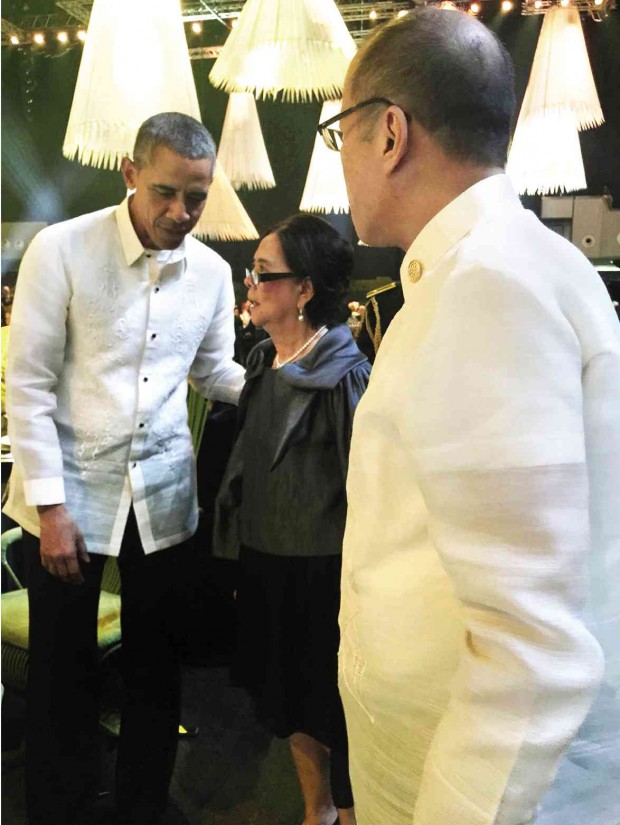

PRICELESS MOMENT In a bold spontaneous move, Letty Jimenez-Magsanoc exchanges pleasantries with President Aquino and US President Barack Obama during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation welcome reception dinner in November at SM Mall of Asia Arena. Mr. Aquino reminds Obama that Magsanoc was one of the heroes of the Edsa Revolution. THELMA SIOSON SAN JUAN

THIS is our saddest Christmas, and each day is spent trying to hold back tears as we work in the newsroom.

The men, most of them anyway, try to be stoic. The women, most of them, give each other a tight hug now and then, bury their head on the other one’s shoulder and break into sobs.

This is the hardened newsroom that, as they say, eats death threats for breakfast.

My problem is—I still can’t fully cry. Not yet.

It’s as if, if I did it would be surrendering to the reality that our esteemed editor in chief, Letty Jimenez-Magsanoc—LJM to us and Letty to some—is gone for good.

It was about 7 p.m. on Christmas Eve when I got a text from a friend asking if it was true that Letty “had passed away.” Is this a bad joke, I replied. But the texter asked me to find out anyway.

I called Letty’s house and her kasambahay, in a tearful voice, told me to call Letty’s daughter, Kara, instead; she was at St. Luke’s.

St. Luke’s? We didn’t even know LJM was in the hospital.

I called Joey (Nolasco, our managing editor), who had just gotten home after putting the paper to bed early that evening. Right away, he said no, “cannot be.”

Joey decided we text Sandy (Prieto-Romualdez, or SPR, our president and CEO).

Minutes later, SPR called. I heard cries, not words.

And that was how the Inquirer got its news on Christmas Eve.

LJM passed away late in the afternoon of that day at St. Luke’s Global City, surrounded by her beloved family—husband Carlitos, only daughter Kara, and sons Nikko and Marty. She suffered cardiac arrest.

As late as Tuesday, she was still giving marching orders to some of us. She told me, on the phone, to make sure our story on Pia (Wurtzbach, the new Miss Universe) was given a personal angle, because Pia was, as she put it, “ours” (Wurtzbach is a contributor/stylist/model of Lifestyle’s toBeYou). She was her usual self-ultrapossessive of the news, passionate about the story, except that, I noticed, her voice was weak.

I asked her when she thought she would be in the office. She had wanted to be at work the week before the New Year, because that was her turn (the newsdesk is divided into New Year and Christmas teams, so that they can take turns taking the holidays off), but her back still hurt.

Almost as second thought—not primary thought, because to us Letty was invincible—I asked, you’re still in pain? She said yes, adding it seemed this took time to heal. Age, she said. Perhaps it would take six months before her back fracture could heal; it’s just a slowing down of healing because of mature age, she said.

We would visit you, I told her. “Yes, I would like that,” she said. “Now.”

I took “now” to be a figure of speech, given our hectic schedule. Looking back, I now realize she meant really “now.”

I and the girls never got to visit her that Tuesday or the day after because we were advancing deadlines for Christmas.

Backbreaking pain

Letty had been suffering from, according to her, “backbreaking pain,” and had been on sick leave for about two weeks. During that time, in a text message, she said, an X-ray showed “lumbar 1 and 2 fracture in my spinal column. Because my injury of two years ago acted up, X-ray shows there’s now a tear in my bone.”

She wasn’t feeling well enough to attend the Inquirer’s 30th anniversary celebration on Dec. 9, and looked at it with spiritual resignation. Her text to me read, “You know nothing would have stopped me from celebrating this milestone with you all. There must be a reason why the Lord believes otherwise. As my mother always says, even the falling of a leaf…”

Control of her health

As she did the newsroom, Letty had an almost obstinate control of her health, tempered only by her strong spirituality, even as she was seeing doctors. We learned that even as she was forced by family to go to the hospital last week, she agreed only on the condition that she would be back home to fix the family noche buena.

Hard as we try and talk, we can never fathom the grief and loss her husband and children are suffering.

What matters to us now is, even as she remained oblivious to her increasing frailty and, as it turned out, her failing health—she never let on; she would try hard to stick to the midnight (literally midnight) curfew imposed on her by her family, but would break it now and then and stay in the office way after midnight—what matters to us is, she willed herself to live, the same way she willed herself and her staff to achieve unthinkable feats.

Letty made the Inquirer do the impossible: unseat a President, run an exposé on the pork barrel scam that put behind bars the powers-that-be, relentlessly run stories that impacted the candidacy of a presidential aspirant. The list goes on and on.

The story that is LJM isn’t finished yet.

We now have an onrush of memories of incredible moments.

Apec feat

One of the last incredible feats she put me up to was during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Apec) welcome reception dinner at SM Mall of Asia Arena on Nov. 18. After the Apec economic leaders had taken their seats around the table at the center of the vast venue, led by President Aquino and US President Barack Obama, Letty turned to me and said casually, “I want to observe P-Noy and Obama interact. I want to stand behind them.”

Just an impulse, I told myself. Ignore.

Not ignore. She was repeating it way into the main course. I had to find a way to walk her to P-Noy and Obama, and from behind, to whisper to P-Noy that Letty was behind them.

That produced the memorable shot of LJM between P-Noy and Obama, with P-Noy telling Obama, “You remember her?” and Obama saying, “Yes, from the Edsa Revolution.”

As the eyes around the hall bored through us, I overheard Letty telling Obama that she had his books and asking if he could sign them. That was the second time she did that.

Autograph sought

(The first time she asked him to autograph his book for her was during the state dinner for Obama when she casually walked up to him at the end of dinner.)

“Of course,” Obama said, “I will be staying here until the 20th. Have them brought to my aide in the hotel.”

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing—Potus was giving this woman his schedule. Unable to control my shaking knees, I walked back to my table and wanted to bury my head in the tablecloth, in embarrassment.

I knew what Letty could be after—a quote (what an eavesdropper), an observation, anything that could make the Inquirer’s banner tomorrow different from all the rest. Did she get it?

Last coverage/party

Come to think of it now, perhaps she didn’t care that night if she did. She walked back to our table truly happy. “He actually remembered me,” she said, gleeful like a girl.

I realize now how much LJM—this dragon woman who was supposed to be jaded already after about 40 years in journalism—truly enjoyed that evening’s coverage, as if it wasn’t just a coverage, but a social outing as well.

A woman who never allowed her photograph to be published in her paper, if she could help it (“We are not the news, we cover the news”), she was asking me that night to take her picture. She wanted, she said, to show it to Pepito Albert who made her kimono-like gray top (she was an Auggie Cordero woman, the designer having made her bridal gown, but she didn’t want to bother Auggie this time) and to show perhaps to her family.

I’m now glad I did. That was Letty’s last coverage/party.

Following the story with an angle that was only the Inquirer’s—whether it was a trivial social moment with Obama and

P-Noy or the pork barrel scam, LJM was doing that—fearlessly.

It was as if she didn’t care if she got in harm’s way. If she did, the passion to get the story was bigger than the fear.

She had the spunk and guts but was never in your face about it. Joey loves to quote how Letty had summed up the Inquirer’s task—“Fighting for freedom, with fun.”

Power

She didn’t have to brandish power. One late night, when the remaining staff around the table suggested she write or publish her memoirs, she asked nonchalantly, why, what for? Because, we said, of the many historical moments you were in and your power. She said, if you have power, you don’t need to brandish it … or something to that effect.

She understood power, but she also understood friendships. And interestingly, neither the sense of power nor the pull of friendship could distract her from the pursuit of a story. We have been a witness to some friendships she had lost on account of Inquirer stories.

With elan

She can do an exposé on friends—with elan.

We were having dinner with Vice President Jejomar Binay that night at Coconut Palace. The Vice President had laid out a sumptuous spread, ostensibly to mark my birthday.

Letty was seated beside Binay. At the end of dinner, she turned to him and, in a courteous tone, said, “Mr. Vice President, we just like to inform you that we are running a series on allegations of corruption.”

And she asked the Vice President if his spokesperson would be tasked to answer questions. Binay just said yes.

Spiritual fortitude

Even seasoned journalists are amazed at how well Letty could straddle adversarial role and friendships. If it pained her, she managed the experience well.

This must be because she had a trait not every journalist has—spiritual fortitude. Not only was she pious (she went to Mass every day), she also drew strength from her faith in God and devotion to the Virgin Mary.

In the 1990s, when she and I faced an office problem and I couldn’t stop myself from talking about it, she just said, “Come with me.”

I didn’t know where she was going to take me. She took me to the noon Mass at the Edsa Shrine. That quieted me down.

That wouldn’t be the last time I would join her at noon Mass at Edsa Shrine or at Meralco Theater. It was a ritual we would continue even after I had moved to ABS-CBN Publishing.

She was spiritual and religious. Suffering from pain in the last few weeks, she told me how she got to wearing the St. Benedict medal, as I had told her to. “But pray for me some more,” she would tell me.

LJM stories

This week, the Inquirer continues to run stories and anecdotes from the staff that speak not only of interesting encounters with LJM. The reader will note how these stories have a common thread, aside from LJM’s journalistic expertise.

These stories will speak of LJM’s compassion, which, looking back, I felt grew and grew the closer she was to dying.

You would be hard put to find a staff member in the newsroom whom she did not help—on a personal level, whether it was on a love problem or job or whatever.

At the end of her life, Letty enjoyed the gift of seeing and forgiving a person’s weakness.

In a moment of our grief, a friend shared a thought—Letty had given so much already, to the country and to everyone else. Should we ask for more from those who have given much already? Our prayers should be one of thanks for her life.

Thank you, LJM.