Duterte’s mass movement

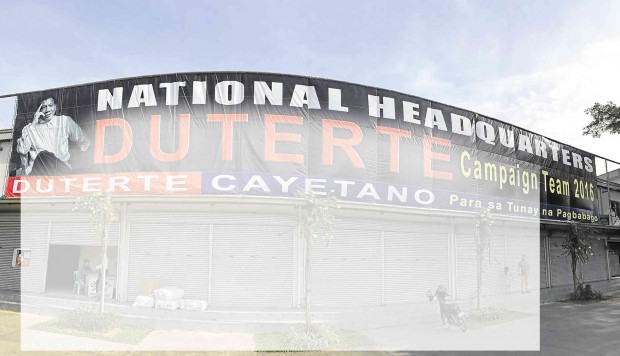

Duterte’s national headquarters in Davao City, where his campaign coordinators and supporters meet NICO ALCONABA

To his supporters, Mayor Rodrigo Duterte’s proclamation activities on Tuesday were a preview of how his presidential campaign would be run in the next three months.

The tough-talking Davao City mayor was at his proclamation rally in Tondo, but similar activities were held elsewhere in the country.

Leoncio Evasco, mayor of Maribojoc town in Bohol province and campaign manager of Duterte, said Tondo was chosen as the venue for the main rally at the start of the campaign period “to dramatize the plight of the urban poor.”

But Evasco said Tuesday’s activities were just a preview of what would happen in the coming days.

“It will be unconventional,” said Rocky Balili, campaign coordinator for Southern Mindanao.

Since most members of Duterte’s Mindanao group are former activists, some even former cadres of the Communist Party of the Philippines, his campaign will have a semblance of a mass movement.

“There will be fewer rallies, but more caravans in communities,” said Evasco, a political detainee during martial law.

For Duterte’s camp, it will be more practical, financially and security-wise, to go around communities to meet people as holding political rallies will be like gathering sure supporters of the mayor.

“In these caravans, we will be able to talk to people, make them understand why we need a Duterte presidency,” Balili said in a separate interview.

Balili said they would also encourage people to produce their own campaign materials.

“This is what happened on Tuesday—people made their own placards and streamers. Most of them made placards out of recycled sacks,” he said.

Balili said they also urged people with resources to set up places where people could go and have their shirts printed for free.

And like mass movements, there will be organizing. Local campaign coordinators have since been going around provinces and towns to talk to groups.

The plan, Balili said, is to form confederations of already-organized groups of farmers, fishermen, women councils and others.

“It’s not hard to convince them because they are pro-Duterte to begin with,” Balili said.

He added that in the next three months, coordinators would organize supporters in the barangay and sub-barangay levels.

“This will ensure that we will have watchers come election day,” he said.

But the Duterte candidacy has, in a way, changed how elections are held.

Joel Mamac, who was regional coordinator of former Sen. Manny Villar when he ran for President in 2000, said he was surprised to see a lot of volunteers for the Duterte campaign.

“These people bring their own food during assemblies. They know the Duterte camp does not have money to provide them with free lunch,” Mamac said.

“People also volunteer to transform their homes and spaces into campaign headquarters,” he said.

Allan Libante, a Bukidnon-based coordinator, said he did not have a hard time organizing supporters down to the barangay level because people were willing to give their time for the campaign.

“All they want is total change,” Libante said.

As for campaign materials, Libante said, there are sponsors willing to shoulder the expenses.

“These sponsors directly pay the printers of stickers,” he said.

“We don’t expect that the funding will come from the Duterte camp because we know our candidate has no money,” he added.

For Mamac, the Duterte candidacy has somehow reversed what used to be the norm—local candidates asking financial support from visiting presidential candidates.

“This time, we in the Duterte campaign are the ones asking for their help,” Mamac said.