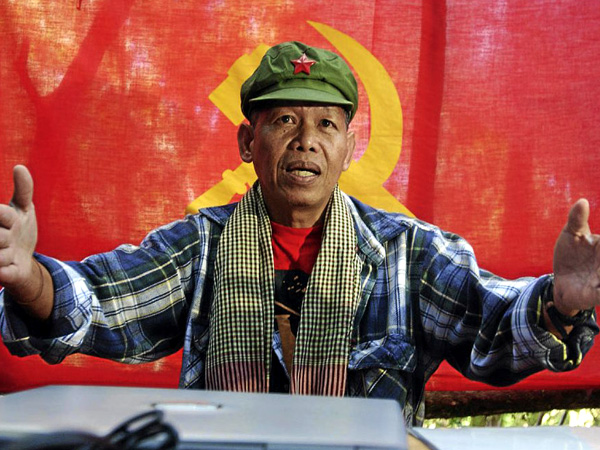

Ka Roger still a long way from home

The life that Gregorio “Ka Roger” Rosal wanted to change may well have been his family’s.

The life that Gregorio “Ka Roger” Rosal wanted to change may well have been his family’s.

The son of a rice farmer, Ka Roger had told his family that they should have been firm in owning the portion of an hacienda where their father worked as a tenant for 28 years, according to his younger sister, Felicidad Rosal Inandan, 61. The Rosals are natives of Ibaan town in Batangas.

Felicidad, who has been sewing curtains and pillowcases for a living in Barangay Talaibon in Ibaan, remembers her brother, former spokesperson of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). On Sunday, the CPP formally announced the death of Ka Roger from heart attack on June 22, or four months ago, at the age of 63.

“No equivalent in money,” Felicidad recalls her brother saying in Filipino of the money given by the heir of the hacienda owner for the piece of land that their father and other tenants tilled.

In 1942, Pablo Rosal, Ka Roger’s father, started to work in the hacienda of Dr. Daniel Reyes, a dentist and once the wealthiest in Ibaan. Pablo quit in 1970 due to illness and until his death in 1982 at the age of 71, he never got to own land.

His mother, Crispina, sewed clothes and mosquito nets. She died in 2006 at the age of 92.

Reyes’ heir, an adopted daughter whom Felicidad did not name, refused to give away the portion of the hacienda to Pablo’s children. She instead offered to pay them an amount which Felicidad could no longer remember.

Ka Roger was then already with the underground communist movement, his sister says.

Mosquito net peddler

Ka Roger was born in Talaibon on April 19, 1948. He finished elementary at Ibaan Central School and high school at Saint James Academy.

He was second honor in elementary and third honorable mention in high school, Felicidad says. He pursued a Bachelor of Arts in Commerce degree at Golden Gate Colleges but failed to finish when he joined the armed group, she says.

She says her brother was always a group leader in school and in their barangay. He even organized the Santacruzan, a popular religious May festival, in the villages.

“He helped the family by working with our father in the farm and in peddling mosquito nets and blankets in Parañaque when he was still a student,” Felicidad says.

In 1972, at the age of 20, he joined the revolutionary movement. “All of us in the family, especially our parents, forbade him from joining, but his will triumphed,” his sister says.

A different life

Then life became different for the family, she says. “We, especially our parents, were always worried. Our mother always cried during the initial months when he was in hiding.”

Ka Roger joined the communist New People’s Army because of threats to his life after he joined a demonstration against the dumping of pig and chicken manure in a stream leading to the Ibaan River by a businessman. It was his first demonstration and he became a wanted person to the military, Felicidad says.

He was invited to Camp Salokot (now Camp Malvar in Batangas City) by the military but was detained instead and brought to Camp Vicente Lim in Laguna. According to Felicidad, he refused to get a “kumpadre” inside the camp as what the family wanted so he could be freed. It was unnecessary, he said, and besides, they didn’t have money to spend.

Ka Roger escaped sometime in 1976.

Even if he did not heed the pleas of their parents against joining the NPA, Felicidad says she believes he truly loves them. As a brother and son, she describes him as “protective, courteous and thoughtful.”

Ka Roger has two daughters, one of whom also joined the NPA. Felicidad has no idea on the whereabouts of the other child.

Last contact

Felicidad last met her brother in 1997 during the CPP’s founding anniversary celebration in the Sierra Madre. The party was founded on Dec. 26, 1967.

“Every year, he would arrange for us (sisters and parents) to travel and meet him in the jungle,” Felicidad says.

She recalls Ka Roger’s words in Filipino to their mother, Crispina, that left an imprint on the family: “Mother, you will come to finally understand what we are fighting for.

In May 2006, Crispina died. Her wake was the last time the family spoke to Ka Roger.

When radio communication was tightly monitored in 2006 during the time of then President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, Felicidad says her brother had told them that he was restricted from calling them for security reasons. “I never heard a word from him,” she says.

She says she learned of her brother’s death on Sept. 24 through a letter dated Sept. 23 from the CPP’s Information Bureau, which was handcarried by a rebel courier. The mail, however, did not disclose where he was buried.

The messenger, who came with a male relative of the Rosals, disclosed that the rebels were planning to bring the remains of Ka Roger to Ibaan, but did not say exactly when.

“I’m thankful with their plan of bringing his remains, I’m just hoping it would be soon. I have only one prayer and that is to see his body,” Felicidad says.