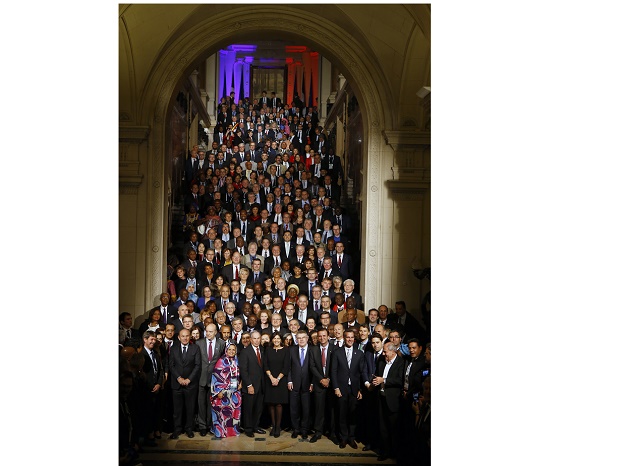

Anne Hidalgo , Mayor of Paris, center, poses for a group picture with Michael R. Bloomberg U.N. Secretary General’s Special Envoy for Cities and Climate Change, with mayors from various cities during a meeting with Mayors at Paris city Hall as part of the COP21, United Nations Climate Change Conference, in Paris, Friday, Dec. 4, 2015. AP Photo

LE BOURGET, France—Negotiators from 195 nations will race Saturday to complete a four-year mission by delivering a blueprint to secure humanity from the consequences of rampant emissions of climate-altering greenhouse gases.

READ: Key sticking points in UN climate talks

Despite being riddled with conflicting proposals, the draft to be submitted by lunchtime will form the skeleton of the most complex and consequential global accord ever attempted.

The stakes could hardly be higher.

READ: Paris climate talks by the numbers

Ministers from across the world will descend on Paris Monday to try to transform the draft into a binding agreement that can rein in emissions that trap the Sun’s heat, warming Earth’s surface and oceans.

Scientists warn our planet will become increasingly hostile for mankind as it warms, with rising sea levels that will consume islands and populated coastal areas, as well as catastrophic storms and severe droughts.

However, cutting emissions requires a shift away from burning coal, oil and gas for energy, as well as from the destruction of carbon-storing rainforests—costly exercises that powerful business interests are determined to press on with.

More than 50 personalities committed to combating climate change, from Sean Penn to US billionaire Michael Bloomberg, Chinese internet tycoon Jack Ma, will try to inject dynamism into the talks, gathering for an ‘action day’ at the UN conference site in Le Bourget on the northern outskirts of Paris.

Negotiators seem confident that they can avert a repeat of a similar effort that failed spectacularly in the 2009 edition of the annual UN talks in Copenhagen, which aimed at a post-2012 deal but broke down, riven by a recriminations between rich and poor nations.

Important promise

It was two years after that failure, at Durban in 2011, that nations agreed to try again for a truly universal climate-saving pact.

Rich nations have been reluctant during two decades of UN negotiations to comply with demands from poorer countries that they must pay for the shift to renewable technologies, as well as to cope with climate change.

At stake is hundreds of billions of dollars that would need to start flowing from rich to developing nations from 2020, under the planned Paris pact.

With frustrations at the conference mounting, UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon called on the world’s developed economies to honour the financing pledge they made at the last major climate summit six years ago.

“I have been urging the developed world leaders that this must be delivered,” Ban told reporters at UN headquarters in New York. “This is one very important promise.”

Participants in the Paris conference say negotiations are constructive but too slow, with the scheduled end of the talks on December 11 looming.

But such deadlines are frequently ignored with weary, sleep-deprived negotiators often slogging through the night to get an accord.

“The negotiating status is still very far away from the target of trying to achieve a comprehensive, effective, balanced and legally-binding agreement which is equitable to all parties,” Chinese negotiator Xie Zhenhua told journalists.

That’s the way it goes

Chief US negotiator Todd Stern said attempts to draw up a draft deal acceptable to all sides were advancing, however.

“It’s moving in the right direction,” he said. “There’s an option that we like. There’s an option that we hate. That’s the way it goes.”

Another battleground is how much to try to limit global warming.

The biggest polluting nations, such as the United States and China, want to enshrine a target of 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-Industrial Revolution levels.

Weaker nations most at risk want a much tougher target of 1.5 C, which would require the global economy to transform away from fossil fuels and be fully reliant on renewables by 2050.

Any deal emerging from Paris is likely to fall far short of what is needed to avert 2.0 C warming. The key, analysts say, will be agreement on review every five years to ratchet up nations’ commitments.