PARIS—Four days before the climate change talks in this city are set to end, the mood of the 21st Conference of Parties (COP21) meeting in Le Bourget, just outside this city, is upbeat. Many delegates have expressed optimism that 18 years after the Kyoto Protocol, a new legally binding agreement to reduce carbon emissions is within reach.

But not all share the same sentiment.

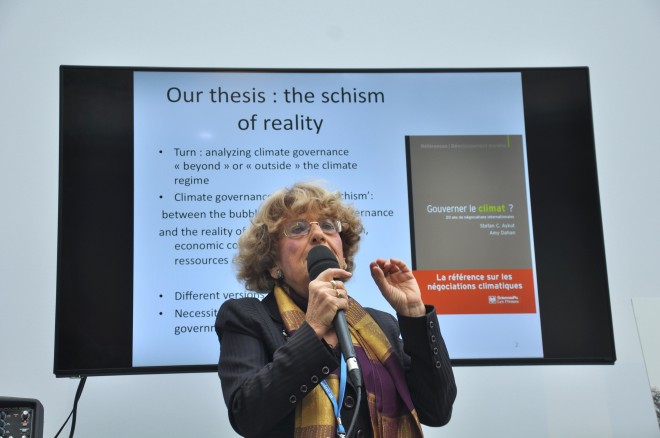

Amy Dahan, senior researcher at Center Alexandre-Koyré, said COP21 should not be framed as the “miracle” many are hoping for, because of persistent problems that stem from the tumultuous political and economic history between developed and developing countries.

“We cannot have too many hopes for this Paris agreement or outcome. It can help a bit, but it cannot change the world,” she told reporters at a forum in the Grand Palais.

READ: Midway through climate talks, rich-poor divide reemerges

Dahan has been following the COPs of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change since the first in 1995. She also coauthored “Governing the climate? 20 years of international negotiations.”

“I don’t think [Paris] will be a dead end,” she said, meaning a consensus on the agreement was definitely possible, but added that the agreement’s contents will not be as ambitious or as strict on carbon emissions as it would need to be to save the world from the worst consequences of climate change.

“When you have a consensus with 195 countries, what is common is very low, very soft. [Consensus] cannot be enough,” she said. The 195 countries plus the European Union are the parties involved in the negotiations.

But Dahan clarified that COP21 would not fail in the same way as the Copenhagen talks did in 2009. “I’m not here to say that all is bad. That’s not the point,” she said. “The climate question cannot be managed if we don’t understand that there [are] political conflicts, political interests and stakes that oppose [the agreement].”

LOOKBACK: Climate talks in Copenhagen in epic fail

For COP21 in particular, she named India and China as rapidly developing, powerhouse countries who would block the signing of an ambitious legally binding agreement in the interest of their economies.

“Countries like India and China don’t want to sign something too constraining or too ambitious for 20 or 40 years further, and they don’t know what will be the economic landscape, the competition,” she said.

Concrete methods for developing countries to shift to renewable energy, as well as the need for developed countries to help finance such endeavors, also have yet to be addressed, Dahan said.

“That cannot be solved in one conference,” she added.

RELATED STORY

PINAS TO PARIS: An Inquirer Group special report