(Last of a series)

A doctor, a businessman and an award-winning poet were brutally killed before they turned 30 during the dark years of Ferdinand Marcos’ martial law regime.

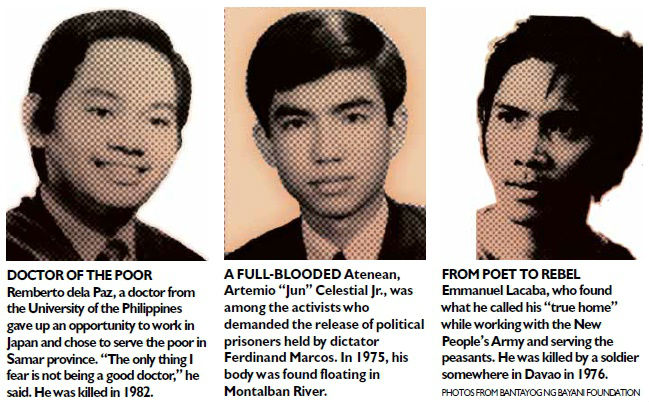

Remberto “Bobby” dela Paz, Artemio “Jun” Celestial Jr. and Emmanuel “Eman” Lacaba were among the best and the brightest who could have been the country’s future leaders.

Theirs are among the 253 names etched on the black granite Wall of Remembrance of Bantayog ng mga Bayani Foundation in Quezon City—so honored for being the country’s modern-day martyrs and heroes.

They gave up their lives fighting the Marcos dictatorship.

Bobby was a medical doctor who graduated from the University of the Philippines (UP) College of Medicine. But he chose not to work abroad. Instead, he set up his practice among the poor people in Samar province.

Bobby was working in his clinic in Catbalogan City when he was shot by a lone gunman in April 1982.

Body on a river

Jun was a true-blue Atenean and was the secretary general of the student council. After working at the National Grains Authority, he put up a tailoring business with a friend.

In February 1975, Jun wrote a letter to Marcos demanding that the latter free all political prisoners.

Three days later, his body was found floating in the Montalban River near Wawa Dam. His skull was broken and his body was mangled.

Mass grave

Eman was an honor student from grade school to high school and won a full scholarship at Ateneo de Manila University. He was an award-winning poet, a UP lecturer, a fictionist, an essayist, a playwright and a magazine illustrator, among his many talents.

How Eman died is told in the book, “Six Young Filipino Martyrs.” His killer, as ordered by a sergeant of the Philippine Constabulary (now the Philippine National Police), “put a gun in Eman’s mouth and pulled the trigger, sending the bullet crashing through the back of his skull. As he fell, a second bullet was fired into his chest.”

The killer and other soldiers then tied a rope around Eman’s body and dragged it like a cow along a craggy road in Balaag, Tucaan, in the Davao area and buried it in a shallow mass grave.

Tribute from Cory

Speaking in November 1989 before the mothers, wives and relatives of the heroes honored at Bantayog ng mga Bayani, then President Corazon Aquino said: “Many of those whose names are carved on the wall of this monument were, once upon a time, considered by the State as insurgents—its enemies, who were menaces to society.

“This was why many of them were arrested, kidnapped, tortured, salvaged or killed in action by the martial law forces.

“In truth, they were freedom fighters who fought and died on the side of the people. No other distinction is needed. ”

She added: “By their death, they taught us how to live—with full commitment to the cause, with the courage of our convictions, with the strength to persevere and with the firm belief that no effort ever really goes to waste, no loss is irretrievable. ”

Dr. Bobby dela Paz

Bobby did his required six-month rural medical work in Samar where he saw the impact of Marcos’ one-man rule on the lives of the ordinary people.

In the book “Six Young Filipino Martyrs,” his wife, Sylvia, also a doctor who also chose to work in Samar, gave examples of what the couple saw.

“When we got to Samar,” she said, “we saw the stark reality of people living on one meal a day, composed of seashells and root crops; farmers deprived of their lands to make way for multinational interests on mines; fishermen deprived of the chance to catch fish because of multinational crawlers.”

After Bobby became a full-fledged doctor, he had the opportunity to go to Japan to take up bio-medical engineering. But he opted to set up medical practice with his wife as community doctors in Gandara, Samar.

Well-loved doctor

Their clinic was open to everyone, especially the poor. Bobby went to far-flung areas to attend to the sick, taught first-aid treatment, proper hygiene and nutrition to the barrio folk.

This invited suspicion that he was a sympathizer or a member of the New People’s Army (NPA).

With threats on the couple’s safety becoming more and more apparent, friends urged them to leave, but they only moved to Catbalogan City to continue their practice.

Bobby had said: “I am a doctor and the only thing I should fear is not being a good one.”

And he was a well-loved doctor.

When news spread that he was shot, people from all walks of life rushed to the hospital where was taken. At least 200 people immediately gathered and offered their blood and money to save his life.

Residents of Gandara came to keep vigil and the folks of Zumarraga, where Bobby first served, were said to have cursed the waters that would not allow them to cross to Catbalogan.

They, too, wanted to give their doctor their blood.

Bobby’s death was a big blow to the cause of Philippine rural medicine—he was the first doctor to practice in the rural areas to be brutally gunned down.

Artemio Celestial Jr.

Jun became active with the Student Catholic Action (SCA) and joined student fora and marches across the Ateneo campus, calling on other students to become involved.

He became the student council’s secretary general in November 1971 after leading council officers were expelled for their activism.

According to the biography notes by the Bantayog Foundation, Jun himself was expelled along with other activists when martial law was declared, their pictures posted in the school’s guardhouses.

Jun and his younger brother Joel, also an activist, escaped when soldiers raided a home in Project 4 in Quezon City.

Jun was a full-blooded Atenean, according to a list of dead Ateneans posted by Ateneo’s Alumni Office. He finished grade school in 1965, high school in 1969 and graduated with an AB Economics degree in 1973.

Honors from Ateneo

In November 2005, Ateneo honored Jun with three other Ateneans—Ferdinand Arceo, William Begg and Lazaro “Lazzie” Silvar Jr.—as Ateneo’s very own heroes for joining the movement against the dictator Marcos and dying at the hands of state forces.

Jun was once arrested and kept in prison for a few days when he was mistaken for his brother Joel, who had joined the underground. Upon release, Jun continued to help the underground movement with financial and logistical support.

Joel himself was arrested in 1973 and detained in Fort Bonifacio, where many of Jun’s friends were also imprisoned.

In February 1975, three days after he handed a letter urging Marcos to free political prisoners to a “person of authority” who then gave it to a soldier, his mangled body was found floating in the Montalban River.

Emmanuel Lacaba

Eman was the editor of their high school paper and later received an American Field Service (AFS) scholarship. He completed his fourth year at Robert Millikan High School in Long Beach, California, where his poem, “Golden Gate Bridge,” won the overall poetry first prize.

Upon graduation, the bemedaled Eman had his pick of scholarships from UP, De La Salle University and Ateneo. He chose a scholarship at Ateneo, where he graduated in 1970.

Eman was arrested and detained for his participation in a strike. Because of this, he lost his job at UP where he was teaching Rizal’s life and works.

Shy poet to a warrior

In 1974, Eman decided to join the NPA in South Cotabato province. He took up the name Popoy Dakuykoy, an allusion to a comic book character whose name he had once used for a character in an epic poem he had written in the 1960s.

His radicalization from a scholar and “a shy young poet forever writing last poem after last poem” to “a people’s warrior” can be discerned from the various poems he had written.

His earlier poems touched on his search for meaning and his efforts to find himself. From Mindanao, he wrote a friend: “I think I belong here. I feel no sadness anymore; I only remember . . . the world we left behind, whose wiles of momentary farce and luxurious living we have to continue to struggle against.”

True home found

Two months before he died, his poem states: “The road less traveled by we’ve taken—And that has made the difference. . . Here among workers and peasants our lost generation has found its true, its only home.”

Eman had been with the NPA two years when he met his death in March 1976.—Minerva Generalao, Chief, Inquirer Research

Source: Inquirer Archives, Bantayog.org, Bantayog Foundation Research and Documentation, Six Young Filipino Martyrs edited by Asuncion David Maramba

RELATED STORIES

And many disappeared in the prime of youth