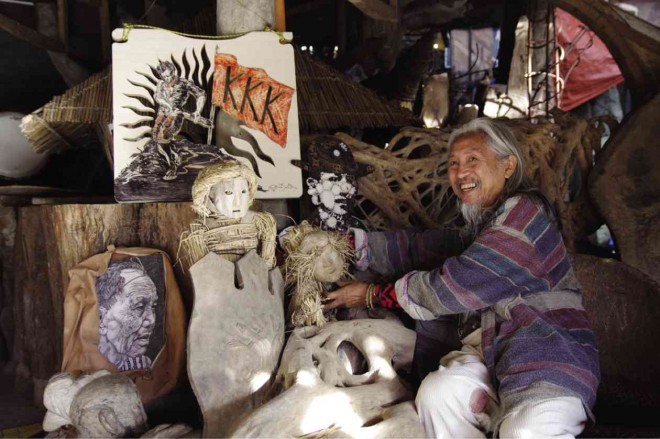

KIDLAT’S ‘BELEN’ Unlike the traditional “belen,” Kidlat Tahimik’s Nativity tableau at his Ili-Likha Artist Village in Baguio City is a pantheon of Philippine heroes. RICHARD BALONGLONG

The sons of independent filmmaker Kidlat Tahimik (Eric de Guia) got their first Bonifacio Day gifts in 1992, 25 days before others in their neighborhood in Baguio City received their Christmas gifts on Dec. 25.

Kidlat’s boys were puzzled as they opened gifts a month ahead of the traditional gift-giving. But years before that, they had been getting their gifts on Dec. 30, Rizal Day, five days after Christmas.

That’s how Kidlat’s family continues to reclaim their very Filipino Christmas by commemorating Philippine historical events and revolutionary leaders.

Kidlat said his Yuletide activities are not meaningless eccentricities. “We are such a Christmas-

crazy country,” he said, making references to radio stations that air Christmas jingles in September. These airings are followed by commercials promoting shopping malls’ pre-Christmas sale.

“We have [television programs] already doing their countdown to Christmas [on Sept. 1]. This is basically a commercial thing. You hype it up, and people stick to [what you are selling] like Pavlov’s dogs (classical conditioning made famous by Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov using dogs). ‘Iba na, eh’ (The Christmas season is different now),” he said.

Different calendar

So he began celebrating a different Yuletide calendar, after giving out his last Christmas gifts in 1985.

The filmmaker said he did not intend to create a Yuletide calendar of his own. But his household has turned up the festivities on Nov. 30, Dec. 30, and Jan. 6, the birthday of Melchora Aquino (Tandang Sora to the revolutionaries of the Katipunan), who was given bicentennial honors by the government in 2012.

Recently, Kidlat was thinking of celebrating the Malolos Constitution, which was ratified on Jan. 21, 1899—“to complete my season,” he said.

The family does not celebrate the heroes but their stories and legacies, which reveal how Philippine revolutions tried to reshape or thwart the cultural and political rules imposed by the colonizers, he said.

“It’s so easy to say we hate America or Spain. It’s easy to raise our clenched fists and shout, ‘Makibaka!’ (Dare to struggle!), but we don’t understand why these [colonial rules and systems, and the problems these begot a century ago] are still with us,” Kidlat said.

An alternative

History and culture make a people united behind certain goals, he said.

The traditions he and his family have built are “not an anti-Christmas season,” he said.

“It’s just an alternative. I think there should be some shared space [for my ideal holidays]. I think Christ would say, ‘Let’s give space to this other idea,’” he said.

He continued: “It was 1985 when I last gave Christmas gifts. You take great pains to select the best gifts [for your kids], and when Christmas came, it was like a bomb exploded in the household with gift wrappers flying out as they went over a deluge of gifts from the grandparents, uncles and godparents.

“They did not even know from whom the gifts came, and I realized, ‘Wow, we have lost the meaning of Christmas.’ It became a commercial habit disguised as this obligation to be considerate, to think of your kids.”

Filipinos have genuine love for family, Kidlat said, “but we still fall for that trap of buying something for them [only on Christmas].”

In 1990, shortly after a powerful earthquake devastated Baguio, Kidlat took a teaching job in the United States, bringing along his sons Kawayan and Kabunyan. They took a road trip to Navajo Indian territory on Dec. 29 and were caught in a severe snowstorm. They had to park the car on the road to wait for the storm to settle down.

Snow blanketed the road and his car. “Then there was this small hand that came out of my car window [as I looked at the side mirror], and a small voice [from one of the kids] greeted me, ‘Happy Rizal Day, Tatay!” Kidlat said.

He said he was delighted to receive an e-mailed greeting on Nov. 30 this year from Kabunyan, who was in Zamboanga. “Sugod mga kapatid! (Charge, brothers and sisters!) Happy Bonifacio Day!” the e-mail said.

“And then I got the same greetings from Kidlat (the eldest son and the filmmaker’s namesake) who was here, and from Kawayan who was in Manila. I’m getting the greetings for what I started—

my season,” he said.

Tsunami of gift-giving

“I’m not making a personal judgment of people who want to crowd into the malls…. I also cannot also stop giving gifts because Christmas is a culture. Regardless of whether it’s colonial, it is here to stay. All I’m saying is can’t we balance it? So I stopped giving gifts on Dec. 25 because the value of a one-on-one interaction [between the gift giver and the receiver] has been lost in a tsunami of gift-giving.”

Dec. 30 appealed to him as the first of many De Guia family gift-giving dates because, Kidlat said, the day dedicated to the martyrdom of Dr. Jose Rizal means one more holiday to extend the vacation week.

“I am not saying don’t celebrate Christmas or New Year. That’s why I am joining the movement [by a Rizalista group] to move Rizal Day to [the hero’s] birthday on June 19. … How can you remember a national hero when the fever [is directed at] Christmas and New Year?” Kidlat said.

“Rizal certainly has been upstaged. Who can beat Jesus Christ?”