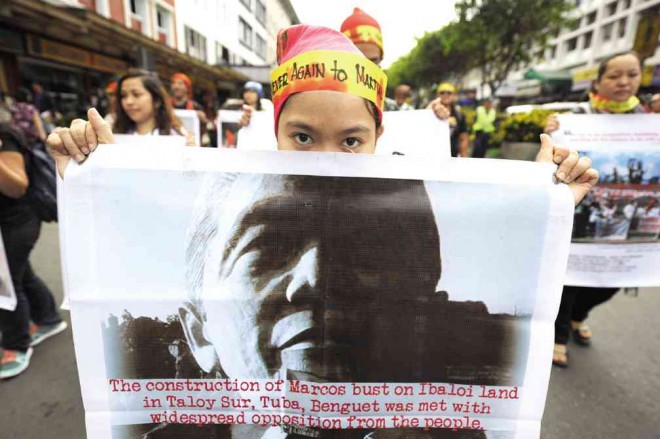

MARTIAL LAW REVISITED Around 50 activists marched in downtown Baguio on Monday to revisit the atrocities committed during martial law. Since the ouster of the late strongman Ferdinand Marcos, the monuments to his rule, including a giant bust along Marcos Highway, have been destroyed. EV ESPIRITU/INQUIRER NORTHERN LUZON

Books and journals are being published, movies made, plays and art exhibits mounted to record the ordeal of the Filipinos under martial law and the disgrace of the New Society (Bagong Lipunan), so that people will keep remembering.

Those in the know find that period in our contemporary history repugnant. What disturb them is the twisting of history among the new generation, the so-called millennials who weren’t even born during those interesting times.

To many of these innocent young, Marcos was a hero and the martial law years were the halcyon days of the republic. We don’t know how they’ve come to think so—or, have they been deliberately misled?

How then should we remember Ferdinand Marcos? How do we identify the legend, the bias and the truth?

This was the core of historian and Inquirer columnist Ambeth Ocampo’s lecture at the Ayala Museum in Makati City on Sept. 26.

Ocampo has a way of turning history into something mundane and of the moment. In this, the second in his series of four lectures billed as “History Comes Alive!” nothing could have prepared the audience for dry academic stuff to give one the giggles.

Over 600 people thronged the place, filling the museum lobby to standing room capacity, to hear about one of the most polarizing periods in Philippine history: the Marcos years.

“I didn’t expect this,” Ocampo said. “I thought only a few would come. I’ve been doing Jose Rizal for 20 years but Marcos is not really in my comfort zone. Marcos is more complicated than Rizal—because he did many, many bad things. Rizal did only a few bad things.”

Ocampo introduced the lecture proper by expounding on point of view. This he illustrated by critiquing the historical perspective taken by the filmmaker of “Heneral Luna” (Ocampo’s mentor Teodoro Agoncillo argued Luna did not fight the Spaniards or win a single battle, and he was a traitor to the 1896 Revolution); and by showing the Disney cartoon short, “The Three Little Pigs,” followed by the Big Bad Wolf’s apologia in a spoof newspaper account.

“All stories have a point of view,” Ocampo said. And with that, he launched on the Marcos years.

What concerned him as much as history is historiography, or the study of the ways history is being written.

Sniggers, laughter

To sift fact from fiction, Ocampo raised several questions: Do newspapers provide us with all the news of the day? Do they provide objective or biased news? What about tabloids?

What do vintage newspapers say about the past, or in relation to our time? How do we tease out truth from a biased source?

His answers, with accompanying visual illustrations, were met with sniggers and laughter from an audience that could not have enough of mockery of the decadence, brutality and folly of the Marcos years.

The most rollicking laughter was reserved for his account of a dinner with Imelda Marcos, an encounter that lasted from 6 p.m. to 3 a.m.—as she treated him to stories of life with her late husband and video screening of her sojourn in Persepolis, rubbing elbows with Farah Diba, sniping at the fashion sense of Queen Elizabeth, hand-kissing with Mao Zedong, and encharming Moammar Gadhafi and Fidel Castro—all the while flashing a big yellow diamond on her dainty finger.

Mythmaking accounts

One approach to history that Ocampo suggested was by examining not only the newspaper headlines of that era and the mythmaking books Marcos was supposed to have written but also the equally mythmaking movies—“Iginuhit ng Tadhana,” “Pinagbuklod ng Langit” and the unfinished “Maharlika” (starring the famous Dovie Beams).

Ocampo debunked the illusion of discipline, peace and order during the martial law years, explaining that bad news was then suppressed, freedom of expression repressed, as all were Marcos newspapers, and no headline would dare rock the boat—so there reigned that calm before the storm.

As to Marcos’ acquittal of the 1935 murder of his father Mariano’s political rival, Julio Nalundasan, Ocampo pointed out that Jose P. Laurel, who wrote the decision reversing the conviction, had experienced a similar predicament in his youth. That was why the Laurels were virtually untouchable during the Marcos era, Ocampo concluded.

What was the situation that made Marcos possible? Improbably, Ocampo pointed to the Vietnam War. The United States needed Marcos at that time for the military bases, so it coddled him and garlanded him with one war medal after another.

There were three war medals recorded in a 1945 photograph of him in uniform. The number ballooned to as many as 32 since the mid-1960s. This was exposed during the 1986 snap election.

Ocampo conjectured that since father Mariano was executed by guerillas as a collaborator, son Ferdinand must have wanted so much to project himself as a larger-than-life war hero.

Remembering, forgetting

“To demonize Marcos is easy,” Ocampo said. “Putting him in context is difficult.”

He revealed he got a copy of the so-called “Marcos Diaries,” a daily record of Marcos’ term in office as President which he started on Jan. 1, 1970. Another mythmaking account, Ocampo found out.

After the ouster of the Marcoses from Malacañang, some 600,000 pages of documents were said to have been retrieved. These have been digitized, but Ocampo estimated it would take 10 years for historians and scholars to put them in order.

“History is about remembering; it is also about forgetting,” Ocampo said toward the end of his talk. “When I started as a historian, I was always pessimistic … History is the resolve that makes us act so things don’t have to be the way they are. History is about hope, not despair.”

Students and society figures, the culturati and walk-in folk, young and old alike, came to hear the lecture. If there’s something not to despair about, this is it. It bodes well for the youth that they want to learn more about the pre-Edsa era.

“Maybe I could do Marcos for another 20 years,” Ocampo said.

RELATED STORIES

Palace cites need to impart martial law lessons to youth

Sa kabataang di nakatikim ng Martial Law, ito ang ginawa ni Marcos