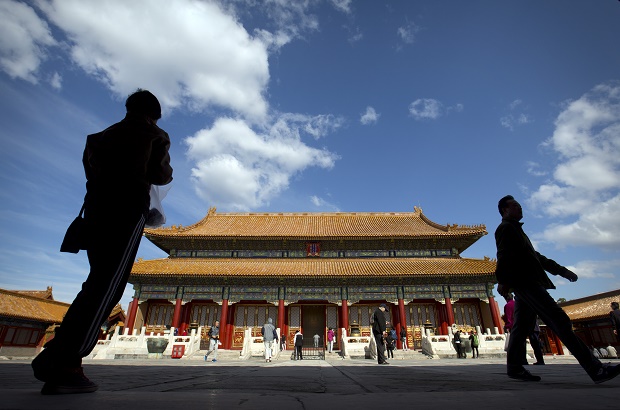

In this Oct. 10, 2015 file photo, visitors walk through the courtyard of the newly-opened Palace of Compassion and Tranquility inside the Forbidden City in Beijing. China’s polluted air is still largely hazardous to health, and officials won’t even guess when air will finally reach levels that could be considered healthy. But some experts, officials and observers see this year’s improvement as the start of a long-term upward trend in air quality resulting from central and local government measures to lower pollution. AP FILE PHOTO

BEIJING — Lawyer Wu Congsi has asthma and keeps air purifiers whirring away in his office, home and car to counter Beijing’s hazardous smog. He prefers to stay inside unless the sky is blue. But this year, he’s been able to regularly walk the 15 minutes or so to work.

That’s because of some good news that so far has gone little noticed outside of China: The air in Beijing — and across the rest of the country — has improved so far this year.

“I just feel generally better in terms of the air quality,” said Wu, 26. “At least so far, this summer and this fall, it’s actually better than last year — just more clear days than previously. I might go out hiking or maybe just stroll around the parks.”

Chinese official sources have cited the improvement, and US Embassy readings have corroborated the findings.

China’s polluted air is still largely hazardous to health — killing 1.4 million people a year, according to one recent study — and officials won’t even guess when air will finally reach levels that could be considered healthy. But some experts, officials and observers see the improvement as the start of a long-term upward trend in air quality resulting from central and local government measures to lower pollution.

READ: Air pollution killing 4,000 in China a day–US study

“It’s not just Beijing or one region,” said Lauri Myllyvirta, who campaigns on air pollution for Greenpeace. “It’s really widespread reductions in (levels of particulate matter and pollutants) across all of eastern and central China.”

Myllyvirta said data on average levels of aerosols, or tiny particles, for the past 15 years from NASA satellites backed up the improvement in official readings.

“The fall from 2014 to 2015 was the biggest in that entire time series — and by a pretty wide margin at that,” he said. “So it’s definitely been a very exceptional year for air quality.”

The early success gives China a credibility boost ahead of a climate change conference beginning late this month in Paris, where countries are to hash out a global agreement intended to slow down global warming. Many are hoping that China, the world’s top emitter of carbon emissions, plays a leading role in the negotiations, particularly as an example to other developing nations.

Yi Bo, an engineer at Beijing Environmental Protection Bureau’s air management office, said the capital had seen a drop in all major pollutants in the first three quarters of this year. That includes a 40 percent decrease in sulfur dioxide and a 19 percent decrease in PM2.5 — small inhalable particles that are extremely hazardous to human health and are considered to be a good gauge of air quality.

“People make an effort and the heavens help,” Yi said, evoking a Chinese idiom to describe what he said were the two reasons for the improvement: government efforts to reduce emissions and more favorable weather conditions compared with last year, including more winds from the north.

China’s pollution problems are notorious after three decades of breakneck growth in which there was little official concern about the environmental impact. The air gets especially bad in the winter when the burning of coal increases and weather patterns add to the smog.

A study led by atmospheric chemist Jos Lelieveld of Germany’s Max Planck Institute and published this year in Nature magazine estimated that 1.4 million people are prematurely dying because of pollution in China each year.

Growing public anger over air pollution has pushed the government to make combating it a priority.

In 2013, months after a particularly bad winter that spurred many Chinese and expatriates to leave Beijing because of health concerns, the central government banned new coal-fired power plants in key industrial regions around Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou, ordered cities to drop their pollutant levels by 2017 and looked increase reliance on non-fossil fuel energy such as wind and solar power. Last year, it changed its environment law to allow unlimited fines against persistent polluters and public oversight of companies’ emissions.

Beijing sits in one of the most heavily polluted regions. Its main sources of pollution are vehicles, coal-burning, industry and dust from construction sites. The city government has been replacing coal-fired boilers with natural gas-powered facilities, raising exhaust emission standards and forcing older, more polluting vehicles off the road. It plans on closing or moving 300 polluting factories this year.

Yi said coal-fired power plants will disappear next year from the capital as its switch to gas power generation is completed, which should both reduce pollution and lessen the city’s greenhouse gases blamed for global warming.

There is a long way to go. Beijing officials say the average PM2.5 figure for the first 10 months of the year was 70 micrograms per cubic meter — down 20 percent from the same period last year. But that’s still double China’s own standard of 35 and seven times higher than an annual mean of 10 that the World Health Organization gives as its guideline.

Daunting challenges also remain elsewhere in China. This week, the northern city of Shenyang had levels of PM2.5 particles that were more than 40 times the safety level set by WHO.

Yi said he expects Beijing to meet the central government-imposed goal of a 25 percent drop in the 2012 level of PM2.5 by 2017. Asked when city residents can expect to breathe clean air, Yi said: “I can only say that the air we breathe will be better and better.”

Tonny Xie, director of the secretariat of the Clean Air Alliance of China, which works with provinces and cities to promote clean air schemes and whose members include Chinese universities and government agencies, said the air quality’s overall trend should keep improving.

That may not mean every year will see improvement, because meteorological conditions also have an effect, Xie said. He also cautioned that if China’s planned economic transformation from heavy industries to a more service-oriented economy does not go as planned, the air quality might “go worse again.”