of 8,000 Muslim men and boys in Srebrenica. The conflict left 100,000 dead and forced more than 2 million from their homes.

Malagic, 57, testified against Karadzic during his trial at the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia at The Hague, Netherlands.

“He felt no pain. No remorse. He was actually trying to blame us,” Malagic said recently, looking back at her questioning by Karadzic, who defended himself.

During her questioning, she said, Karadzic claimed she was lying and that thousands of other Srebrenica widows and mothers had buried empty coffins just to make him look bad.

The U.S. brokered a peace agreement to end the war divided Bosnia into two ministates — one shared by Muslim Bosniaks and Catholic Croats, and the other run by Christian Orthodox Serbs, which Karadzic named “Republika Srpska.” Malagic’s village of Voljavica ended up in the latter.

Although the peace agreement guaranteed refugees the right to return, Republika Srpska authorities put measures in place so going home became nearly impossible, or at least unpalatable, she said.

“If you wanted to reclaim your own house, you had to ‘legalize’ it, whatever that means. The procedure cost over 300 euros,” she said, stressing that it was an amount few people could afford to pay.

“They would fix the water pipelines to the village, but those would stop at the street sign saying Voljavica. They wouldn’t go all the way to the houses.”

Of the 1,375 Muslim residents of the village, only about 100 returned. The others were either dead or fled abroad. Those who did return couldn’t find jobs, and their children were taught about the heroic deeds of Karadzic and his comrades in schools. Malagic lives at her sister’s apartment in Sarajevo, often visiting her house in Republika Srpska to check on its condition. But she’s too uncomfortable to stay for long periods.

More than 20 years after the end of Bosnia’s war, Karadzic will learn his fate on Thursday when U.N. judges deliver verdicts in his trial at The Hague, Netherlands. Judges have taken more than a year to deliberate and reach verdicts on the 11-count indictment. Prosecutors have requested life imprisonment.

In the Bosnian Serb ministate carved out after the war ended, his trial is seen by his supporters as an international plot against Serbs and their hero.

Last weekend, current Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik opened a student dormitory named after Karadzic and had Karadzic’s daughter and wife unveil the plaque.

Speaking at the opening, Dodik called the trial “humiliating” and said those who fail to understand why Karadzic is hailed this way are “shallow-minded.” His words were followed by resounding applause.

Karadzic’s forces kept Sarajevo besieged for 44 months, starving and terrorizing it with random bombardment and sniping that took the lives of over 11,000 residents. He was tried on numerous charges, including two counts of genocide related to the expulsion of hundreds of thousands of non-Serbs from seven Bosnian towns and villages and the Srebrenica massacre, as well as, the kidnapping of 284 U.N. peacekeepers who were used as human shields to prevent NATO bombings of his troops.

His goal was to remove non-Serbs from as much of Bosnia’s territory as possible and make it part of a “Greater Serbia.” His successors to this day are still promising Bosnian Serb secession.

Karadzic was indicted in 1995 but evaded arrest until he was captured in Belgrade, Serbia, in 2008. His trial in The Hague started in October 2009 and three years into it Malagic received two phone calls within a few days.

The first was an invitation from the tribunal to testify against Karadzic. The second came from a DNA lab, informing her that her 19-year-old son Elvir was identified among the skeletons of a Srebrenica mass grave. In the courtroom, she felt surprisingly good.

Malagic said she has been on sedatives every day since 1995, noting “the only time I felt I did not need the pills was when I testified.”

In her testimony, she detailed how the family fled to nearby Srebrenica as Karadzic’s troops expelled them from her village in 1992. In July 1995, her family had to flee again when Serb troops overran the town. Malagic described the screams and the chaos in which her family members lost each other and how — although pregnant and injured by bombs the troops sent after the fleeing civilians — she still managed to hold on to her 10-year-old son Adnan and escape to the government-held town of Tuzla.

She delivered her fourth child, daughter Amela, the next January when the war was over and kept searching for her husband and two sons she lost in the melee.

In 2009 forensic experts found the skeletons of her 15-year-old son Admir and her husband Salko in mass graves. She buried them in 2010.

After the war, Muslim Bosniaks tried returning to their villages controlled by Bosnian Serbs. Many eventually left again after finding jobs or sending their children to study abroad. They decided to keep their addresses in Republika Srpska, come home for holidays and wait for better times to return for good.

“Radovan Karadzic was tried, (but) not his project called Republika Srpska. That stays and hampers every progress of this country,” said Fadila Memisevic, a human rights activist and head of the Bosnian branch of the German Society for Threatened Peoples.

As an example, she points to a current problem with a 2013 census in the country. The results are still not published because the Serbs demand that those who are registered at addresses in Bosnia but work or go to school abroad be stripped of their residency status.

Effectively, this would administratively erase more than 400,000 mostly Muslim Bosniaks from the region.

Karadzic insisted after the war that no more than 5 percent of non-Serbs should be allowed to return to Republika Srpska, Memisevic claims.

“So what else is this demand about than implementing Karadzic’s plan?” she asked. “There is no reason to celebrate this verdict, even if he is locked up for life.”