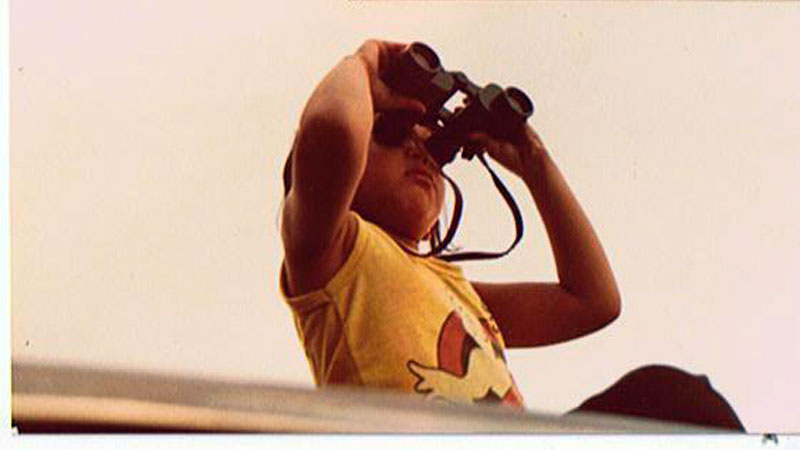

CHILD OF THE REVOLUTION The author—or her “excited 5-year-oldme”—scans the Edsa crowd from atop the family car on Feb. 24, 1986. PHOTO BY TONY VILLAFUERTE

I WAS only 5 when the 1986 Edsa People Power Revolution happened.

All the while, I had an inkling that something was going on, something really big and important. But like any 5-year-old, my main concerns were watching cartoons and playing with other kids in the neighborhood. Yet, as most kids my age go, I was also big on listening in to what the grown-ups were occupied with, and asked incessant questions.

Weeks before Edsa happened, I overheard my parents talking excitedly, but also looking grim. They were talking about goons, supporters of then President Ferdinand Marcos, who had barged into a school that was being used as a voting precinct during the snap elections. Fortunately, people from the National Movement for Free Elections got to the school on time. A scuffle broke out between the two groups and my father, who was helping guard the ballot boxes, was right there.

Days later, on the night of Feb. 22, when Butz Aquino and Cardinal Sin urged people to go to Edsa to protect the rebel soldiers holed up inside Camp Crame, my parents were out of the house in a flash, even before my grandparents could protest. My mom and dad were gone for hours and came home looking soiled and dirty, like they had come from the mines. It turned out they were hauling and lining sand bags along Edsa to block Marcos tanks in case they tried to disperse the people.

Water station

On Feb. 24, my parents decided to take me with them to Edsa. They packed the car with the essentials, sleeping mat included. Of course, 5-year-old me was excited! Finally, I would get to see what we had been monitoring on the radio, I’d get to see what my mom and dad had been talking about.

We parked in front of the V. V. Soliven building along Edsa: my parents, my maternal grandmother, a cousin, an aunt who was celebrating her birthday that day, and a doctor uncle. The grown-ups turned the car into a first aid and water station and took turns disappearing into the thick crowd to gather updates on the situation.

My dad put me on top of the car and handed me a pair of binoculars. I was to scan the crowd from time to time for people we know. Of course, if you were 5, you’d feel like you had been assigned a very important job, as if you were a pirate on a mission. Besides, it was not every day that I was allowed to stay on the roof of the car. My dad’s rules on how to treat the car were being thrown out the window—yeees!

Now, thinking back, I realize that maybe my father just wanted to keep me occupied. Parents then needed to be more creative to keep their kids from wandering off at a time when tablets and smartphones were unheard of.

False alarm

For hours, I sat on our car’s roof with my trusty binoculars, looking out to the sea of people. I remember helping hand out drinking water to strangers, feeling like I was a part of the whole thing, too. I can’t remember if I ever felt afraid. Probably not.

When we got home that night, we got word that the Marcos family had left Malacañang, but it turned out to be a false alarm. We went back to Edsa the next day.

Years after the Edsa Revolution, my dad would kid that they had decided to take me along to Edsa so that in the event that something bad happened to them (read: they die), I wouldn’t be left an orphan. Yes, so that we’d all die together.

Looking back, I’m glad my parents took me along at Edsa, and that I was old enough to remember and appreciate what took place.

I asked my dad if he would do it all over again—risk his life to stand up against a tyrant. Without a moment’s hesitation, he answered, “Yes!”