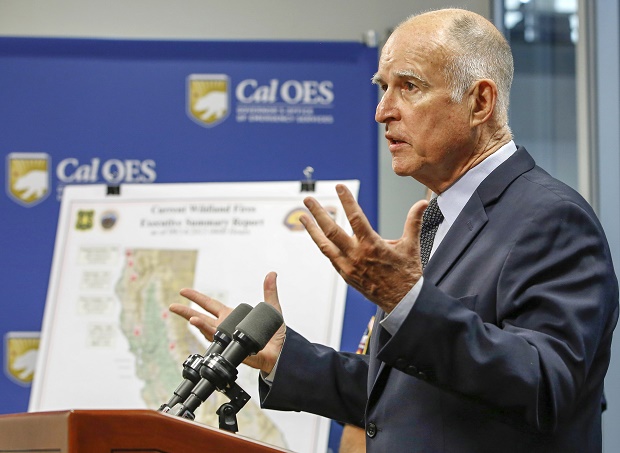

In this Sept. 14, 2015, file photo, California Gov. Jerry Brown discuss the state’s wildfire situation at the Governor’s Office of Emergency Services news conference in Rancho Cordova, California Gov. Brown signed legislation, Monday, Oct. 5, 2015, allowing terminally ill people in the nation’s most populous state to take their lives, saying the emotionally charged bill forced him to consider “what I would want in the face of my own death.” Brown, a lifelong Catholic and former Jesuit seminarian, said he acted after discussing the issue with many people, including a Catholic bishop and two of his doctors. AP FILE PHOTO

SAN DIEGO — It will soon be legal for the terminally ill to end their own lives in the nation’s most populous state, and right-to-die advocates expect other states to follow California’s example.

Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill Monday that allows such physician-assisted deaths, marking a major victory for proponents who spent decades and millions of dollars pushing through such a measure.

California marks a turning point, and its legislation includes more safeguards than the other four states where the practice is legal, the law’s supporters say. They are now focusing on New Jersey, where the state Senate is slated to debate a similar bill this fall, and Massachusetts, where a legislative hearing on the issue is set for this month.

READ: California lawmakers approve right-to-die legislation

“My phone has been ringing off the hook with people who now want to bring forth bills,” said Jessica Grennan at Compassion and Choices, a national advocacy group leading the fight. “I think what happened in California is definitely going to inspire people across the country to honor these options at the end of life.”

But opponents say the fight is not over in California and they will be beefing up their efforts elsewhere. One group filed paperwork Tuesday with the California Attorney General’s Office to launch its drive for a referendum to overturn the law.

Legislation introduced this year in other states stalled, but legal experts say California has proven to be a trendsetter. Doctors in Oregon, Washington state, Vermont and Montana already can prescribe life-ending drugs.

“A significant part of the country now has a right to physician-assisted death,” said Erwin Chemerinsky, a constitutional law professor at the University of California, Irvine. “I think this reflects growing public support for a right to death with dignity.”

The Catholic Church and advocates for people with disabilities say measures like California’s legalize premature suicide and put terminally ill patients at risk for coerced death.

“The impact of what happened in California may be a lot more limited than some people think because other states really have paid a lot more attention to the objections and concerns of the disability community,” said Marilyn Gold, a senior policy analyst with the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund.

Those voices were drowned out in California by assisted-suicide supporters who spent millions on their campaign, Gold said. But she doesn’t expect that to happen elsewhere.

“In state after state after state, there have been multiple attempts, and these measures have failed,” Gold said.

READ: Right to die: Colombian man ends life with government backup | Right-to-die group fined $30K in US woman’s suicide

Gov. Brown, a lifelong Catholic and former Jesuit seminarian, said he consulted a Catholic bishop, two of his own doctors and friends “who take varied, contradictory and nuanced positions.”

“In the end, I was left to reflect on what I would want in the face of my own death,” wrote the Democratic governor, who has been treated for prostate cancer and melanoma. “I do not know what I would do if I were dying in prolonged and excruciating pain. I am certain, however, that it would be a comfort to be able to consider the options afforded by this bill.”

Proponents credit support for the law by both parties to Brittany Maynard, a 29-year-old California woman with brain cancer who drew national attention for her decision to move to Oregon to legally end her life.

They say Maynard touched people personally, which helped cross political and religious divides.

In a video recorded days before she took life-ending drugs, Maynard told California lawmakers that the terminally ill should not have to “leave their home and community for peace of mind, to escape suffering and to plan for a gentle death.”

Maynard’s husband and mother testified at legislative hearings and met with undecided lawmakers. They are expected to travel to other state capitols in coming months to do the same.

The California measure applies only to mentally sound people and not those who are depressed or impaired. The bill includes requirements that patients be physically capable of taking the medication themselves, that two doctors approve it, that the patients submit several written requests and that there be two witnesses, one of whom is not a family member.

The law cannot take effect until the session formally ends, which is not expected until 2016.

A group called Seniors Against Suicide filed paperwork with the Attorney General’s Office on Tuesday asking that the issue be placed on the ballot in November 2016.

To qualify for a referendum, they must collect more than 365,000 signatures.