MEET Gabbriel Garcia, 19, of Pangasinan and Joanna Rubi, 18, of Cebu. They are Filipinos studying in New Zealand, the stunningly beautiful country way, way down under that indigenous Maoris first named Aotearoa, meaning “Land of the Long White Cloud.”

Movies such as “The Lord of the Rings,” “The Hobbit,” “The Chronicles of Narnia” and “The Last Samurai” are a good visual introduction to New Zealand, but an actual visit makes you realize that the place has much, much more to offer than just eye candy in feature films, travelogues and tour blogs.

Education, for one. New Zealand attracts international students with its excellent, globally ranked education in numbers that translate to $2.85 billion in revenues. This is why international education is on its national agenda for businesses to grow.

To showcase its scholastic offerings and to mark the 40th anniversary of its membership in the Association of South East Asian Nations (Asean), the government, through Education New Zealand (ENZ), invited journalists from Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines—this writer included—on a five-day tour of its universities, polytechnic institutes, colleges of English and secondary schools.

And that was how we met Garcia and Rubi.

Garcia is a Cookery student at Christchurch Polytechnic Institute of Technology (CPIT). That he wants to work in the kitchen is in keeping with the labor market trend toward restaurant management and food service.

Rubi is a Computer Science student on a scholarship in the Faculty of Science at Victoria University of Wellington (Victoria). That she headed for the computer lab is good news for those who have been trying to push more women into STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) courses.

Pinoy finds recipe for food career

GABBRIEL Garcia was midway in his first year of high school when the family left the Philippines. He had to repeat the grade in New Zealand.

Prior to 2006, the Philippines did not appear in the NZ Census of top 10 nationalities of immigrants. But by 2013, Filipinos had become the fourth largest immigrant community, after India, China and the United Kingdom.

By 2014, according to the New Zealand Herald, immigrants from the Pearl of the Orient had more than doubled to 40,000. Among the Asean nations, in fact, Filipinos are the biggest migrant community in New Zealand today.

Many of the Filipinos are construction workers who have been imported to help in the rebuilding of Christchurch, the South Island city devastated by a 6.3-magnitude earthquake in 2011. Other Pinoys have been hired by the dairy farms. In Christchurch, Filipinos are also known for running care homes for the aged.

Not interested in construction or dairy work, Garcia enrolled in the one-year Certificate in Cookery program at CPIT.

“I’m interested in food,” he said, adding he wanted to develop the skills he would need to get a job as a restaurant chef.

If he wants to advance his skills, Garcia can stay on at CPIT for another year and earn his Diploma in Cookery.

And that is the beauty of postsecondary education in New Zealand—in most cases, it is “ladderized” or by levels that are pathways to higher education. A student can enroll in a program and earn a certificate after one year, a diploma after two years, a bachelor’s degree after three or four years, depending on the subject area.

By contrast, the standard education after high school is a four-year drudgery in the Philippines. If you leave school after freshman year, you leave empty-handed, and you become just another college dropout.

Garcia said he picked CPIT because the students there “get to work with an experienced and award-winning staff who excel in their professions.” The facilities were also an attraction for him. “We work in kitchens with good quality commercial equipment and teaching resources,” he said.

Vocational institutes like CPIT offer hands-on training and practical education to students who want to be work-ready for the specific industry they are eyeing.

CPIT School of Food and Hospitality offers the cookery and chef training program (cookery, career baker, advanced cookery, advanced patisserie) and the hospitality program (food and beverage service, travel operations, hospitality management).

In addition to its five commercial-grade kitchens, it has a bakery, a fully licensed wine bar and a six-station barista room on campus for skills training. Before going out to the industry, the students get work experience in The Pantry café and the Visions on Campus restaurant, which are both open to the public.

“In the course I’m taking, we don’t really have [academic] subjects,” Garcia said. “We are pretty much just focused on cooking food and cooking techniques. Every week we would have a different topic. One week we’d focus on, say, breakfast dishes and the next week we’d be doing some desserts.”

At CPIT, one of the kitchens has a viewing gallery that allows visitors to watch students in action. At the time of our visit, the command performance was for curry, with a choice of lamb, chicken, seafood or chickpeas as main ingredient. After cooking, the students, half of whom were international students, brought their curry creations to the teacher for tasting and evaluation. It was like watching a much, much more subdued “Hell’s Kitchen.” We even got to taste some of the students’ work.

All the food from the classes goes to a finishing kitchen and is either sold or given away for free. “If their food is sellable, they pass,” said the teacher. “We want to see how good they are from there on.”

Beth Knowles, international director for business development, pointed out that almost all their students find employment. Some nonfood students take the barista course so they can work part-time in coffee shops.

CPIT also has a reception and a hotel suite for front office and housekeeping training. While half the students are working in the room, the other half are out in the viewing gallery watching, according to Tony Kessler, academic manager for the hospitality program. Hospitality students also get trained at the café and the restaurant.

Because he finished secondary school in New Zealand, Garcia didn’t have to take any English language course to be accepted at CPIT.

“Here, once you get to

Year 11, you get to choose subjects that will help you get into whatever course you want to take after high school,” he said. “This gives you an idea what work you’ll be doing in your tertiary studies.”

Programming a dream for progress

JOANNA Rubi is in New Zealand on a student visa. Her parents, who have work permits, hope to be permanent residents soon.

The number of Pinoys who are in New Zealand for education grew significantly in 2014 and continues to grow. According to ENZ reports based on Immigration New Zealand statistics, first-time student visa applications from the Philippines were up 45 percent in May, with most students applying to study at private training establishments.

On the basis of the International Monetary Fund’s annual growth projection for Asean, which is between 5 and 6 percent from 2013 to 2017, ENZ is looking to double the number of their students from the region by the end of 2017.

And why not when the timing is ideal? New Zealand is knocking on the doors of its Asean neighbors just as the middle class across the region—growing in size and income—is shopping for schools where their children can safely learn English, acquire employable skills or pursue research “as a passport to rewarding jobs and global citizenship.”

At Victoria, one of the eight government-funded universities in New Zealand, there are 3,000 international students from over 100 countries, the Asean included.

Rubi joined the university’s international community early this year. Her dean at St. Catherine’s College, a Catholic school founded by the Sisters of Mercy in Wellington, had urged her to apply for a Victoria scholarship on her last year in high school. She did and she got it.

Victoria has 21,000 students, seven faculties (Architecture and Design, Education, Engineering, Humanities and Social Sciences, Science, Law and Graduate Research), and two schools (Business and Music) on four campuses, according to its 2015 prospectus.

While it is highly respected for its strong research portfolio (70 percent of the research undertaken by its faculty members is reportedly at the topmost level), it has also ranked first in 17 of the 36 subject areas it offers, among them, Computer Science, which is Rubi’s major. In an undergraduate degree like Rubi’s, students learn from both lectures and tutorials.

Computer Science is interesting, according to Rubi, because it balances one’s ability to think creatively with one’s ability to think logically.

“Programming is a challenge but it’s fun,” she said. “I had no prior knowledge of coding before coming to Victoria.”

She said she was happy to be studying in New Zealand because the opportunity for learning about programming in the Philippines was comparatively limited.

The Bachelor of Science degree, major in Computer Science, is a three-year program at Victoria. If Rubi adds one more year of study, she can obtain her Bachelor of Science with Honors, a professional degree where she can specialize in Software Engineering.

“My dream is to create software that can help a Third World country like the Philippines,” Rubi said. “I didn’t really recognize how marginalized the condition of many Filipinos was when we were there because I was young. I didn’t understand what was so wrong. But when I got here, my eyes were opened. Living here made me realize how Filipinos are being deprived of the possibilities for a better life. I truly believe the Philippines has a potential to be a powerful Asean country.”

MANAGERS Roger Armstrong and Matthew Eglinton by Victoria’s place of honor for alumnus Alan MacDiarmid, Nobel prize winner for chemistry

To pursue her dream, she would like to get into the master’s degree program at Victoria. Her worry is that her scholarship is for one year only.

“I don’t know if it will continue if I get the grades,” she said.

Like the other Asian students we met, she is awed by the beauty of New Zealand. “It is”—she groped for the precise word—“serene.” But what she likes best about life in Kiwiland are the diversity and the equality in its society. “There’s real democracy here,” she said.

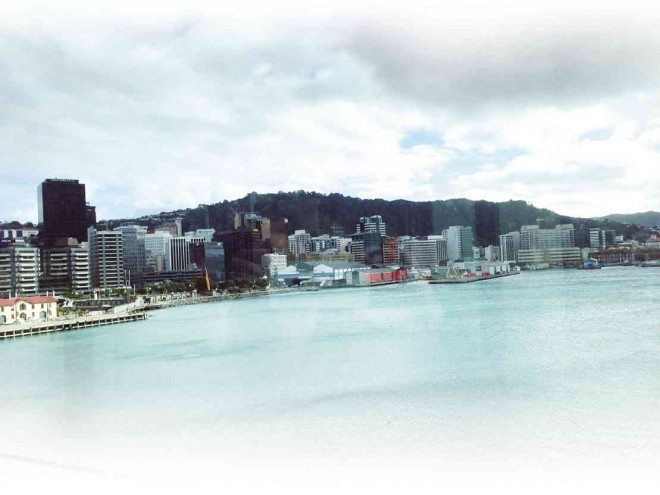

As for the capital city of Wellington, “I love that it’s compact and it’s quiet.”

Rubi had initially wanted to study in the United States, a predisposition that seems to be in the Filipino DNA. But then her parents found work in New Zealand and she received her scholarship. The opportunity to “think new,” as the ENZ catchphrase puts it, was too good to pass up.

So, forget Hollywood.

“Exactly,” she agreed with a wide smile. “Think New Zealand.”

E-mail cbformoso@inquirer.com.ph.