Saving Lucena City’s heritage icons

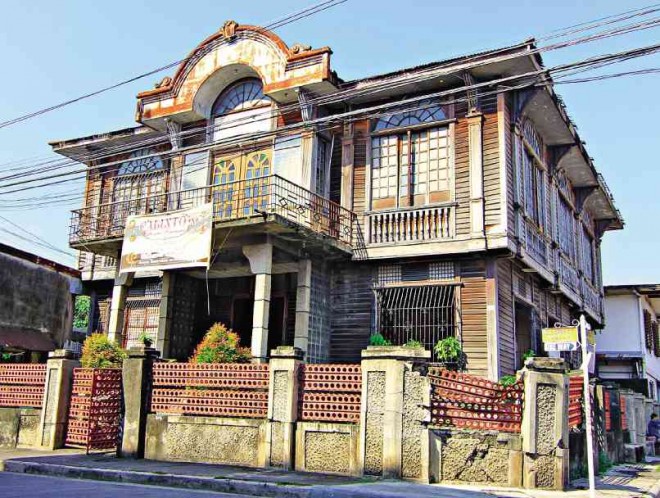

THE ZABALLERO mansion along Allarey and Zamora Streets in Lucena City was built during the boom of the copra period in early 1900s. DELFIN T. MALLARI JR.

With the 77-year-old iconic, stonewalled Philippine National Railway (PNR) station in Lucena City gone in a controversial way, the once lethargic public concern over the fate of other heritage sites and structures in the capital city of Quezon province has awakened.

“We’re now going to conduct an inventory of all remaining heritage buildings and places in the city with the aim of protecting and preserving them for future generations,” said Councilor Sunshine Abcede-Llaga.

The city government is waiting for guidance from the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) on how to proceed with the identification of historical public and private buildings. This will be done in collaboration with different local government offices and the private sector, according to Arween Flores, chair of Lucena Council for Culture and the Arts (LCCA).

One of the primary goals is for the National Historical Commission of the Philippines (NHCP) to mark the old City Hall building at the city center a historical site. Flores said an NHCP-marked heritage structure was protected by Republic Act No. 10066, or the National Cultural Heritage Act of 2009.

The building was put up in 1910. In front of it is the concrete monument of national hero Dr. Jose Rizal that was erected in 1927.

Article continues after this advertisementCarlos Villariba, a local historian and a consultant of the provincial government, hailed the heritage structures inventory project, saying it would strengthen the ties of the present generation to the rich and colorful past of Lucena.

Article continues after this advertisement

Race against time

“But its success is a race against time,” said Villariba, a passionate collector of rare historical photos of the city and other parts of the province. Most remaining old structures are in varying states of deterioration and are poorly maintained by their owners.

Under Section 5 of RA 10066, structures age 50 years or more should be considered important cultural property (ICP) and protected from exploitation, modification or demolition. But the law has been rarely observed and most often ignored by the owners, even by concerned government agencies.

“Most of the antique buildings and residential houses in the city are now being demolished for financial consideration. Some are being rented out to become business establishments,” Villariba said.

In January 2014, Lucena lost its most iconic heritage structure—the Villa Perez mansion along Quezon Avenue built in 1907—when it was demolished to clear the way for the six-story Systems Technology Institute (STI) school building.

Villariba named the Zaballero mansion on Allarey and Zamora Streets and the Daleon ancestral house along Merchan Street some of the old residential houses built during the American period.

The stately facade of the Zaballero mansion has been preserved but it has been converted into a coffee shop. On the other hand, the imposing concrete Daleon house is still being occupied by clan members.

Like the rows of grandiose heritage mansions in the nearby town of Sariaya, Villariba said, most of the old palatial houses in the city were built during the boom of the coconut industry in early 1900. “The owners … were scions of rich coconut hacienderos,” he said.

The destruction of the PNR station building, considered a local heritage icon, triggered the rebirth of local heritage protection advocacy as city officials, concerned residents and even the younger generation raised howls of protest.

In a letter to Mayor Roderick Alcala, the city council led by Vice Mayor Philip Castillo asked that such a historical landmark not be torn down and that all works and measures of conservation should be undertaken only upon prior approval of the NCCA.

Any work must strictly adhere to the accepted international standards of conservation, Castillo said.

In a letter dated Sept. 7, four Grade 5 students of International School for Better Beginnings—Adriana Ysabela Nieto, Lharz Gilbert Dapla, Christian Alcala and Juliana Tuazon—also appealed to Mayor Alcala to stop the project.

“We couldn’t help but be saddened knowing that the city is losing a heritage again. Young as we may be, we are very proud of our history and roots that make up our identity,” they said in the letter. A photo of it was posted on the Facebook page of Nieto’s father, Vladimir, who is also a known local heritage protection advocate.

The students said the PNR station “is something that makes us remember who we are as Lucenahins.”

Early last month, Alcala ordered the PNR to stop the “restoration” of its station for lack of city permits. He directed its engineers to bring back the destroyed parts of the building to its original form.

The first PNR station in the city was made of wood materials in 1913. It was rebuilt in 1938 and made with concrete. Stone walls were put up, based on a design of national artist Juan Arellano, when the first Bicol-bound train was put into operation.

The destruction of the train terminal could have been avoided if only the city government adopted the proposed legislative measures by one of its councilors in 2013. In November 2013, a resolution was filed by Councilor Rey Oliver Alejandrino, calling for an inventory and identification of the city’s remaining heritage structures for preservation and protection, but it was not acted upon by the concerned committee and has since been archived.

Historical gems

Villariba urged the owners of antique houses to cooperate with the city government project to preserve and protect their property. “They are all gems in the city’s rich cultural history. Once they are demolished, altered beyond recognition of their colorful past, they’re gone forever,” he said.

Gov. David Suarez has aired a similar appeal to the owners, noting the structures’ significance to the rich cultural legacy of Quezon. He said one of the thrusts of his administration is to protect, restore and rehabilitate the long-forgotten historical treasures, starting with the capitol building, which is also an Arellano masterpiece.

“If the provincial government can be of help, we will readily provide assistance. They just have to let us know of their intention,” Suarez said.