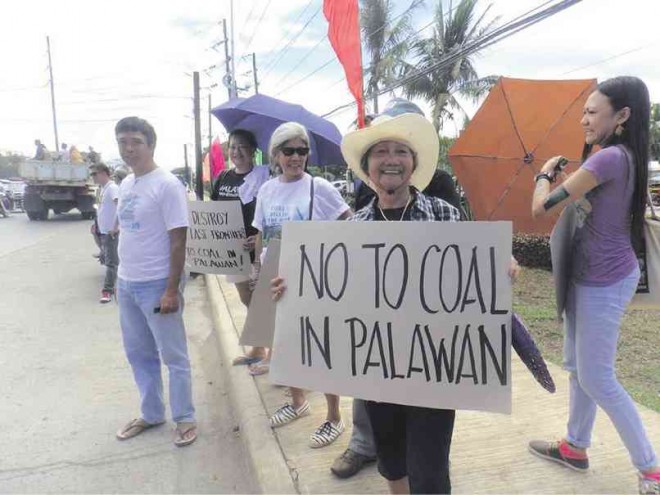

ENVIRONMENTALISTS protest the planned construction of a coal-fired facility in Palawan province.

NO TO COAL CAMPAIGN/CONTRIBUTOR

Environmental groups in Palawan province are celebrating. The signing of a power supply agreement between Langogan Power Corp. (LPC) and Palawan Electric Cooperative (Paleco) last week has been hailed as a milestone in Palawan’s socially charged quest for reliable power supply.

Paleco finally gave LPC, the fledgling renewable energy (RE) company, a 20-megawatt deal after years of trying to get a contract to generate electricity from three major river systems in the mainland. The decision drew praises from consumers and environmentalists lobbying for a stop to the planned construction of a coal-fired facility by the Consunji-led DMCI Power Corp.

“This is a win for consumers and the people of Palawan. Renewable energy is the way to go,” says Cynthia Sumagaysay-del Rosario, a lead campaigner of Palawan’s No To Coal Movement.

LPC joined two other diesel and bunker oil-based independent companies as suppliers of Paleco, along with DMCI, as the province anticipates a leap in power demand due to an expected surge of investments in tourism and agro-industrial projects.

Energy policy clash

The proposed coal plant, an oxymoron considering the many factors why Palawan is tagged the country’s last environmental frontier, has pitted conservation nongovernment organizations (NGOs) and local communities against the provincial government in a heated, often emotional, policy clash.

The local government firmly believes that Palawan has to embrace coal for lack of a better choice to meet its growing demand for electricity. At least, that has been Gov. Jose Alvarez’s known stand on the issue. His strong personality and leadership style have petrified the entire government bureaucracy into adopting this position without question.

When DMCI faced angry residents and officials of Western Philippine University (WPU) in Aborlan town, its first choice of a plant site, Capitol’s political machinery was mobilized to support the Consunji firm. It was not enough to stop the rallies and protests.

The debate sparked an intense policy conflict between the local government and civil society, which came to a head when Alvarez angrily withdrew support from WPU and canceled the scholarship of some 2,000 students for simply signing an anticoal petition.

Paleco has also become a battle arena for coal. Recent elections in the board of directors of the cooperative were marred by allegations of manipulation by Capitol as it vied to gain control over the private group’s policymaking body.

Runaround

For the longest time until the signing of the Langogan power contract, Paleco has been giving LPC the runaround as Capitol tried to portray the group as lacking in financial capacity. In the end, the Paleco board decided that LPC, an RE company certified by the Department of Energy, has the capacity to just do the job.

The Manila-based LPC, on its website, describes itself as “a small British, North American and Filipino group of energy development professionals who all live in the Philippines and who have partnered with a major European national electricity utility and a large national Asian energy company.

They have 60 years of combined experience in energy project development in remote locations, with in-depth hydrology and engineering expertise, and in-depth knowledge of the Philippines’ energy sector, 10 years of energy project investment appraisal; and 12 years of energy project work with NGOs.

Mike Wooten, the British manager of LPC, told the Inquirer following the contract signing that the company would begin work on access roads to prospective river sources in the next two weeks, starting with Batang-Batang River in Narra. Plant construction is expected by January 2016.

Anticoal campaigners are hoping the LPC contract to augment supply to the grid will convince the provincial government and Paleco to set aside altogether the DMCI coal plant despite the company having signed already its own separate contract two years ago.

Permanent source

“There is enough time for Palawan to go renewable as its permanent source of power. We hope the provincial government will realize this, and adopt a new policy approach toward renewable energy. The provincial energy development master plan even prescribes it,” says environmental lawyer Jansen Jontilla of the Environmental Legal Assistance Center.

LPC’s contract has taken the wind off the sails of the coal plant project which, even with a strong push from the provincial government and most local officials, continues to face civil society opposition and legal challenges. Since signing its own contract to supply 25 MW to Paleco two years ago, DMCI has not delivered on what it is legally bound to deliver.

Paleco has faced increasing pressure from consumers to junk DMCI for breach of contract. In fact, it did issue a notice of default in June which the company simply brushed aside.

Public pressure against the DMCI plant has built up since the Palawan Council for Sustainable Development granted last month a Strategic Environmental Plan clearance to the project amid protests from civil society and even from Tourism Secretary Ramon Jimenez, who sent a memorandum to President Aquino seeking Palace intervention to stop the project.

LPC has now been given the stage to prove that RE technology can work in Palawan, but its road to success isn’t necessarily easy. While the technology of run-of-the-river power generation looks fairly solid, experts have continuously doubted its ability to perform during dry seasons when the rivers dry up.

Favored status

Because of its favored status as an RE company, LPC enjoys being first dispatch in the Paleco grid. This means that whatever power it generates is immediately used as base load, as well as increased pressure on the company not to leave the end users in the dark.

LPC’s mini-hydro project shifts the continuing debate on coal in Palawan in many respects. It already debunked the claim that no RE company is interested in Palawan; hence, the only option is coal. Already, Paleco is reportedly entertaining unsolicited proposals from other RE firms interested in its northern Palawan’s franchise area.

LPC’s success is considered a game changer in this debate and could force DMCI to adopt or be steamrolled over as it faces the prospect of redundancy and a string of legal compliance issues.

Even a 6-MW initial addition that it will deliver from its first planned series of three plants along the riverbanks should stabilize the supply enough for Paleco and provincial policymakers to shift to strategic thinking on how to deal with energy challenges.

To begin with, Palawan’s energy master plan—a result of a long-term vision and a healthy dose of expert inputs—has already adjudged coal expensive and inefficient. What keeps DMCI ticking though is its adamant stance to hold on to its contract and the accommodation it enjoys from the local government.