Saving Kalinga’s dying art of tattooing

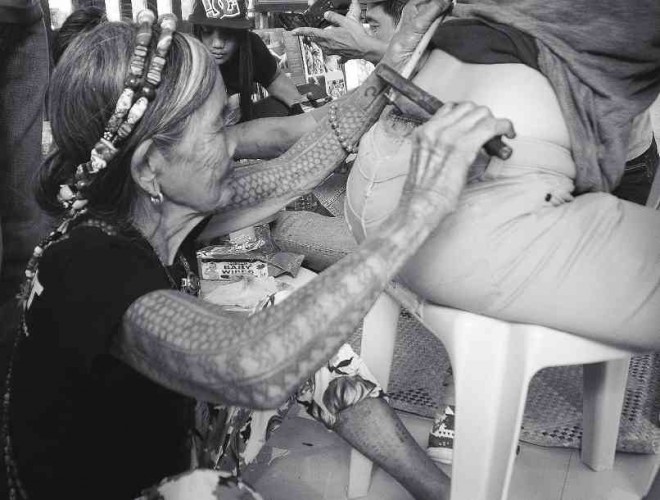

WHANG-OD at work during the Kalinga Foundation Day celebration in February 2014, a rare appearance of the tattoo artist outside of her native village of Buscalan in Tinglayan town. ESTANISLAO ALBANO JR./CONTRIBUTOR

WHANG-OD’S mastery of Kalinga province’s ancient art of tattooing has been featured on the world stage and has made this elderly woman of the Butbut tribe in Tinglayan town a media sensation.

She was featured in a Discovery Channel documentary and was the primary subject of an anthropological book on Kalinga tattooing written by University of the Philippines professor Analyn Salvador-Amores.

Recently, Whang-od has been nominated by online supporters, as well as by Kalinga residents, for recognition as a national cultural icon.

Disappeared

But the traditions that compel Kalinga residents to submit to body inking have all but disappeared, according to Whang-od’s own relatives.

Article continues after this advertisementMiguel Atompa, 66, Whang-od’s third cousin on her father’s side, and Lutheran church pastor Luis Aoas, 67, the artist’s relative from the neighboring Basao tribe, said tattoos have lost their meaning because of modern civilization and religion.

Article continues after this advertisementFirst to go is the “fi-ing,” which refers to the elaborate tattoo that decorates the chest and arms of a tribal warrior, who has killed a skilled enemy during a tribal war.

A warrior who kills in defense of the tribe becomes worthy of that badge of honor, Aoas and Atompa said.

The last time a member of the Butbut tribe received his “fi-ing” was in 1972 following a war with a rival tribe, Atompa said. Citing an account by his father-in-law, Whag-ay, Atompa said Whang-od herself performed the “fi-ing.”

Whag-ay was the tattoo master of the Butbut tribe, who preceded Whang-od.

Skin decorations

“Fi-ing” is all but extinct, Aoas said, because education, religion and the government helped discourage Kalinga villagers from pursuing tribal vendetta. Tribal laws are also gradually being changed by the continuing peacemaking efforts among Kalinga communities, he said.

Features of the “fi-ing” have evolved and are imprinted as skin decorations for tattoo enthusiasts, occasionally as images of an eagle or a snake. The tattoos are also placed in parts of the body that could be concealed by clothing.

Women have also started to wear conventional attire, the second factor, which gradually eroded the cultural rationalizations for ancient tattooing in Kalinga.

Women were adorned with tattoos called “fatok,” which manifested beauty and wealth. Tattooing an arm would cost the family of a woman a piglet as payment, or a “dalan” of havested rice. A “dalan” is equivalent to 10 “iting” (a bundle of manually harvested rice that is the size of an average person’s wrist).

Aoas said his mother, Ana, used to go topless when undertaking strenuous work, so women of her time often displayed their tattoos.

But Kalinga women who were schooled shunned the tattoos in the 1960s, he said.

That did not stop the traditional tattoo artist from earning a living.

In their prime, Whag-ay and Gannisi, the tattoo master from the Tinglayan tribe, could buy three full-grown hogs, after a month’s work imprinting the “fatok” and “fi-ing,” Aoas said. A grown pig today would be worth P8,000.

With a steady stream of visitors, Whang-od is said to earn at least P5,000 a day, her relatives said.

Atompa said Whang-od used to make a living from the rice paddies she inherited from her parents. In Butbut culture, the firstborn inherits the family property, he said. Whang-od is the eldest of eight siblings.

But her career as a traditional tattoo artist zoomed when she was featured by Discovery Channel in 2009, Atompa said. One of Whang-od’s memories involved her grandfather’s skills, which she mastered by experimenting on her foot, he said.

In September, a petition nominating Whang-od as a national artist began circulating over social media. Edward Laurence Opena, a Cebu City biology instructor, initiated the online campaign, convinced that granting Whang-od the recognition could hasten efforts to save the dying art.

Ahead of the online campaign, the provincial board of Kalinga passed a resolution nominating Whang-od for the National Living Treasures Award.

The resolution said recognizing Whang-od’s skills could ensure the transfer of the traditional tattoo art to the next generation “with the same degree of technical and artistic competence.”

The resolution’s sponsor, Board Member Alonzo Saclag Jr., said the award would allow Whang-od to pursue authentic Kalinga tattoo art. He said the elder is sometimes forced to deviate from her art to accommodate the wishes of her younger clients.

Under Republic Act No. 7355 (Manlilikha ng Bayan Act), a national living treasure is eligible for an initial grant of P100,000, a lifetime monthly allowance of P14,000, and medical and hospitalization benefits of up to P750,000.