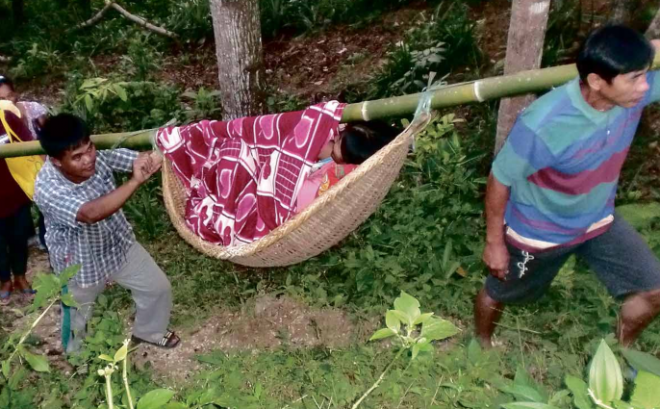

AMBULANSYANG DE PAA (Ambulance on Foot) takes patients across mountains, rivers and rugged terrain to the nearest health facility. PHOTO COURTESY OF ZUELLIG FAMILY FOUNDATION

The graduates couldn’t have been more different from each other: an engineer, a funeral service provider, a seminarian, a teacher, a US postal worker, a policeman, a lawyer and two doctors.

What binds them together— aside from being mayors of poor, mostly upland towns in the provinces of Ilocos Sur, Pangasinan and La Union—is their commitment to public health.

Along with their health officers, these local chief executives were recently recognized for completing the Municipal Leadership and Governance Program (MLGP) of the Department of Health (DOH) and the Zuellig Family Foundation (ZFF).

The graduates proved that even the most disadvantaged barrio or sitio can meet the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) if their leaders are truly committed.

The MDGs are eight time-bound targets drafted by the United Nations in 2000 to reduce extreme poverty in the world. Three of the goals—reduce child mortality; improve maternal health; combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases—are health-related.

The conditions that gave rise to the MDGs are nothing new to the mayor-graduates. Several of them recalled personal struggles with health-related concerns worsened by the geographical isolation of their areas.

“We know now that even a fourth-class municipality can render first-class service to its constituents,” said Mayor Divina Velasco of San Gabriel, La Union.

Velasco’s mother used to be the public health nurse in San Gabriel, a mountainous area with an 85-percent indigenous population.

Town’s burden

With no doctor nor midwife assigned to the place, Velasco said she felt early on how difficult the job was for her mother and what a burden it was for the town to depend on only one individual for their health needs.

“I told myself, I will be the first doctor of our town,” she recalled thinking.

After passing the board exam, Velasco returned to San Gabriel and served as its municipal health officer for 16 years before being elected mayor.

Others might think her post lowly, she said. “They say I should be in Manila specializing in a prestigious hospital, or in the US, like my sisters, but the desire to serve in my own town was intense,” Velasco said.

While Velasco credited her mother for her career choice, Gregorio del Pilar, Ilocos Sur, Mayor Luz Villalobos cited a child lost at birth for hers.

Like many rural women, Villalobos was used to the idea of giving birth at home.

Home-based deliveries, often unassisted by health professionals, are frequent causes of maternal and infant deaths. But in places like Gregorio del Pilar, where there was no nurse, no doctor, no birthing facility and no hospital, home-based deliveries are the only option for mothers.

“But as a leader, I realized I’m responsible for starting change,” Villalobos said. “My constituents look to me to improve their situation.”

Having finished only elementary grade—her father had leprosy and could not send her to school—Villalobos was hesitant to join the MLGP. But when she learned that the mayors of neighboring towns were joining, she was encouraged to join as well.

The MLGP corrected her wrong, but well-intentioned, ideas about making do with whatever resources were at hand.

Formalin for wounds

“We own a funeral parlor so we had a lot of Formalin. I used to give that to farmers with wounds on their feet because we had no other medicine. That’s how poor we are,” the mayor said.

A strong disinfectant, Formalin, however, has some side effects and is not suitable for treating wounds.

Sugpon, another geographically isolated and disadvantaged area in Ilocos Sur, has no hospital. On rainy days, the town can be reached only by boat on the Amburayan River.

To deliver health services, Sugpon’s leaders, many of them belonging to the Bago-Kankanaey tribe, had to be extra creative.

They put in place the Ambulansyang de Paa—a group of men who take turns carrying sick and pregnant townsfolk on a makeshift bed to the nearest health facility. Usually, this makeshift ambulance takes hours of walking.

Hitting on a more permanent solution, the municipal government allocated P700,000 to build Bahay ni Nanay, a halfway house located near the birthing center, where pregnant women can stay while awaiting their delivery date, so they no longer have to travel from far-flung villages where transport is not available.

Quirino, Ilocos Sur, Mayor Clifford Patil-ao, an engineer, knows only too well the risks of living in the mountains with no access to any means of transport.

Carried in blanket

Sickly as a child, he recalled being carried in a blanket by neighbors so that he and his parents could cross a river and ride a rented jeep to Bessang Pass Memorial Hospital in Cervantes, Ilocos Sur.

He was lucky because he survived. Many others don’t make it.

“I’ve seen pregnant women who, after the midwife had given up on them, would be carried by the townsfolk in the middle of the night across the mountains for three hours to reach the nearest hospital. Some babies die in the womb; some are born on the way,” Patil-ao said.

When he had his own family, health again became a personal issue: His eldest child was born with two holes in the heart. Patil-ao moved his family to Bauang, La Union, so they could be closer to doctors.

“One day, my child’s heartbeat just stopped, and we had to rush him to the hospital. The doctors were able to save him, but I thought: If we had been in Quirino, our child probably would have died,” Patil-ao said.

Quirino is the farthest and most isolated of Ilocos Sur’s 14 upland municipalities. It has a population of around 9,300.

Burdened by the thought of his townsfolk suffering because they lacked access to health services, Patil-ao returned to his hometown and won mayor in 2007.

Again, he experienced life like most of his constituents did, especially when he figured twice in life-threatening accidents. Once, he fell from the roof of a school he was inspecting; another time, he was thrown off a motorcycle. In both times, he could not be taken to the hospital until a day later because there was no ambulance.

Patil-ao knew then that he had to make health a priority.

Today, Quirino has a doctor, a community hospital, two ambulances, and a health center that is open 24/7 and accredited by the Philippine Health Insurance Corp. (PhilHealth).

With such firsthand experiences among the mayors and MLGP graduates themselves, it’s no surprise that the World Health Organization (WHO) rated the country’s health conditions poor.

The country was among the 189 UN member states that signed the UN Millennium Declaration and committed to meet the MDGs by 2015. In 2013, the DOH adopted the ZFF’s Health Change Model and began interventions in 609 priority areas identified by the National Anti-Poverty Commission.

Mayors and municipal health officers were coached on leadership and service delivery using a one-year, two-module leadership program, and were expected to improve health indicators in their areas.

Roadmap to health

Under the program, local government units (LGUs) used a roadmap with the WHO’s six building blocks of health: health leadership and governance, health financing, health human resource, health information system, access to medicine and technology, and health service delivery.

Using this roadmap, the LGUs reviewed their health indicators to check what problems needed to be addressed.

“What we’ve seen is a deepened accountability among the leaders because of the MLGP. It’s no longer just words. They are now accountable for what they’ve committed to do… to improve the health of their constituencies,” said Dr. Myrna Cabotaje, DOH Region 1 director.

The mayors and health officers of Ilocos Sur municipalities San Ildefonso, Sugpon, Quirino, Alilem, Gregorio del Pilar and Candon; San Gabriel in La Union; and Basista and Laoac in Pangasinan were among the first batch of local officials to complete the MLGP. They each received P200,000 from DOH Region 1 office to help with their operating expenses.

As of June 26, the nine MLGP graduates have reported zero maternal and infant deaths in their areas, meeting MDGs 4 and 5. Most of the mayors also met the target for reducing malnutrition among the under-5s, as well as trimming the number of malaria cases.

In his speech before the graduates, Dr. Eric Tayag, director of the DOH’s Bureau of Local Health Systems Development, urged the mayors not to go back “to the old ways.”

“What you have accomplished is only the beginning. Your success is a step in the right direction,” said the guest speaker at the June 26 graduation ceremony in La Union.

“You have to continue tracking your programs. You also have to be proud. Announce what you have accomplished; create a buzz. You have to celebrate that this is important to everyone,” Tayag said.

Central Mindanao, Davao and Caraga will have the next batch of MLGP graduates this month.