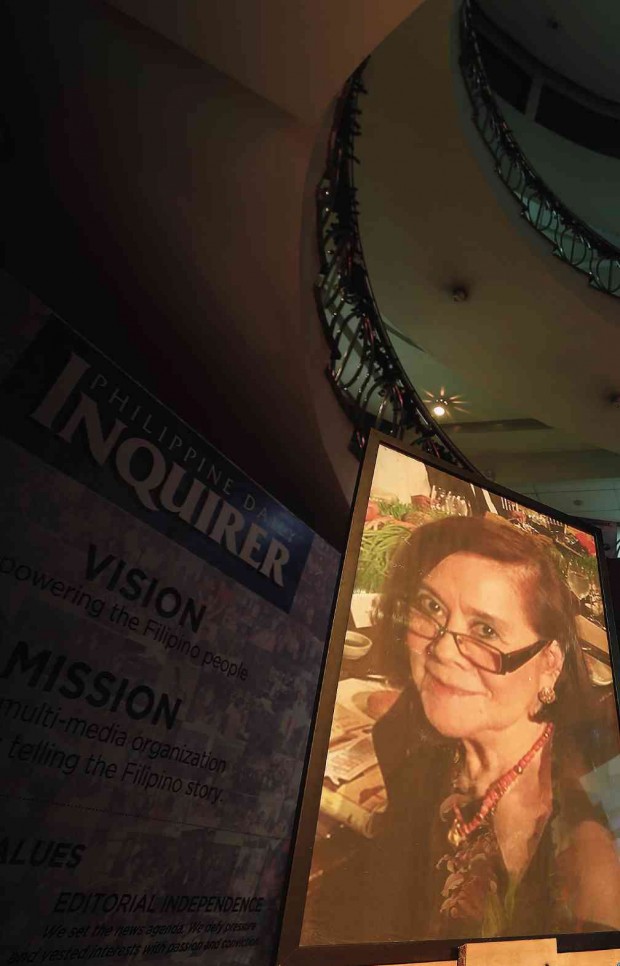

“By the way, don’t call me Madam. Call me Your Imperial Highness,” was Inquirer editor in chief Letty Jimenez-Magsanoc’s closing words in a letter explaining how the central desk decides on which stories to use on Page One.

The sarcasm was in reaction to a complaint that most of the stories that landed on the newspaper’s front page were about Manila and were chosen by “Imperial Manila” editors.

It was in the 1990s, and Ma’am Letty, or LJM to most in the Inquirer, got irked by the accusation that she ended her letter in such a way. We never called her “Your Imperial Highness.” We got stuck with “Ma’am,” that sometimes sounded more like “Mom.”

For all the years she would make late-night calls, she was more like a “Mom” than a “Ma’am.”

“Nice job,” she would say.

“Is it safe for our correspondents?” she would ask.

Bureau reporter Julie Alipala recalled getting her first phone call from LJM in early June of 2001 while in Basilan province covering the kidnapping of foreigners from the Dos Palmas resort in Palawan province.

“Hello, is this Julie? Julie Alipala? This is Letty, Letty Jimenez-Magsanoc. You see, I am reading your story right now about this emissary. Tell me who this emissary you quoted in your story. I have to know because I have spoken with the President (Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo) and I have some information,” LJM had said.

Alipala obliged, giving the name of her source.

“I thought she doubted my access to A-1 sources. She asked for phone numbers and they spoke over the phone. I pleaded to her to protect my sources. She assured me, ‘Every secret is safe with me,’” Alipala said.

Verification

More than an hour later, LJM called back.

“Julie? Julie? Letty here again. Great job. Your source is the same person Arroyo spoke with,” LJM said.

“After that day, her voice became a regular sound to my ear, usually midnight or early dawn. She made calls to double-check sources, to ask if I am still safe (especially if I was assigned to Basilan or Sulu). As always, two calls, and the last would always be, ‘Good job, keep it up, kiss your baby for me,’” Alipala said, recalling her phone conversations with LJM.

The last time Alipala saw LJM was last year.

“I saw her at the newsroom, flipping pages. She was making hand signals (which I failed to read). I was also trying to catch another puff. When I got back, all she said was, ‘I did it (quit smoking), why can’t you?’” Alipala said.

Alan Nawal, the assistant bureau chief, said that although seeing LJM every day was impossible, she was “every bit and inch a mother.”

“Sometimes, she would relay her messages through other editors, but I could feel her motherly and friendly love,” Nawal said.

Cotabato City-based correspondent Nash Maulana recalled talking to LJM the first time in September 1994.

“We were talking on the phone (landline) about her daughter Kara’s planned trip to Maguindanao province then. The main itinerary of Kara and her team was Camp Abubakar, at the time when travel to and from the camp and Cotabato City was not possible for a day’s round trip. This was because of bad roads and the unavailability of transportation from Barangay Lancong in Matanog town to Abubakar proper and back. (The paving of Camp Abubakar’s main interior road started in 1995),” Maulana said.

Worries

“Would it be safe for you there, Nash, tingin mo, and with Kara and her team (of foreign journalists)?” Maulana recalled LJM asking him.

“There were no mobile phones yet then, and I could imagine her motherly worries for an only daughter literally off to a battleground when they could not anymore reach each other on the phone the night we slept in Camp Abubakar,” he added.

On their return to Cotabato City the afternoon of the next day, Maulana immediately went to a public telephone booth to place a call to LJM to report that everything was fine.

“Thank God you are safe with Kara and her companions there, Nash,” LJM told Maulana.

But there are correspondents who have no encounters with LJM.

“It’s one of regret, and it felt almost the same as the passing of all the other great writers, such as that of NVM Gonzales years ago. You hear that a great writer has passed away and you feel you have not even talked to him/her as much as the others, you feel deprived,” said bureau correspondent Germelina Lacorte.

“But on second thought, you realized she hadn’t really died in the real sense of the word because you still have access to her writings, and the things that she did are in the stories that are being told and retold, and so, she lived and you feel consoled,” she added.

Rare encounters

Tagum City-based correspondent Frinston Lim said he felt the same.

“It would have been a good thing if I met her as I turn 10 years being in the Inquirer,” Lim said.

For Lacorte, LJM’s story will continue “to light the path for the continuing struggle for press freedom in the country known to be among the world’s most dangerous places for journalists to work.”

“In the light of the relentless attacks against journalists, the pervasiveness of political dynasties and warlordism, she will continue to inspire new generations of journalists who may or may not even know her personally,” she added.

Nawal, who met LJM only twice, said each encounter—even if they lasted for only a few minutes—was “a treasure to hold.”

“My first one-on-one meeting with LJM was when I was called to Manila for my interview as a desk editor for Mindanao. She told me that it would be one hell of a job because Mindanao is unlike other areas,” Nawal said.

“You have all sorts of problems there,” he quoted LJM as telling him, adding in Visayan: “You have many good things there that are of human interest.”

“LJM told me there are a lot of stories that needed to be told about Mindanao beyond the daily incidents of clashes, kidnappings and other forms of violence,” Nawal said.

‘Long live the Chief’

For Bayan Muna Rep. Carlos Isagani Zarate, “no paeans, not even thousands of front-page column inches can possibly express—fittingly—the immense contribution” of LJM in the causes of press freedom and democracy in our country.

“As the chief of the Inquirer, among others, she will also be remembered for giving particular attention to the news coverage of Mindanao—helping the nation at large, in the process, to know and understand the island’s stories and narratives—not only the stereotyped reports of violence, but, more importantly, the struggles and triumphs of its peoples,” Zarate said.

“Mindanao’s priority on the pages of the Inquirer is also highlighted by the establishment of a full bureau complement with staff members and correspondents scouring for stories of this often neglected island of many lakes and its quest for a just and meaningful peace,” he added.

“Of late, for instance, the Inquirer has highlighted and come out with stories, including an editorial, on the plight of the Mindanao lumad (indigenous peoples) being displaced by continuing militarization, paramilitary atrocities and the entry of destructive development,” said Zarate, who was part of the Inquirer family as a columnist for Kris-Crossing Mindanao from 2001 to 2013.

“The once-a-week Kris-Crossing Mindanao column has become a platform for us ‘provincial’ columnists to highlight our advocacies, particularly in highlighting the voice of the poor and marginalized tri-people of Mindanao: the lumad, the Moro and the settlers,” he said.

And, Zarate gives LJM a new title—the Chief.

“Yes, a big void the Chief has left behind. Yet, the Chief will be remembered,” he said.

“The Chief is dead! Long live the Chief!” he added.